Recently I had a heated discussion with a retired school librarian who firmly believes that the need for a reference section and the need for physical reference materials was a thing of the past. She was frustrated that my understandings from this course were leading me to hold reference materials in reverence! She was quite adamant that library resources and space could be more effectively allocated. I found myself smiling when I realized that, prior to the readings and discussions in Module 3, I would have blindly agreed. Having completed the Reference Materials module, however, my own initial beliefs and bias have shifted.

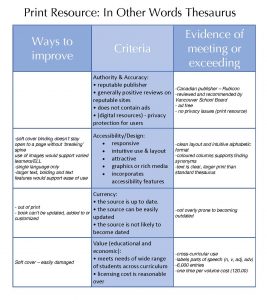

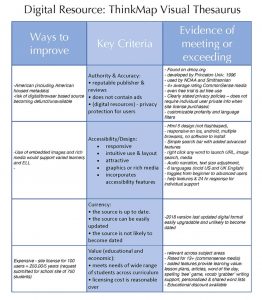

I made a sweeping statement in an earlier assignment about the primacy of online reference resources over print resources from a space, cost and environmental perspective. Thankfully, Florian challenged my statement and got me thinking further about the role of reference materials and how to best allocate scarce resources (space, time and money). In the end, I found myself arguing ‘for’ hard copy reference materials and a physical space that highlights and makes these resources accessible.

In this course, we’ve considered the physical library setting, print and digital resources and the role of the teacher librarian. All of these aspects weave together to make the library learning commons what it can be:

“a whole school approach to building a participatory learning community.” (p. 5 Leading Learning).

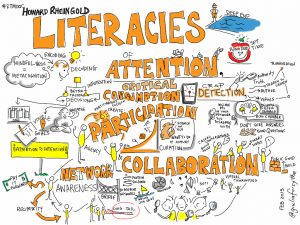

cc image Giulia Forsythe Flickr Stream

I’ve known several librarians who have worked hard and felt like they were swimming upstream as they drastically weeded resources and radically shifted the physical space, moving towards providing makerspace opportunities, increasing access to digital resources and creating an online, virtual presence to support students in conducting inquiries and knowledge construction. Some are fortunate enough to be a part of a supportive and collaborative school culture or are skilled (and supported) enough to help shift the culture. For these lucky TL’s, the hours of work (and working through some resistance) seem to pay off. For those, however, who haven’t seen the shift in student learning or school culture they’d hoped, it can be disappointing or even disillusioning. Their library may be a beautiful, engaging and physically comfortable space, but they just don’t feel like they’re making the difference they’d hoped. Teachers are ‘using’ the library as a separate space where they drop their students during prep time rather than engaging with the librarian in co-planning and co-teaching. Of course, I’ve also been a teacher in schools where I want this kind of support but am disappointed to find the teacher librarian is more focussed on facilitating book exchange, developing a stand along program of library instruction and leaving at 3pm than working together to transform learning opportunities. As mentioned in a post in Module 5, Riedling’s librarian reminds me more of the latter while the Leading Learning librarian is the former. I hope to be the former (but perhaps with a bit of Riedling’s obviously vast knowledge about reference materials ;D).

“Active and knowledgeable involvement in participatory learning is a necessary competence for today’s learners.” (Leading Learning p.19)

Like our learners, librarians need to be involved in participatory culture. A librarian can’t simply ‘build it and hope they come’, but must help lead the change and model a new way of teaching and learning in a school. But how? I’d suggest they might start with engaging the school community in applying a human-centered design thinking approach to moving the library and the school forward during a time of curriculum change. Staying abreast of research and effective pedagogies (such as design thinking) can place the librarian as one who is seen to lead learning in the school. I love this example of teens engaged in tranforming a local library – what an opportunity!

“Regardless of which teachers inhabit and inherit new learning spaces, they will do so differently, according to their own perceived needs and those of their students. A move into a new space can therefore be viewed as a “finished beginning” and a starting point from which adaptations that support successful learning can occur.” (Barrett &Zhang, 2009 in Bradbeer, 2016, p. 76)

As a teacher, I’ve tried to not be ‘binary’ in my views – black and white; yes and no; good and bad – but instead, have tried to inhabit a space between. A friend once told me that I seem to naturally occupy what she referred to as the “Middle Space” in my work and personal relationships. As I read about this space, I realize that this is the space librarians (who are also mentors, leaders and coaches) can benefit from inhabiting. In this space, we’re best able to collaborate and, as a result, innovate and influence learning. As someone working in this middle space, I see the opportunity to both bring my perspectives to any discussion and to learn from the views and ideas of others – something I’ve endeavoured to do in this course, as a teacher with my students and as a colleague.

References:

Bradbeer, C, Working Together in the space-between Pedagogy, Learning Environment and Teacher Collaboration, 2016, 8 pp.75 – 90

Canadian Library Association. “Leading Learning: Standards of Practice for School Library Learning Commons in Canada” (2014) http://llsop.canadianschoollibraries.ca/ (Links to an external site.)Links to an external site.

Riedling, Ann, Reference skills for the school library media specialist: Tools and tips, (Third Edition). Pgs. 99-105. Linworth.

Follow

Follow