Base: version used in MDVL 302: European Literature of the 14th to the 16th centuries – “Criticism” (UBC, Faculty of Arts, Medieval Studies Programme, AY 2011-12 Winter session term 2) + a couple of upates (ex. on plagiarism, style guides)

What is the purpose of this post?

- for the practical work of reading and writing,

- including this course’s online blog-comment writing, midterm commentary, and final paper/project

- guidelines on assessment

- a selection of resources for writing

St Lucy of Syracuse: patron saint of writers, readers, and the blind, inter alia (Francesco del Cossa, San Petronio, Bologna: 1473). Hence the quill in her right hand, and a somewhat arch and sceptical expression.

As for what’s in her left hand—

—which may be read and interpreted as a representation of close reading, close up.

RAPID NAVIGATION

- ON READING:

—fast reading

—slow/close reading

—how to be a good reader - ON READING AND WRITING: COMMENTARY & CRITICISM:

= the form of written work on the course blog (“weekly commentary” space) and in the midterm commentary

—what commentary & criticism are (quick answer = a reading: on which, see “on reading” above)

—how they bring together reading and writing - ON WRITING:

—guide to commentary-writing

—some examples of commentaries

—composition

—style & usage

—optional extras: literary & rhetorical terms

—further resources for writing

—grading criteria - ON QUOTATION, CITATION, & PLAGIARISM

- A RAPID VISUAL GUIDE TO GOOD WRITING

An eternal reader immortalized, or, an extreme case of getting stuck into a book:

Eleanor of Aquitaine (tomb effigy, Fontevraud Abbey, early 13th c.).

ON READING

(1) Fast reading

- General, broad, even impressionistic, so as to form a good overall idea of the text. As distinct from slow, precise, close reading. In cinematographical terms: zooming out, for a panoramic shot.

- The first reading: flip through the pages so as to see the shape of the book as a whole: how is it organized? divisions such as sections and chapters? what sort of writing is it (prose, verse)? is there paratextual material (prologue, epilogue, any narrative frames)?

- The second reading: more slowly, say a page per minute on average. Look at this point for topics, motifs, names that jump out at you (ex. the principal protagonist’s name, other proper nouns, words or phrases that are repeated)

- Third and subsequent readings: we are now into slow territory (see further below)

- The incomprehensible, the unknown, new vocabulary, names of persons and places: think twice before stopping to consult a dictionary. Ask yourself if this element seems vital to a broad understanding of the text as a whole. If not, make a mark by it, and leave it. That is: IT IS VITAL TO SKIP AND SKIM. Working out what can be skipped and what can’t is something that comes with reading practice. Some of you may be more confident than others in this regard; some of you may have to gain confidence and learn to trust yourselves.

- This is the first part of LEARNING TO BE A GOOD READER: figuring out which of your hunches and instincts can be trusted, which can’t, and how to tell the difference between the two: the best way to learn that difference is to make notes of hunches, what action you took, and what the result was.

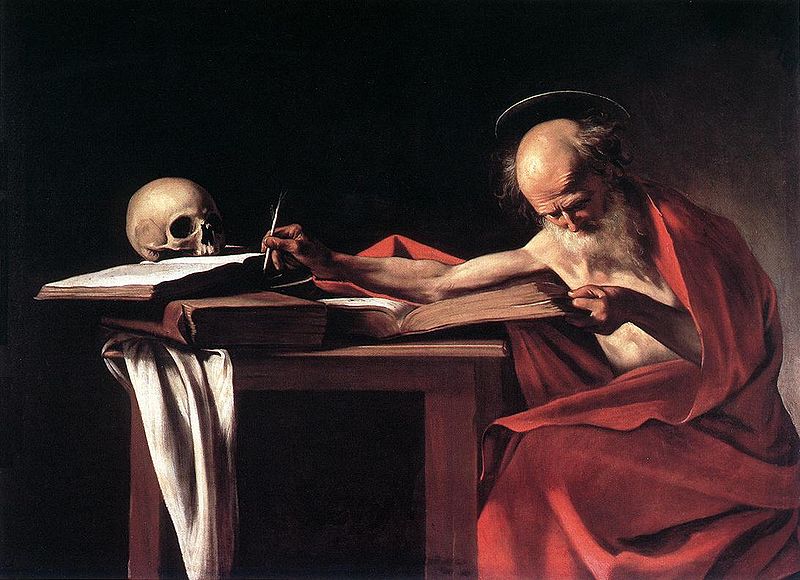

Early multi-tasking:

St Jerome (patron of translators, librarians, students) writes in one book whilst reading a second.

