The Crisis of the Fossil-Fuel Mode of Production: Critical Response1

The system of global capitalism is approaching limits to growth. Most clearly poised for transformation is the underlying energetic basis of the economic system, fossil fuels. In this response I will briefly historicize the integral nature of fossil fuels to the contemporary form of capitalism and seek to understand the ways in which capitalism is coping with limits to its energetic basis.

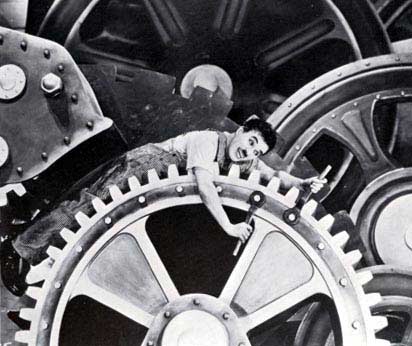

Historically, fossil fuels played a critical role in the spread of capitalist relations. Fossil fuels, particularly oil, are an extremely concentrated source of energy and a geographically mobile source of energy. These flexible properties forever changed capitalism’s productive forces, and its means of circulating (transporting) commodities. Matthew Huber notes that prior to the industrial revolution, roughly 85% of all mechanical energy came from animal and human muscle power, the rest coming from wind and water (107). The industrial revolution freed production from numerous physical (land/bodies) and temporal constraints. The intensity with which fossil fuels could be used did not change through the progression of the day, or the passing of the seasons. Steamboats, railcars and later, automobiles, circumvented the barriers to markets that long-distance travel represented, thereby increasing the sphere of commodity relations to a world scale. For the first time ever, the core energetic base of the production process was no longer human power, but rather an inanimate resource Gavin Bridge termed “geological subsidies to the present day, a transfer of geological space and time that has underpinned the compression of time and space in modernity” (48). The social relationship to capitalism also transformed; workers become more and more like a “living appendage of the machine” (Huber, 109).

Since the Industrial revolution, inexpensive fossil fuels have been normalized and internalized as necessary conditions for production and circulation. The spatial conditions necessary to sustain such a system are so prevalent (cars, trucks, highways, airports ect.) as to become nearly invisible and largely taken-for-granted. The vast claims on spaces made by this infrastructure are critical to globalization and the most successful and important logistical innovation for industry today, “Just-In-Time Production”. This mode of production fully harnesses the logic of cheap, space-annihilating transport for the following reasons: “very low coast of transport as a proportion of total costs; and the very large savings that can be made by manufacturers who use long-distance sourcing and inter-plant transfers to benefit from wage rate differentials, economies of scale, and variations in grants and subsidies to manufacturers who claim, and appear, to be creating jobs by moving them around” (Whitelegg, 67).

However, this historically specific “fossil-fuel mode of production” is poised for a dramatic upheaval in the face of peak-oil. While many speak of a looming energy-crisis in terms of a collapse or confrontation with “scarcity”, it could be reasonably argued that capitalism is experiencing the “energy crisis” in an all together different way. As James O’Conner notes, “Limits to growth … do not appear, in the first instance, as absolute shortages of labor-power, raw materials, clean water and air, and urban space, and the like, but as high-cost labor-power, resources, and infrastructure and space” (1998, 243). As the easy-to-recover oil reserves become few and far between, oil companies are exploring ways to overcome the expensive limitations to profit that deep-sea oil, Arctic oil, and tar sands reserves represent. In this sense, the peak-oil crisis is not about running out of absolute reserves of oil, but instead is a confrontation with the loss of the massive subsidy that cheap oil represents and the falling rate of profit this entails. The traditional neoclassical economic model assumes that growth is only constrained by demand (O’Conner, 1998, 243). However, when the costs of labor, nature, infrastructure and space increase, capitalism must restructure or experience crisis. To avoid crisis, the oil industry’s strategy has been twofold; (1) rely on technology development to make uncooperative oil reserves like the tar sands profitable, and (2) build infrastructure such as pipelines thousands of kilometers long to overcome the costs that vast distances represent. I think this imperative to overcome the limitations to profit is highly relevant to understanding some of the largest energy and construction projects in recent times. Both the Alaskan Oil-Pipeline and the current Tar-Sands projects in Alberta (along with the Enbridge proposal to pipeline oil across BC to China) represent the immense political and economic drive to overcome limits to growth, no matter what the spatial or thermodynamic implications.

The PBS documentary The Alaska Oil Pipeline vividly showed how the oil crisis of 1973 rationalized this controversial mega-project. After the OPEC embargo, US President Nixon signed the Trans Alaska Pipeline Authorization Act into law, disabling any further legal challenges to the project. The pipeline project mobilized near-instant work camps in the isolated Arctic terrain to work day and night on an “eight hundred mile pipeline that traversed three mountain ranges, thirty-four rivers, and eight hundred streams” (PBS). By the end of the project, 32 pipeline workers had lost their lives, and the ecosystems of Prince William Sound are still recovering from the 1989 Valdez tanker spill (PBS).

The higher the price of oil, the more incentive oil companies have to develop uncooperative reserves. However, because price is an abstracted value, or a claim-on-wealth, it cannot currently account for the thermodynamic limitations that energy-intensive resources entail. The issue of whether oil can be turned a profit is entirely mute when the amount of energy used to extract and refine oil approaches the amount of energy you recover. A true-cost accounting of the Albertan Tar-Sands project would revise the notion of profit as a clever shifting of costs onto the environment and future generations dealing with climate-change. So long as the benefactors of the traditional energy-sector hold political sway, industry will continue to rationalize its ever-expanding need for the “black gold”.

Works Cited:

- Gavin Bridge – “The Hole World: Scales and Spaces of Extraction” in New Geographies 2009, (vol 2). Harvard University Press

- James O’Conner – “Is Sustainable Capitalism Possible?” in Natural Causes (1998), Guilford Press, London

- Matthew Huber – “Energizing Historical Materialism: Fossil Fuels, Space and the Capitalist Mode of Production” Geoforum 2009 (Vol 40), Issue 1, Pg 105-115,

- John Whitelegg – Critical Mass: Transportation, Environment and Society in the Twenty-first Century (1997), Pluto Press, London.

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment