My home library is unique in that it is an Education branch in a large post-secondary Library System. I will refer to it here as an”Education Library” or my “Home Library” without referring to the specific location or name. Please note that the comments made in this blog post are not intended as a criticism of the individual library, library system or the capable and hard working librarians and staff of my ‘home’ library.

“In light of (these) technological advances, is a reference collection still justified in a library or is it merely a relic of the past?” (Epp & Hochheim, 2014, p.59)

The above question is not new or unique. I found multiple older articles asking similar questions with respect to post-secondary academic and curriculum libraries and while Epp & Hochheim’s 2014 paper, “Increasing Access to the Reference Collection”, is related specifically to medical libraries, it draws conclusions relevant to other library contexts including, perhaps, my ‘home library’, an Education Library in the Faculty of Education at a Canadian post-secondary institution. This library, like the medical libraries noted in the study, has integrated the reference collection throughout the stacks on both floors of the library rather than housing it in a physically separate reference section. According to the study, this is a more effective arrangement and, in the medical library context where “Healthcare professionals rely heavily on point-of-care tools, which are typically available as downloadable mobile apps” (p. 60) is valid. In such contexts, it seems there is little doubt that a physical reference collection is becoming or has become redundant. I believe that while there are some similarities, the context of a library in a Faculty of Education serving educators (including pre-service and in-service teachers) has unique needs.

In the FoE context, a large part of the mandate of the library is to serve the needs of the 750+ students (annually) in the Bachelor of Education Program (BEd). These students are Teacher Candidates (TCs) who will be embarking on practicums during their 11-month intensive program come from varied academic backgrounds and have needs that are vastly different from typical university students. TCs benefit from developing an understanding of the library not only in terms of how they use it as students but also in terms of how they will use it as teachers with their own students.

In my discussion with the reference librarians, I understand that the decision to redistribute the reference collection was made several years ago in response to the same perceived declining use of the materials and the time and resources needed to effectively manage this section as noted in Epp and Hochheim (2015). The intent was to allow for student borrowing of these items as part of the circulating stacks. An error made at the time of integration was the lack of weeding. Francis (2012), notes that “As the use of the reference collection changes, it is important for the collection to match that use. A bloated reference collection focused on the needs of patrons from 20 years ago offers little service to the current patrons.” In my ‘home library’, this bloat has resulted in a large number of dated resources taking up considerable space in their respective content and subject areas of the stacks leading to less effective access and use. In addition, little time or funds have been spent to purchase new physical reference materials – in part because there is no visible section highlighting the need for newer resources. I question the value of having any of these resources integrated if they are not being regularly evaluated and weeded.

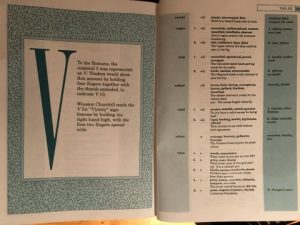

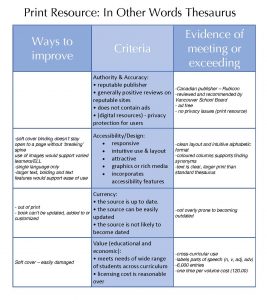

Note: As part of an informal survey of a set of reference resources for a previous assignment, I selected 10 dictionaries and thesauri with my only criteria being that some were newer looking and some were older looking. At the circulation desk I found that of the ten items I’d selected, none had been borrowed in the past five years. Given these books are located in the basement in an unidentified section and given the proliferation of effective and up to date online dictionaries and thesauri, I am not surprised by this discovery. Still, were there to be a very carefully curated set of up to date materials (with all others weeded in keeping with Riedling’s 2013 assertions), perhaps these would find wider in-library use and even some limited circulation.