Caravaggio, Museo Borghese, Rome (1605/06)

- If you are not already in the habit of doing so, start writing in/on your texts. Above all, in the form of marginal comments (see example below by Montaigne). This can of course be in the form of inserted post-it notes, stickies, flags, and so on. Read when possible with a pen or pencil in your hand (or between teeth). This is an important part of “active reading.”

(2) Slow reading

- Slower, closer, more precise: the contrary motion to fast reading. In cinematographical terms: zooming in for a close-up shot, going under the magnifying-glass, under the microscope, and indeed under the skin and into the very fabric of the text…

- The incomprehensible and unknown: as before, do not look it up straight away. Make a note on your text (a “?” in the margin does nicely).

- The second reading: check those unknowns. Do they now make sense, in the light of the whole? Can they be guessed? Do they matter, or not?

- In second and subsequent stages of reading, there will be contextual and intertextual references as well as contemporary and classical allusions that it will be useful to look up. As they will play a part in making sense of the text, and in looking more closely at its construction. Wikipedia and Google are usually a good first start for quick answers (at this reading stage, NB: full-on research is a different story…).

- This is also the point to start looking out for AESTHETICS AND OTHER WEIRDNESS. Those parts of the text that do not simply convey information: all that is supplementary, goes beyond, the simple transmission of information.

• How are facts presented?

• By whom?

• From which/whose point of view?

• What sort of language is used?

• Are there deviations from the “straight and narrow” (plot development, character focalization, use of language, imagery, any unexpected or jarring element, anything else that makes you sit up with a jolt and says “hang on a minute…”)?

• Are there tangents, gaps, loops forwards and backwards?

• When you spot such deviations and detours, ask yourself what they’re doing, why they’re there at all, why they’re placed in that specific location, and what’s around it?

• Always also ask if this is a matter of stylistic eccentricity: i.e. what differentiates one individual writer’s style from that of another.

See this Guide to Writing a Critical Analysis for further questions to ask of your text.

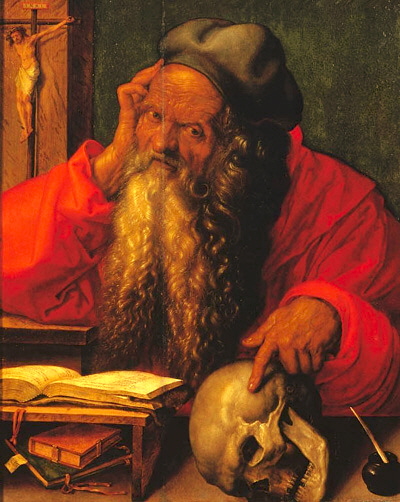

St Jerome stops to ponder,

a.k.a. “meditation.”

Albrecht Dürer, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisbon (1521)

- Just as it is vital to skip and skim in fast reading, IT IS VITAL TO STOP AND THINK in slow reading.

- This is the second part of LEARNING TO BE A GOOD READER: figuring out where to stop and pause, where to reconsider and reread, and as with the first part (above: SKIPPING), it takes practice and self-monitoring to acquire this self-knowledge …

- … for BEING A GOOD READER consists of two basic elements:

(1) good instincts/a good eye

and

(2) good reasoning/a good mind.

That’s it.

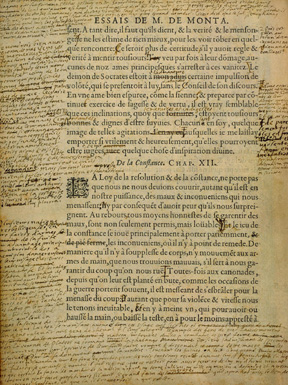

Montaigne‘s comments on his own Essays.

Exemplaire de Bordeaux (1588)

ON READING AND WRITING:

COMMENTARY & CRITICISM

As you may observe in the image above, reading and writing and reading are interconnected, and one of the main points of connection is COMMENTARY or GLOSS or EXEGESIS. The kind of writing you’re doing in this class, including the comment-/commentary-writing on the weekly blog, focusses on COMMENTARY or CRITICAL ANALYSIS or CLOSE READING. As the names suggest, this is a form of writing that is very close to the text you are reading, and indeed to reading itself.

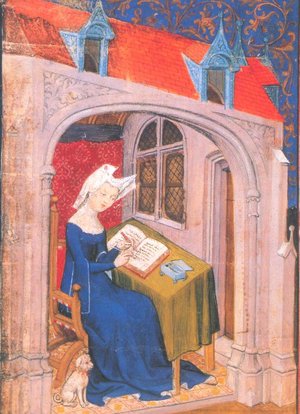

Note the following images’ ambiguous iconography of submersive literary activity—reading? writing? both?

Images above:

Marie de France,

St Augustine,

and Christine de Pizan

EXEGESIS hints at a second aspect that is distinct from reading (but in common with what a writer is doing): INTERPRETATION, the movement in an external direction of EXPLANATION and EXPRESSION, and an intention of COMMUNICATION (Lat. cum/com- : “with”). This commonality (be that to share, or to persuade through debate) is another raison d’être for the online discussions… :

While commentary should be distinguished from the general essay, the two share structural similarities: a beginning, a middle and some development, and an end. You will note that these structural features appear in all the texts we are reading on this course.

The main reason for working on the commentating kind of literary activity is to emphasize the proximity between reading and writing, as interconnected literary activities, and thus to help you to develop as (inter-connectedly) good readers and writers yourselves. Some early Medieval examples: the prologue in Marie de France’s Chievrefoil, and its intertextual relationship with an earlier one: the prologue to Chrétien de Troyes’s Erec and Enide features a moult bele conjointure that is literally a “very fine conjunction”, translated (Kibler 37) as a “beautifully ordered composition.”

What you’re doing in this course is both that “conjunction” (reading/writing, you the reader/your material) and “composition” (your writing about/based on others’ writings).

The following may be useful as supplementary explanations of what we are doing, critically speaking:

- Exegesis (Wikipedia)

- Commentary (Wikipedia)

- Explication de texte (Wikipedia)

- Close Reading (Wikipedia)

- Literary Criticism (Wikipedia)

- Practical Criticism (Wikipedia)

- The journal Glossator “publishes original commentaries, editions and translations of commentaries, and essays and articles relating to the theory and history of commentary […] The journal aims to encourage the practice of commentary as a creative form of intellectual work and to provide a forum for dialogue and reflection on the past, present, and future of this ancient genre of writing.”

They have a good short section about commentary and a fine select bibliography - Guide to Writing a Critical Analysis (O’Brien, last revised 2012)

The next item is a counter-balance that is well worth reading; a comfort to return to, to remind oneself that reading has a point:

- Doris Lessing, The Golden Notebook, excerpt from the “Preface” to the 2nd ed., 1971 (online edition 7-14). “This business of seeing what I was trying to do … ” to the end. Passionate polemic on the purpose and role of criticism and of reading: old-fashioned in some respects, unorthodox in many, and still radical as concerns the teaching and learning of literature.

The critic criticized:

Hans Holbein, marginal drawing;

Erasmus, In Praise of Folly

1st ed. (1515)

Key to the full meaning of criticism is interpretation and judgment: fair and balanced, as in court; taking into account all views and points of view, and including all sides of the argument. For above all, this is your reaction to the text, your literary appreciation: at the centre of this reading, and your writing of it (and discussion in a non-written way, ex. in class) is YOU THE READER. Critic, interpreter, judge.

What we are doing is not pure and unadulterated Practical Criticism, an attempt to produce a clean and OBJECTIVE reading. That is, a reading that is based purely on the text and utterly divorced from anything outside it: intertextual links; the contemporary real-world context; intention, production, audience, and reception; a history of reading that would include a history of critical/scholarly reading; and, last but not least, what you bring to the book. It is arguably a delusion to think that any reading by a human being can be anything other than SUBJECTIVE: that’s in the nature of the beast that is the subjective human / human subject. And so, in a compromise, you may bring to the text all your previous experience, opinions and value-judgments, other reading and research, and all extra-curricular knowledge: but only in combination with a close reading of the matter at hand, and its immediate intratextual relations (i.e., relation of each part of the book to each other part of the book, and of the parts to the whole).

The sole limits to your freedom of interpretation: POSSIBILITY (logic, sense of words, fact) and VERISIMILITUDE (no robots or psychoanalysis in the 12th-17th c., please)

The final stage of slow reading, for it to become a complete reading, is a move back out from the microscopic to the macro: this is the moment to consider INTRATEXTUAL RELATIONS (= relate a particular passage to other particular passages elsewhere in the work, and to the work as a whole). When relating your readings to the lectures, and when working on projects, consider also eventually the INTERTEXTUAL (= between works, especially those that are directly related–same writer, same topic, same form, part of same textual family ex. hero-stories, Lancelot-stories) and the CONTEXTUAL (= the world outside your book: that of the writer and his surroundings; that of intention, intended audience, and subsequent reading history; and the real, historical, material world, warts and plagues and all …).

- NBBB: brilliant commentary does not necessarily involve any “research” in the sense that you may have met in other courses, that is: the reading of or reference to secondary sources (i.e. criticism/commentary written by others, books, journal articles). It can be done entirely from first principles: that is, the combination of a primary text / primary sources (including their representations online, for example in the case of manuscripts in libraries elsewhere and objects in museums), your good reading, and pure reason.

Commentary as your reading of primary sources and as your conversation with them:

the 14th-century writers Boccaccio and Petrarch,

in an illumination from a manuscript of Boccaccio’s De casibus virorum illustrium.

British Library Royal 14 E V, f. 391 (Bruges (now Belgium), 1479-80)

The art of harmonious composition: Le Mans, cathédrale Saint-Julien; image, Daniel Clauzier. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

ON WRITING

Good reading is an integral part of good writing. Here are some other factors to consider in criticism, commentary, and other writing:

- Having an idea, having a point to make

- Uttering it clearly, arguing and developing it

- Evidence, including from primary sources such as a text

- Argument and proof

- Logic, rationality, and the reasonable

- Order, coherence, and consistency

- Sense, finding the sense of/in something, and making sense of it

- The virtuous circle of analysis and synthesis: generating further discussion, ideas, writing, reading, writing, etc. …

- Conclusions, including open questions and opening up further questions

- Style, rhetoric, and readability

- Persuasion, and the after-effects of your writing: changing the world, one reader at a time

GUIDE TO COMMENTARY-WRITING

- Reading Critically: Guide to Writing a Critical Analysis (O’Brien, last revised 2012)

EXAMPLES

A more recent case of, and on, exemplary close reading: “Spinster Aunt Wastes Time” (I Blame the Patriarchy, 2010-08-03)

Some samples: not to be used as exempla / models; may serve a dual purpose as cautionary tales… O’Brien, three versions of the same item (further later versions also exist, reconfigured and incorporated into two other items):

- first version: a talk for a Medieval Studies colloquium (2002): pages 4-8 are simple commentary

- second version: a graduate course final paper (2002-03): 9-10, 15-top of 23

- third version: the neatest of the three, inc. English translations: tidied-up version of a conference paper (2004)

GENERALITIES

ON COMPOSITION

- The Ten Commandments of Hugh Trevor-Roper (1971)

- George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language”, Horizon 13.76 (1946): 252-65. A fine commentary, incisive criticism, exemplary essay, useful guide to writing, and a handy manual on English usage. All rolled into one short, sharp, sweet piece. See also the Wikipedia article on this essay, and “Bad Writing and Bad Thinking” (Rachel Toor, The Chronicle of Higher Education, 2010-04-15).

