The “Arts of Resistance” exhibit at the Museum of Anthropology was quite a fascinating exhibit, showcasing the ubiquity of oppression in Central America which ranged from native Aztec Tlatoani to Spanish conquistadors and then neo-colonial corporations 1. Of course, the general theme of oppression was intertwined with the theme of resistance against it ranging from the revival of native art to satire of Christianity and protests against GMOs.

Protests against GMOs. That strikes a chord, but in a wrong way. The exhibit in question, which is called “Defence of Maize”, portrays transgenic maize in a negative light by claiming its lower prices are “negatively affecting the Indigenous and locally grown maize market.” but this exhibits is disturbing on economic, scientific and ethical levels. It advocates a violent, unethical and uncompromising response to the issue at hand without consideration to the poverty stricken in Mexico and highlights how resistance is not always a positive nor beneficial action.

Economics

Economically speaking, a rejection of GMO maize would have a negative affect on the economic conditions within the country, leading to an increase in overall poverty levels and lack of competitiveness against foreign imports. The argument that native farmings communities will be hurt by the introduction of GMO maize is valid to a certain extent, but it can be easily rebutted through two means, the utilitarian perspective and the false dilemma, also known as the fallacy of only having binary choices.

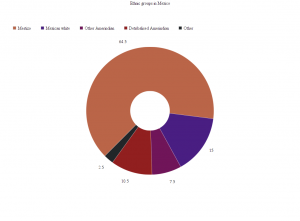

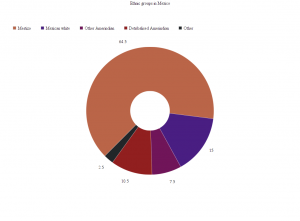

OECD Secretary-general Ángel Gurría estimated that “7 of every 10 Mexicans are living in poverty or vulnerability“2. The introduction of GMO maize can alleviate this problem by making the price of maize more affordable through increased crop yield and higher resistance to insects. Assuming that we adhere to the utilitarianism principle that “the greatest happiness of the greatest number should be the guiding principle of conduct.” we can easily see how that the benefits of GMOs greatly outweighs the costs. According to the CIA Factbook 3, only 13.4 percent of the Mexican workforce is employed in the agricultural sector while only 17.5 percent of the Mexican population is Amerindian, according to Encyclopaedia Brittanica 4. This means that an extremely small portion of indigenous farmers would actually be harmed by the introduction of GMO maize in comparison to the large amount of Mexicans in poverty that would be benefited by the lower price of food.

Remember, regardless whether Mexican or native, human lives are still human lives

Regarding the false dilemma? The exhibit argues any solution to the introduction of GMOs would be binary, either they [The natives] win or they lose. This is shown pretty clearly by the native woman holding up a rifle against cowering scientists, an ethical atrocity that we will go more into depth later on. The absurdity of this idea is shown by the fact that there are plenty of ways to solve this issue without resorting to such extreme means.

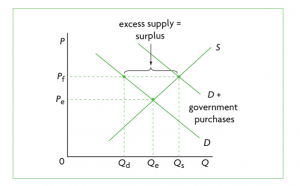

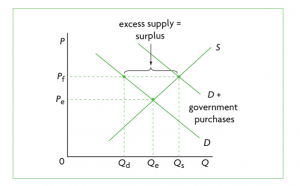

As native farmers make up a minority of the population, the Mexican government can easily offer subsidies to native farmers that plant traditional maize without too much increase in fiscal spending. The government can also give quotas to farmers or set price floors that stabilise their income 5. This will protect them against low cost competition, regardless from GMO maize or foreign importers as their maize will always be bought. Honestly, it’s ridiculous to suggest the introduction of GMO maize will spell the end for indigenous communities.

It can even be argued that not introducing GMO maize will actually spell the end for indigenous communities as the rest of the world will still adopt GMO maize. For one, the United States has already done so extensively for corn and soybeans and the Chinese are following close behind. This means that the prices around the world for maize will fall as more and more countries adopt GMOs, rendering traditional maize in Mexico obsolete unless the government start placings tariffs on foreign crops. Let’s not go into details regarding how disastrous and what sort of trade wars that this sort of action will entail.

Please don’t tell me how to explain this, IB Econ was a long time ago

Scientific

From a scientific perspective, the second crux of this argument primarily deals with two sub-arguments, the benefits of GMOs, and the fact that the entire “tradition” argument is extremely debatable and a weak point to boot.

So the exhibits brings up a few points regarding GMOs, which are in my opinion its only valid ones. The curator calls the effects of GMOs “Very damaging” and that it “Makes the ground un-arable” at 1:41 in her introduction of the exhibit 6. Here’s statistics for GMOs for another country: 88 percent of the corn in the United States is genetically modified along with 93 percent of the soybeans according to the Department of Agriculture 9. Unless the curator’s definition of “very damaging” means obesity, there isn’t currently a massive health crisis in the United States because of those GMOs.

I’ll admit that this is the weakest portion of my argument because I do not take biology nor do I have any advanced knowledge regarding GMOs. An empirical argument based on GMOs in the United States having no visible negative effective is no where as strong as a biological one, but I believe that it is sufficient to prove that most GMOs most likely don’t have the “very damaging” effect that is being claimed, a claim that is supported by the New York Times where 90 percent of scientists believe it to be safe 8.