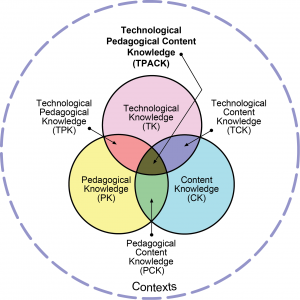

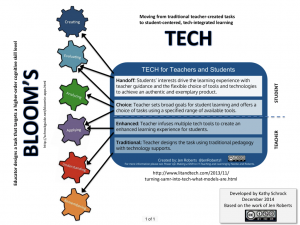

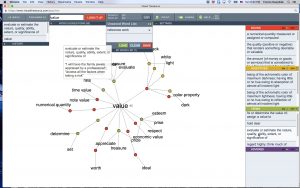

A number of studies suggest that the reference collection, rather than encompassing all reference resources, should be curated such that it contains the reference resources most relevant to the library patrons (Francis, 2012, Nolan, 1991, Pierard & Bordeianu, 2016). In the case of my ‘Home Library’, I suggest that the collection needs to meet the needs of pre-service and in-service teachers and should contain materials to support students as they design learning experiences and unit plans for their teaching. It is during this planning that they frequently come to the library looking for help. For academic needs, these students and our graduate students frequently find what they need through the library’s online collection.

“Exploring a new subject? Starting a research project? We recommend reference resources as the first place to start when you are learning about a topic.” (SFU library home page)

If the above holds true, then easy access to such materials needs to be a priority in a library. In my experience, students (and even teachers) typically do not know how to differentiate between reference and other sources unless such reference materials are clearly identified and/or held in a designated area of the library. Given that most elementary and secondary school libraries have a physical reference collection, and given that part of the purpose of a library in a Faculty of Education is to model for our teacher candidates how they might interact with school library resources and collaborate with a teacher librarian, it is reasonable to model the organization of the library, or at least a section of the library, after that which might be found in a K-12 school.

Stewart Middle Magnet School Library showing interactive, flex learning space, wall-shelf of reference resources. Retrieved from http://renovatedlearning.com/2015/01/28/rethinking-our-library-space/

While I understand the initial decision to put reference materials into circulation, I question whether this required such materials to be integrated physically within the stacks. Could not the foundational idea of a reference collection be reviewed and revised to allow for circulation, while still physically existing in an easily accessible and highlighted space – one that is integrated into a learning commons? Teacher Candidates would benefit from the opportunity to have classes in a ‘school library-like’ setting facilitated by a librarian acting as ‘teacher librarian’.

I envision a space where students can experience what they might encounter in a school library that is embedded in an instructional approach supportive of modeling current pedagogies. Already, in my ‘Home Library’, a young learners and makerspace corner have been initiated. Utilizing an adjacent study area as an “Information Commons” (Pierard & Bordeianu, 2016) with ready access to a carefully selected and curated set of reference materials, digital devices (ideally portable) and flexible seating that invites collaboration, would further bring the library in-line with suggestions in Leading the Learning (Canadian School Libraries, 2018) and other current literature.

A number of studies suggest that the reference collection, rather than encompassing all reference resources, should be curated such that it contains the reference resources most relevant to the library patrons (Francis, 2012, Nolan, 1991, Pierard & Bordeianu, 2016). The Doucette Library at the University of Calgary (Brydges, 2009) deliberately refined its purpose and became a Teaching Resource Library to better meet the needs of pre-service and in-service teachers in recognition that other branches of the University Library system could better meet research needs. This allowed more effective focus and arrangement so that the library houses materials to support students as they design cross-curricular learning experiences and unit plans. It is during this planning that students in our BEd program frequently come to the library looking for help. As mentioned earlier, these resources should be available on limited loan and, further, be organized to support effective selection by teacher candidates who are often unfamiliar with appropriate ‘leveling’ of resources for use with their practicum grade level.

Key Resources for the section based on consultation with an Education Reference Librarian and former Teacher Librarian:

- A selection of current textbooks at various grade levels selected carefully and in consultation with local school districts and faculty/experts in the field.

- A small selection of dictionaries and thesaurus appropriate for primary, intermediate and secondary students.

- A small collection of current and visually appealing Atlas’

- A highly visual Encyclopedia set or two to support young learners and those for whom online reference is less accessible.

