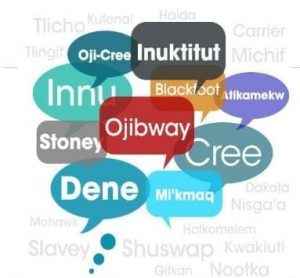

I have always been interested in languages having been exposed to them all my life. My grandparents and parents went between French and English, my Uncle Gary, who rudely interrupted 400 years of French-Canadian inbreeding, spoke Ukrainian at home and it was common when spending summer with my father’s parents on their farm in Manitoba to hear friends and neighbours slip off into Michif on occasion. (I shouldn’t be too hard on my uncle as truthfully, our inbreeding had been interrupted a number of times earlier on as our family also identifies as Metis)

As a kid growing up in a rough area of Winnipeg (Slurpee and murder capital of the world at the time – Was there a connection?), I was also exposed to the languages of the big immigrant communities beginning to shape the city at that time, Vietnamese and Tagalog, along with the Cree and Ojibwe of many of my neighbours. I wouldn’t wish the poverty and violence I grew up with on anyone but living in that community gave me an exposure and curiosity about how other people lived and spoke that as lasted until this day and an exposure not likely available anywhere else in the 1970s Manitoba of my childhood.

When thinking back to my childhood and reflecting on the place of languages in the world today, especially the smaller and therefore, almost always, shrinking ones, my mind turns to the way technology can facilitate the preservation and development of languages that are either so small there is little support for them or where, as in the case of immigration, any significant educational resources or hardcopy texts are far away.

(picture from the amazing children’s kabuki festival in Komatsu, Japan)

(picture from the amazing children’s kabuki festival in Komatsu, Japan)

Even as recently as when I began teaching Japanese a few years ago, I would prize any Japanese book or manga I could find as you didn’t get many chances to pick them up even in a diverse city like Vancouver. With the internet and digital resources, I can now open up any number of resources. My wife and I, regularly watch Japanese TV and as a theatre buff I can access an app that allows me to watch Japanese theatre on demand (I am a huge shin kabuki – New Kabuki – fan). On top of it, my three-year old daughter can access educational programs in English, French and Japanese and we can source worksheets and supporting materials for all three languages as well. In fact, most streaming services let you to toggle between a number of global languages when watching much of their content. For major global languages, the on-line world has become a rich source of support regardless of where you actually live.

In terms of this blog, my focus is on those smaller (but not lesser) languages and the impact that digital technology can have in supporting them. There are a few ways that come to mind and that are discussed in the literature.

Sample of Ojibwe syllabary

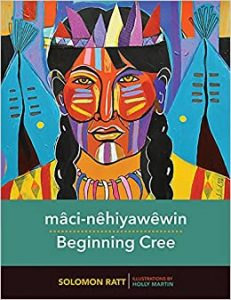

- Character Sets – While not all languages initially had written forms, most do now (thank you missionaries?). This means that there are ways to record, retain and communicate in these languages using characters. If we were still bound by print conventions, this is a difficult challenge to overcome. If you wanted to establish a textbook or other resource in the target language, you would have to set up a printing press or word processor to accommodate the language and then print up whatever resources you need. If the language has only a few thousand or hundred speakers, the work may not be worth the effort and print runs of a few hundred might be quite costly. It would be naïve to say it is easy, but it is more possible to do this in a digital format. Digital character sets have already been designed now even for languages with few speakers (but not all and that can lead to other challenges with languages with an exclusively oral tradition – Ebadi, 2018) and by using a digital format, even an interface can be designed to make writing in the language fairly accessible (Li, Brar & Roihan, 2021, Williams, 2018).

- Resources – As mentioned above, the likelihood of producing many hardcopy resources of smaller language resources is limited by the cost of small print runs. Printing out work sheets might be fine but how do you justify the equivalent of novels or longer technical documents. By focusing on developing on-line or digital resources, as long as there are devices available (sometimes a big ‘if` but less and less so (Li, Brar & Roihan, 2021; Williams, 2018)), people can access these resources without ever having to go through the arduous process of having a printed copy made. There is also the benefit of texts accumulating over time. An on-line library could, essentially, be an ever expanding one; whereas, equipping each speaker of a language with hardcopies of each new book or other resource that comes out seems a bit unlikely and wasteful.