The un-arable argument is really weak because it partially contradicts the previous argument. One of the major reasons that soil is rendered un-arable is due to too many nutrients being absorbed by the plants (Aka. Law of conservation of mass, those nutrients still have to go something), this is actually a common problem which appeared prominently on the plantations of the South where excessive monocropping of cotton rendered the soil un-arable. This isn’t a new phenomenon and can be easily be solved by crop rotation, which has the increased benefit of expanding the types of crops planting which actually increases financial stability as farmers have back-up in case prices for a particular crop collapses.

Lastly, what you see below was the ancestor of maize. Along with many other cultivated plants, they were slowly modified over long periods of time through the process of breeding to gain positive traits until they became the maize we know today. This process is known as genetic modification. Of course, selective inbreeding is not exactly the same as transgenic GMOs, but the goal is the same. To weed out negative traits and instil positive traits that will make farming and the final product both easier and better. It is only the methodology that has changed.

The tradition argument is not completely without merit, indeed it was the Amerindians that modified ancient Maize, but a rejection of GMOs based on tradition is problematic in that it is basically rejecting a process that has the same goals and ideas of the original traditions in the first place. The argument that improvements in technology that lower costs will hurt traditional industries is easily exploitable to be used in basically any technological setting. Thus the entire thing feels just Luddite in nature and threatens to stagnate scientific development in Mexico as a whole merely for the benefit of the few.

Ethical

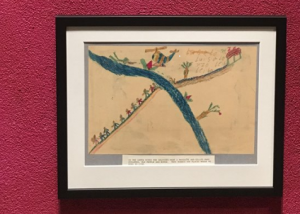

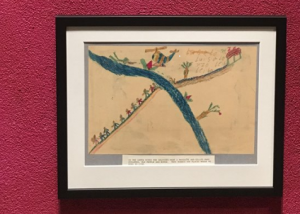

There’s a picture below of the “Defence of Maize” exhibit 9, and below that is a children’s picture of American built attack helicopters attacking refugees. The first exhibit shows a violent response to scientists that are trying to cultivate better and more efficient maize that will benefit the poor. The violent response is largely in response to the threat that this cheap maize poses to the personal interests of the native farmers. There is no recourse other than violence because there is no alternative. If they refuse to accept the new kind of maize [Since they refuse to accept alternatives] , they will lose their livelihoods and will forever be forced to rely on social welfare.

The second exhibit below that shows a violent response to fleeing migrants from a repressive regime who were just seeking asylum and a better life. This violent response is largely in response to the threat that the natives, which made up most of the rebel forces, posed to the government during the civil war. There is no recourse to violence because there was no alternative. Ok, that’s enough. I think I’ve made my point and there’s no need to make up arguments for genocides.

It is true that those two events are on vastly different scales, but the mindset behind them is essentially the same: violence is the solution to threats to your personal interests and all alternatives are non existent. Note that the people being threatened with bodily violence in the first exhibit are civilian scientists and not business executives which would be also bad, but not to the same extent.

This exhibit is basically an atrocity in action. You do not point guns at scientists to get across a point during a discussion, you point guns because you are threatening or actually about to kill someone. There’s honestly no other way to interpret this other than that. This exhibit is morally repugnant in the extreme for suggesting violence against innocents in the defence of “personal interests”

Conclusion

Indeed, it is important to think about the native and indigenous farming communities across Mexico that will be unable to compete against the GMOs, but in a changing world where 78.84 percent of Mexico now lives in urban areas, it is also essential to consider that a much larger amount of people will be negatively impacted if GMOs were to be withdrawn or even banned from Mexico. There are plenty of ways to deal with the issue of an disadvantaged native community ranging from quotas of native crops to just overall subsidisation. This is just under the assumption that the native communities stick with their original varieties of maize while they could just as easily switch over to the new kind and increase their own crop yield as well.

In a way, the distinction of oppressor and oppressed has become increasingly blurry the more you consider this issue. The exhibit “Defence of Maize” gives a biased response to the use of GMOs, showing the negative aspects of GMOs in addition to ignoring the benefits it brings while excluding the idea of any alternatives and responding to the entire issue with the threat of violence.

So let me ask you this as a closing statement.

Is there a certain point where resistance merely becomes oppression of a different sort?

1.“Arts of Resistance.” Museum of Anthropology at UBC, MOA, moa.ubc.ca/exhibition/arts-of-resistance/.

2.“Mexique – OCDE, Global and Mexico Economic Outlook 2018.” Estadísticas – OECD, OECD, www.oecd.org/fr/mexique/global-and-mexico-economic-outlook-2018.htm.

3.“The World Factbook: MEXICO.” Central Intelligence Agency, Central Intelligence Agency, 26 Sept. 2018, www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mx.html.

4. Cline, Howard F., and Angel Palerm. “Mexico.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 28 Sept. 2018, www.britannica.com/place/Mexico/Ethnic-groups.

5. Holroyd, Stephen. IB Economics. Oxford Study Courses, 2004.

6. “#5 The Defence of Maize.” YouTube, YouTube, 17 Sept. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=5N96FK4CHiM.

7.“Biotechnology FAQs.” USDA, www.usda.gov/topics/biotechnology/biotechnology-frequently-asked-questions-faqs.

8. Brody, Jane E. “Are G.M.O. Foods Safe?” The New York Times, The New York Times, 23 Apr. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/04/23/well/eat/are-gmo-foods-safe.html.

9. “Arts of Resistance.” Museum of Anthropology at UBC, MOA, moa.ubc.ca/exhibition/arts-of-resistance/.