Senakw: A Squamish village

On February 15, 1866, a group of Squamish patriarchs set out from their homes on the southwest shore of False Creek. They left their village of Senakw and headed for New Westminster—the colonial capital and an outpost on the Fraser River that was home to loggers, miners, seafarers and the first pioneers to cross the Rocky Mountains. They arrived on foot after a sloping uphill walk to their destination 20 kilometres away. They were seeking a man named Captain Ball. As the Indian Agent for the region, Ball could enshrine the village and its environs as an Indian reserve and sweep the homes of about 25 families under the shield of federal authority.

Nearly 150 years later, Ottawa still holds a portion of this property in trust for the Squamish. Abandoned and flattened nearly a century ago, the village is no more. But the reserve remains and is now one of Canada’s richest plots of undeveloped urban land.

In 2010, descendents of the petitioners who marched to secure their land unveiled ambitious plans to commercialize what’s left of the reserve. The reserve is a misshapen fraction of its former size, but the real estate is already generating millions for the Squamish Nation.

“The bearers are Indians”

According to the entourage that visited Ball that winter in 1866, 14 men, 16 women and 12 children lived at the location “with potatoe patches for each family [sic].” Ball wrote to his supervisor in Victoria, Joseph Trutch, “The bearers are Indians who have had a house of False Creek for several years.” A forester owned the rights to the trees where the families lived, Ball belaboured, “but as the Company have no interest in the land, a reserve might be marked off for them provided they did not cut the timber required by the Mill Company [sic].”

Trutch consented, and in a letter dated two years later in February 1868, granted 10 acres of land to each family. Another 18 months later, no acreage had been surveyed. Finally, five years after those first men trekked to the capital of the colony, a rectangular 40-acre reserve shot inland from the main village and gravesite.

False Creek Indian Reserve becomes Kitsilano Indian Reserve but not before a clerk identifies it as “False Reserve”

The southern bank of False Creek where the waterway opens to present-day English Bay was distinguished by a long and shallow sand bar renowned for its fishing. Men, women and families camped on the shores, which sustained fir trees and other evergreens, berries, wild rice, wildlife and birds. To the Squamish, the area was known as Senakw, OR SN’AUQ (pronounced Snoch, with breathy vowels, a soft ending like some guttural sigh, and a lisping ‘S’).

When a man named Chapxeim built more permanent lodging in the early 19th century, others followed his lead and a village of 20 to 25 families became established. They buried their dead inland near the present-day intersection of First Avenue and Burrard Street.

When the village site, graveyard and surrounding 40 acres were registered as reserve land in 1868 and then to more than 80 acres three years later, the Squamish were no longer living in a British colony but in the province of British Columbia. Senakw was now under federal authority and within the border of the False Creek Indian Reserve.

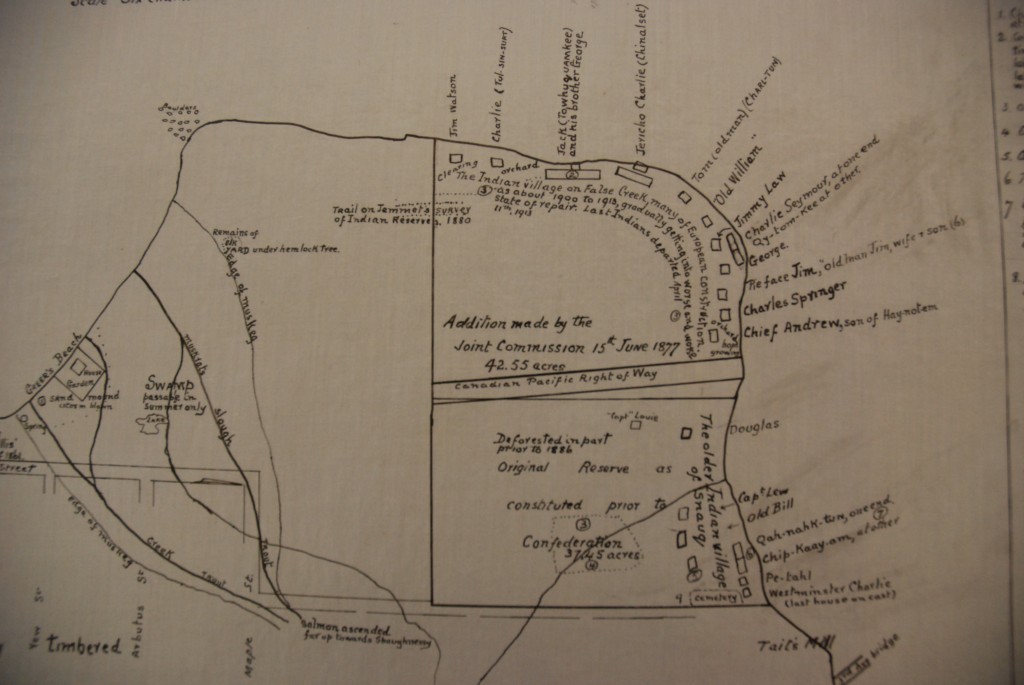

The initial site of Senakw was founded near the home of Chapxeim, seen on this map as "Chip-Kaay-am." This map was drawn in 1932 by Major Matthews, the Vancouver city archivist. Reproduction courtesy Vancouver City Archives.