SPECIFICS

ON STYLE & USAGE

Note that what follows is about a mix of kinds of English. We are in Canada. So Canadian, American, British (and indeed Australian, Ghanaian, Indian, Irish, New Zealand, Nigerian, Pakistani, Singaporean, South African, etc.) forms are all perfectly and equally acceptable… so long as you’re consistent (ex. choice of spelling convention).

- Dictionaries:

- Oxford English Dictionary (see also: UBC library information page)

- Merriam-Webster

- Roget’s Thesaurus (1911 ed.) at ARTFL: use “search full text” rather than “headword”

- You can access these directly on campus; for off-campus access, see UBC Library Remote Access and UBC IT VPN (NB UBC’s VPN changed in December 2009).

- Classic general-purpose style guides:

- And: Paul Brians, Common Errors in English Usage (mainly American usage)

- Major arts and humanities journal/publishing style guides; particularly useful for good citation practice:

- The Chicago Manual of Style (c/o Simon Fraser University Library)

- The MHRA Style Guide

- MLA Style Guide (c/o Purdue Online Writing Lab)

- Wikipedia

- IMPORTANT NOTE on specific citation styles and style-guides (Chicago, MHRA, MLA, Wikipedia, etc): I don’t mind which system you use provided that:

- you have clearly distinguished your own ideas from paraphrase and direct citation

- it’s clear where a references comes from (in such a way that I can look it up)

- you have used the same system of reference consistently throughout

- see further: PLAGIARISM further down

- For this course:

- If you are just starting to use style guides in your written work, this is a good opportunity to practice

- If you are already using one style guide regularly in your other courses, use it

OPTIONAL EXTRAS:

LITERARY AND RHETORICAL TERMS

Use of the following technical terms is not compulsory, and O’Brien would be the first to condemn the artistic deployment of jargon and obfuscation where Crystal-Clear Plain English would perform the same job. You may find, however, that some technical terms save you time, effort, and space; and may therefore be judged useful.

- Silva rhetoricae: The Forest of Rhetoric: the best and most comprehensive site on rhetoric on the web, at least eight years running

- Rhetoric and Composition EServer.org (Iowa State University): comprehensive metasite listing resources for rhetoric and composition

- The Prosody Guide at Arnaut’s Babel

- Dictionary of Poetic Terms at Pathetic.org

- Cornerstones to western literary criticism to the present day:

- Aristotle, Rhetoric (W. Rhys Roberts trans., 1954)

- Aristotle, Poetics (William Hamilton Fyfe trans., 1926/32; Ingram Bywater trans., 1909).

- At some point in the future, to refine analytical, critical, and argumentative skills: it would be highly advisable to read Aristotle’s Logic (the Categories, etc.), as well as the Ethics and Politics; and Plato; and to take courses in later logic: see the Philosophy department for further details; for similar reasons, courses in Politics and Law are also strongly recommended.

FURTHER RESOURCES FOR WRITING

- Notes sur l’analyse critique: Comment écrire une analyse critique? (O’Brien): French version for 300- to 400-level courses, English translation available on request

- UBC Library course pages:

– ENGL 112: Strategies for University Writing;

– ENGL 120: Literature and Criticism;

– ENGL 304: Advanced Composition - University of Wisconsin-Madison Writing Center: Writer’s Handbook:

– “Stages of the Writing Process”

– “Common Types of Writing Assignments”

– “Grammar and Punctuation”

– “Improving Your Writing Style” - Princeton University Writing Program: online resources. Particularly recommended (for writing of all sorts and at all levels):

– “Citation manuals”

– “Advice in academic writing”

– “Nuts and Bolts”

GRADING CRITERIA

- Reading Critically: Guide to Writing a Critical Analysis (O’Brien, last revised 2012)

- Commentary/critical analysis grading criteria (O’Brien).

