This post is written by Professor Jocelyn Stacey.

In the spring of 2019, I was honoured to give one of the keynote addresses at the annual Women in Law event. The address queried what it means to do environmental law well in the age of climate disruption. It emphasized the relevance of environmental law to women in law – both women lawyers and community leaders. This blog post is a modified version of the keynote address. It is written in the style of a food blog. That is, you have to read my lengthy backstory before you get to the recipe. This is the backdrop that shapes my understanding of what it means to me to be a woman in environmental law today.

I do not have a pre-ecological consciousness. I have always been aware of humanity’s existential dependence on the environment. I have always felt a responsibility to protect the environment.

I do, however, remember quite vividly my decision to apply to law school. Russia was in the news, but for reasons completely different than today. Russia had saved the Kyoto Protocol. Russia’s ratification meant that this milestone international agreement on climate change had passed the crucial threshold needed to come into effect.

At the time, I was a research technician for the federal government working on climate science. I know that sounds really impressive (or at least hard). I had the job of collecting sticks in the boreal forest and weighing them. It was important foundational research but was hardly impressive or intellectually demanding. I remember sitting in the lunch room with my colleagues at the office and feeling optimistic that this agreement, which Canada previously ratified in 2002, would generate tangible global action on climate change.

I applied to law school, thinking that that particular moment was when global momentum was shifting from compiling evidence of climate change to implementing – through law—our collective response to this global threat.

Several years later I decided to pursue academia after the Federal Court held that Canada’s Kyoto Protocol Implementation Act was not justiciable. The Court determined that the Act which, on its face, appeared to require the federal government to report on its implementation of international climate commitments, was immune from judicial scrutiny. The Federal Court of Appeal agreed without issuing reasons and the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) denied leave to appeal.

This decision became somewhat of a fixation for me. It challenged what I thought I knew about public law. How could it be that the court could not supervise the executive’s compliance with specific obligations set out in legislation? How could it be that on, one of the most pressing issues of our time, the court had nothing to say? What assumptions about law must a judge cling to when rendering a decision like that? This was a challenge that I just had to resolve. I was sure that, if I could expose untenable assumptions about law that are deeply embedded in the legal system, then I could help shift the legal system toward supporting positive climate action.

Last term I taught Environmental Law as I do almost every year. We started the semester shortly after Tahlequah, a mother and member of the endangered southern resident orca population, ended her unprecedented public mourning of her dead calf. The semester arrived on the heels of a heatwave that killed over 90 people in Quebec. The heatwave featured in a Guardian profile of heat as the next big inequality issue. Midway through the semester, the IPCC released its Special Report on a 1.5°C warming scenario. It reported on the catastrophic impacts around the world that will likely follow from a 2°C rise in global average temperatures, the severe but-less-catastrophic impacts that are likely to follow from a 1.5°C warming scenario, and all the known tools that law and policymakers have at their disposal to prevent these realities from coming to pass. Finally, and shortly before we ended for the term, a report was published documenting the rise of ecological grief amongst Canadians and people around the world. Climate change anxiety, food insecurity, PTSD from climate-related disasters are all on the rise as contributors to mental health issues. This is entirely unsurprising in light of the overwhelming number of concerning environmental trends. This last report I had on my power point slides, ready to discuss with the class, but I could not bear to end the course on a note of despair.

When I read this kind of news of course I feel sad and sometimes angry. But I mostly see a challenge – or many. I see so, so much space for making a positive contribution. I see that Federal Court decision on the Kyoto Protocol Implementation Act replicated across the Canadian legal system. The issues are daunting and pervasive, but so are the possibilities for change.

This brings me to my three observations about what it means to me to do environmental law well in an era of climate change.

- Environmental Law and Courage

I think of doing environmental law as an act of courage. I borrow here from Dr. Kate Marvel a climate scientist with NASA who says about climate change: “we need courage not hope” and “Courage is the resolve to do well without the assurance of a happy ending.”

For years, like many environmental law colleagues, I’ve considered myself an optimist. I’ve thought that it is this optimism that fuels my commitment to environmental law. I’ve thought that, if only I can instill this sense of optimism in my students, they will be empowered to go out into the world and do good work.