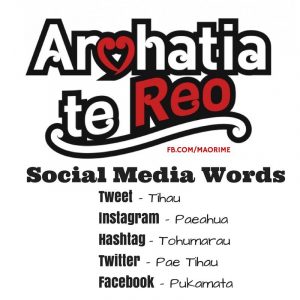

Maori Social Media terms

- Multimedia – The other advantage of digital and on-line resources is that they allow for the preservation and dissemination of languages using a range of media. Films, TV shows, tutorials and all manner of audio or video material can be made available in a way that would be hard to duplicate in another manner. There is also the possibility of using social media (Ibaraki, 2018) and hosting on-line discussions and classes. With smaller languages, especially ones whose communities have been widely dispersed, this seems like one of the best ways to help sustain their communities as well as their languages (Williams, 2018).

Digital and on-line materials are not, by any length of the imagination, a panacea for languages that are shrinking but they do hold a tremendous amount of promise. One of the challenges besides the availability of technology, would be the access to cross-over expertise in those languages as well as the technological skills to make the best use of digital resources. In trying to learn michif, I have found resources but most are at the amateurish enthusiasm level or are not well maintained (Case in point: http://www.louisrielinstitute.ca/146-michif-language-lessons-now-available-online.php whose videos run on Flash which no longer exists…). I am, of course, unbelievably thankful for the resources that do exist but by virtue of these languages having few speakers, the support is, correspondingly thin for the most part.

Another caveat would be that the on-line world is leading to the strengthening of the power of the dominant global languages and, therefore, adding to the pressure on smaller languages (Williams, 2018).

Regardless, it does seem like the digital world could offer a tremendous support to language learners of all types but might be particularly useful in the urgent matter or preserving and propagating endangered languages.

References

I appreciate the personal and reflective nature of your post. You engage your reader and leave them with many ideas to consider. Interesting that technology can be used to help support and preserve at-risk languages while at the same time strengthening the power of dominant global languages. Your work made me reflect on how I might incorporate tools and resources such as https://www.firstvoices.com/ into my SLLC programs.

I appreciate how you connected your personal experiences with languages and technology. It also made me think about the many ELL students in my class, and ways that I can help them learn English while also preserving their own language.

Thanks for the response, Saliha. One of the most disappointing things I found when I arrived in Vancouver was realizing how much we are throwing away as a country when we essential ignore the first languages of our ELL students. The on-line world can definitely bridge that gap.

Mind you, I have never understood why we don’t have classes available to support students from other cultures, especially with the big languages entering our system. Surely, Vancouver or the districts of greater Vancouver would have enough students and promise of future ones to launch literacy support programs for languages like: Mandarin, Cantonese, Tagalog, Vietnamese and Punjabi (These are big ones in my school).

We aren’t robbing children of fluency in English by supporting their first languages. In my experience, strong literacy in a first language supports literacy development in other languages not to mention the power it gives to the student in terms of self-identity.

Hi Guy,

I somehow missed this post earlier, but I found it inspiring. The Squamish Nation has launched an digital education initiative with the goal to revive their language. It includes a digital map of the Howe Sound area. The user can “click” on an area and it will give audio with the correct Squamish pronunciation and myths or stories related to the region. Check it out: http://squamishatlas.com/

The language and cultural revival initiative has been put together by this group:

https://www.kwiawtstelmexw.com/

Thanks, Anna

Wow! Thanks, Anna. Those are both great sites. Thank you for introducing them.

I find with my Japanese students (I teach Japanese and English), as they are studying a major language, the resources are unbelievable. I don’t think it is too much to hope that many of the world’s smaller and shrinking languages might get a bigger share of that on-line support.