These are general guidelines: As this is a literature/culture course, most of your grade is for content and structure (good choice of examples, relevance, an intelligent reading, well-reasoned, solid argument, acceptable conclusions with regard to all of the above). Style, syntax, grammar, and spelling will contribute to the grade, insofar as they contribute to the communication of content and structure: bear in mind that this is an exercise in EXPLANATION which will be assisted by clear EXPRESSION. - Grading Guidelines for Content-Based Courses (Department of French, Hispanic and Italian Studies, UBC)

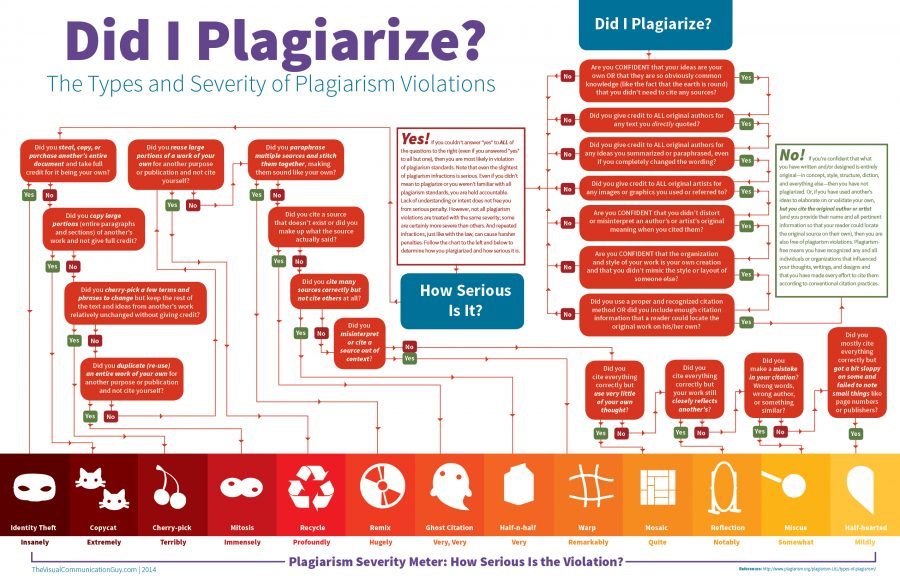

ON QUOTATION, CITATION, & PLAGIARISM

If one is submitting a piece of writing as a wholly original piece of research (this is obviously the case for projects and research papers, but also and perhaps less obviously for other kinds of written assignment), in most situations (with the exception of reaction-pieces, aesthetic appreciations, and commentary that is individual reaction) one should check who has written what on the same topic, and cite those who have come to the same conclusions as oneself. This is partly out of basic human civilised politeness, responsibility, mutual respect between authors; it is partly because copying others is cheating, as appropriating their work for yourself is stealing from them. Imitation is the finest form of flattery: but unless it’s attributed, it’s theft.

Yet flattery goes in the opposite direction, too: it is not unlikely that more than one person will reach the same conclusions as you about a text, if yours is a well-reasoned reading; consider this an indication of your good taste, and of your intuitive and rational skills having attained a respectable level.

So: While plagiarism is strictly forbidden, it should be distinguished from QUOTATION or CITATION (of a work, a work on the period, another student’s writings on the course blog), which are permitted so long as they are clearly indicated as such (see STYLE GUIDES etc. below). You should also always cite the editions to which you are referring (printed edition, online text, dictionaries and other reference works), and page numbers where appropriate.

Here is the definition I am using. It also functions as an example of citation (in the form of author/work attribution) and of quotation:

By citing, I understand referencing an author, a work, or an opinion. By quoting, I mean something much more textually precise: the verbatim repetition, in its original form, of a passage […]

–Sarah Kay, “Introduction: Quotation, Knowledge, Change.” Parrots and Nightingales: Troubadour Quotations and the Development of European Poetry. (2013: Philadelphia PA, University of Pennsylvania Press): 3

Textual, intertextual, intratextual, and contextual reference is a different thing from plagiarism.