I now think that my self-ascribed optimism was mistaken. For one thing, I spend an inordinate amount of time thinking about disasters. This is not a sign of an optimist. I now realize it is not optimism that fuels my commitment. It is possibility. Possibility of change. Possibility of being part of that change.

And so I think Dr Kate Marvel is right. It is not hope, but courage that is the necessary response to daunting environmental reports, inadequate environmental protections and government intransigence. Courage is what makes someone persevere even when the possibility for change seems slight.

- Environmental Law and Feminism

I think of doing environmental law well in an era of climate change as a commitment to intersectional feminism. The impacts of climate change are hugely unequal, with those who have contributed least to greenhouse gas emissions bearing the worst of the consequences. This includes children and future generations, and those who live in conditions of poverty here in Canada and around the world. And as we in Canada are now faced with summer after summer of historic floods, wildfires and heat waves, we should heed the warning from more than 50 years of social science that documents how disasters are not social equalizers. Rather, disasters have social causes that render individuals and groups who are already marginalized – due to gender, race, ability, age and/or economic status – more vulnerable to disaster. The fatalities during the Quebec summer heat wave were people whose identities and lives were at the intersection of age, ability, poverty and gender.

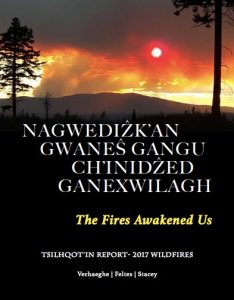

The law is implicated both as a cause and as a potential solution to these issues of inequality. For example, basic features of constitutional law render First Nations communities more vulnerable to disasters – divisions of powers between governments and contested jurisdiction impedes the seamless coordination between levels of government needed to respond to major disasters. At the same time, law can and must adapt and respond to these known challenges. It must require decision-makers to attend to these vulnerabilities when making crucial decisions – whether about environmental disasters or otherwise. Environmental law in an era of climate change must be action-forcing and equality-forcing. And every little contribution counts.

- Women in (Environmental) Law

Finally, doing environmental law well means being surrounded by phenomenal women. If you look behind environmental law cases and environmental news, you will find strong women everywhere. Studies have documented for decades the disproportionate burden of care-giving work borne by women. It seems perfectly consistent that women carry a disproportionate burden of work caring for the environment too. Indeed there are countless women across the country working tirelessly to keep their social and ecological communities safe from environmental harms – climate change related or otherwise.

Because the third and final way in which I think you do environmental law well in the age of climate change is to find one of these women, or someone like them. So… find your:

Martha Kostuch, a late Alberta farm veterinarian who, for decades, worked to ensure that approvals for dam construction and sour gas well development were made with proper attention to the environmental harms of those decisions.

Marilyn Slett, the long-time Chief of the Heiltsuk Nation, currently leading an almost all-female Tribal Council and seeking to enforce the polluter pays principle for the 100,000 Litres of diesel oil that was spilled from a sinking tug boat and that devastated Heiltsuk shorelines.

Maisie Shiell, a Saskatchewan anti-nuclear activist, who sought the right to be heard in public decisions about uranium mining and who was dismissed by the court as a “mere busybody.”

Carleen Thomas or Charlene Aleck, Tsleil Waututh women who have led the Sacred Trust Initiative, exercising Tsleil Waututh jurisdiction over the Burrard Inlet and the harmful impacts on the Inlet and Tsleil Waututh shorelines that would follow from the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion and the increase in tanker traffic.

Ada Lockridge, an Aamjimwaang woman working to protect her community from the toxic air pollutants emitted from the 40% of Canada’s petrochemical industry – 57 polluters – located within 25 km of her community’s reserve.

Alexandra Morton, a fisheries scientist who has, for over a decade, led and won three successive court challenges arguing that governments must take a precautionary approach to open-water aquaculture to protect BC and Canada’s iconic wild salmon populations.

Doing environmental law well means working alongside the resilient women who are everywhere, working tirelessly on life-sustaining issues. It means supporting those women. Not by giving them hope, but by finding possibility. And giving each other courage.