- Cross-curricular project handbooks & collections including STEM & Makerspace (ideally, the tools and materials needed could also be housed close by in this flexible learning space)

Putting a Plan in Place (approximately 2 year plan):

Appendix 4 of Leading the Learning (Canadian School Libraries, 2018) can be followed while referencing Appendix 5 during the planning phase to support the effective development and organization of a new and radically different “Reference Resource” section of the library. A summary of key steps drawn from these documents applied to this project:

- Preparation Phase: Free up space by reviewing what is not being used, remove from the facility and utilize wall space where possible. Systematically weed, weed, weed (as echoed in Riedling, 2013 p. 23. (12 months)

- Consultation phase: Highlight the newly available space, use inviting signage to engage and invite feedback from students and faculty on a physical graffiti wall and a virtual wall: “What do you want to see here? What do you need?” (3 months)

- Planning and Funding: Draw plans, seek and find funding (always a struggle but worth the time – there are facilities improvement funds available through the University to improve student-forward learning spaces). (6 – 12 months)

- Carry out plans. (3 months in summer term to avoid disruption)

In Conclusion:

For the purposes of this paper, I reviewed several libraries in Faculties of Education across Canada and believe that the physical layout and collections arrangement at the Education Library at Queen’s University is supportive of better meeting the needs of BEd students.

Let’s imagine a whiteboard next to a low shelf of reference resources…(Queen’s University Library Teaching Corner Retrieved from: https://library.queensu.ca/sites/default/files/styles/location_slider_full/public/images/locations/education-teaching-corner.jpg?itok=7WWHHbQO

Further, the direction taken by the Doucette Library at the University of Calgary (Brydges, 2009) to refine its purpose and become a teaching resource library supports my assertion that changes are needed in my ‘Home Library’ including the development of a small, focused and well-curated selection of reference materials. These materials should be available for limited loan periods and be housed in a space conducive to collaboration and instruction to support pre-service and in-service teachers in finding and utilizing these resources and, in turn, provide modeling as to how they might use such a section with students in their own school library.

My ‘Home Library’ may be trying to meet the needs of too varied an audience. Students might be better served by other libraries in the wider University Library system with the Education Library focusing on pre-service and in-service teachers for their BEd program, Masters studies and professional development as a Teaching Resource Library. While there are space limitations in my ‘Home Library’, I see the potential to create a more efficient Learning Commons and Teaching Resource library. Such a transformation would require a longer term, well-resourced and carefully conceived plan of action than suggested in this proposal. It would involve a large investment of time to develop and carry out a comprehensive weeding strategy and input from the wider community of students, academics and the public. Who knows, such a plan may even be in the works!

References:

Brydges, B. (2009). A century of library support for Teacher Education in Calgary, Education Libraries, 32 (1). Retrieved from: https://prism.ucalgary.ca/bitstream/handle/1880/108903/266-556-1-SM.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Canadian School Libraries (CSL), (2018). “Leading learning: Standards of practice for school library learning commons in Canada.” Retrieved from: http://llsop.canadianschoollibraries.ca

Epp, C., & Hochheim, L. (2015). Restricted: Increasing access to the reference collection. Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association, 36 (2). Retrieved from: https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/jchla/index.php/jchla/article/view/24394/18722

Francis, M. (2012). Weeding the reference collection: A case study of collection management, The Reference Librarian, 53(2), 219-234, DOI: 10.1080/02763877.2011.619458

Nolan, C. W. (1999). Managing the reference collection, Chicago: American Library Association.

Pierard, C., Bordeianu, S. (2016). “Learning commons reference collections in ARL libraries”, Reference Services Review, 44 (3), 411-430. Retrieved from: https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.1108/RSR-02-2016-0014

Riedling, A., Shake, L, Houston, C. (2013). Reference skills for the school librarian: Tools and tips, (Third Edition). Santa Barbara California: Linworth.

Simon Fraser University Home Page, Retrieved from https://www.lib.sfu.ca/find/other-materials/reference-sources/what-are-reference-books on Nov. 25, 2018

Follow

Follow