Fear of committing plagiarism and uncertainty about what counts and what doesn’t can prevent people from referring to other works and this impoverishes not only their writing but their research, thinking, and reading. In all courses that I teach, I really really really want students to work with intertextual reference and commentary. Proper citation, quotation, and other forms of reference are therefore not just permitted but actively encouraged. They are a vital part of academic work and indeed any intellectual engagement.

Expectations about plagiarism have reasonable and practical limits. Sometimes it is impossible to know if your reading is unique. It is often impossible to consult all sources in existence… even in working on a longer project, such as a book, over several decades. This is typical and human. If in doubt, be honest: state what your working methodology was and what its limits were.

If in doubt, in any course: simply contact your instructor in that course to check, and work with them. In my own case: I’m happy to work with students before they hand in an assignment and after. If I have concerns that there might have been a misunderstanding about an assignment’s guidelines (rather than a simple case of plagiarism), we will work together on a rewritten second version.

On specific citation styles, here are the most frequently-used arts and humanities journal/publishing style guides:

- The Chicago Manual of Style (c/o Simon Fraser University Library)

- The MHRA Style Guide

- MLA Style Guide (c/o Purdue Online Writing Lab)

- Wikipedia

I don’t mind which system you use provided that:

- you have clearly distinguished your own ideas from paraphrase and direct citation

- it’s clear where a references comes from (in such a way that I can look it up)

- you have used the same system of reference consistently throughout

If you are just starting to use style guides in your written work, this is a good opportunity to practice. If you are already using one style guide regularly in your other courses, use it.

OFFICIAL ANTI-PLAGIARISM STATEMENT in THE RULES:

Plagiarism is taken very seriously at UBC. It is also often difficult or unclear what exactly it is. That can, in turn, aggravate fear of committing plagiarism (including accidentally) and of its consequences. If you are ever unsure, please ask your instructor, who will be able to help.

Plagiarism robs you of what you think and what you can learn. Avoid it. Please be reminded that your education includes academic integrity, in preparation for its application in other areas in the rest of life. Unattributed use of someone’s else work (book, journal article, newspaper clip, online material, etc) and other demonstrated incidences of plagiarism will result in penalties ranging from an F course grade to expulsion from the university when the incident is reported to the President’s Advisory Committee on Student Discipline.

This is a part of your formal relationship with the University. See further:

- UBC Plagiarism Policy

- UBC Policies and Regulations: Student Misconduct and Discipline: Academic Misconduct

Guidance on avoiding plagiarism:

- UBC Learning Commons: Academic Integrity and Avoiding Plagiarism (a very useful set of resources)

Proper citation and quotation is of course permitted, actively encouraged, and a vital part of academic work and indeed any intellectual engagement (especially in fields involving culture and literature). It is a different thing from plagiarism. It is often difficult to figure out the difference between, for example, citation and plagiarism; and learning about this is a useful part of university education. Fear of committing plagiarism can be paralysing and affect your work, limiting its (and your) creative and critical potential. Fortunately, you do not need to suffer and struggle alone: your instructor is a knowledgeable person who will be able to offer expert guidance.

If in doubt, if you’re ever not sure, please talk to your instructor before handing in your work. We are here to help.

A RAPID VISUAL GUIDE TO GOOD WRITING

DO NOT fall asleep, dream, and write it all down as best you remember it on waking (literally or figuratively).

DO NOT fall asleep, dream, and write it all down as best you remember it on waking (literally or figuratively).

Such things may result in chaos, due to the excessive influence of …

.… That Pernicious Wheel.

Aim instead for this:

with plenty of

and the further support of

so as to enable the inclusion of ornamental flourishes – which are at the same time the beautiful centre of your work, around which it is built:

Images c/o Chartres Cathedral, France; the North Rose Window being part of a gift by Blanche of Castile, daughter of Eleanor – supra – in 1230.

Images c/o Chartres Cathedral, France; the North Rose Window being part of a gift by Blanche of Castile, daughter of Eleanor – supra – in 1230.