A rented scow

Thirty-two years later, the land was taken away. In April 1913, the province swooped in and pressured the Squamish for land it desperately coveted. The B.C. attorney general didn’t have the right to buy federal land but he went ahead nonetheless and pushed until the head of 23 households each took $11,250 to immediately abandon Senakw.

The purchase was illegal. Correspondence with Ottawa reveals that the province was deliberately flouting federal jurisdiction. The Squamish took the money, evidence the province needed of the land’s surrender. But the Squamish didn’t own the land they lived on.

The following spring day, about one hundred people—men, women and children, grandparents and infants—were pushed out of their homes, off their land and away over the water where relatives lived on North Shore reserves. Houses were burned to the ground to make way for whatever plans the province might pursue. Graves were unearthed, and remains ferried across the water alongside the living. For the next century, the Squamish would not return to live at Senakw.

Although each family was paid thousands of dollars, this was a forceful eviction spurred by the province’s desire to expel the Squamish from desirable land—for which they had no specific plans. The Squamish were an “eyesore,” a blight in the middle of the growing metropolis that was Vancouver, a burden and a disgrace. The province dislodged the Squamish to mild protests from city officials, who cared most about securing their own claims to the land and were vying for shared ownership.

The tenor of public opinion was thus: on April 9, 1913, the day before the Squamish set sail, a morning city newspaper headlined:

Red Men Took Cash

Natives Grinned When They Became Owners of Fat Bank Accounts

No Consideration Given Yet to What Definite Use Reserve Will be Put

And the newspaper reported:

“The Kitsilano Indian Reserve, which lies at the entrance to False Creek and which for years has blocked the growth of the city of Vancouver, has passed out of the hands of the red men. It ceased to exist as a reserve on the stroke of 12 o’clock noon today, when the last of the band of Kitsilanos put his mark to a receipt and accepted a bank book, showing a balance to his account in the Canadian Bank of Commerce of $11,250.

“The eighty acres of property now belongs to the Provincial Government to administer for the progress of the city and the welfare and profit of the province at large. Bowser, attorney-general, and H. O. Alexander, who conducted the negotiations on behalf of the two parties, was present in the bank manager’s room at the Bank of Commerce this morning at the completion of the agreement.

The Squamish were not part of the discussions.

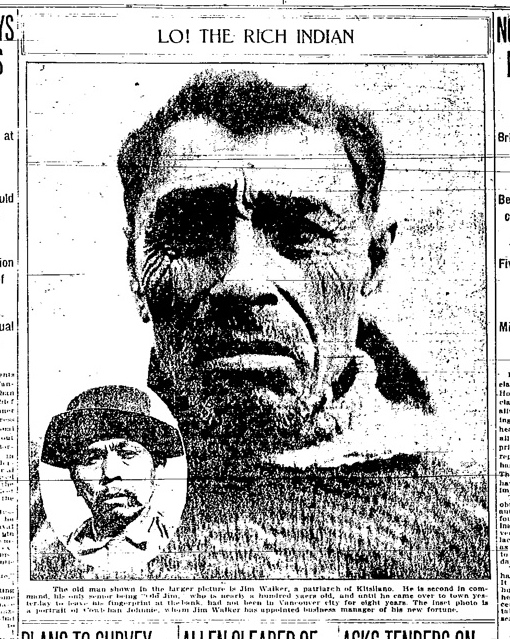

The newspaper cutline reads: "The old man shown in the larger picture is Jim Walker, a patriarch of Kitsilano."

Province left out-of-pocket

But the federal government would not forfeit the reserve.

In Ottawa, the leader of the opposition, Wilfrid Laurier, called the payment “altogether inadequate” and he was correct. The land was worth much more and had received other offers, including $2 million earlier the same year from the Chicago, Milwaukee and Puget Sound Railway Company. All bids were refused by the Dominion since the reserve was held in trust for the Squamish.

Although the province forked over more than $250,000 to secure the land, the reserve soon reverted to federal control. The Squamish did not move back and dozens of transient, unemployed labourers moved in to squat on the land instead.

Right-of-way

Vancouver’s seawall was under construction through the 1920s and ’30s, and petitions were circulating to create a continuous foreshore from Stanley Park to Spanish Banks to solidify the city’s nascent affinity for an outdoor lifestyle. Advocates argued that the seawall hinged on there being a bridge spanning False Creek.

In the fall of 1930, Vancouver city council claimed a portion of the reserve and expropriated just over six acres of land through its center to construct a bridge, linking the growing downtown core with Kitsilano. As far as Vancouver’s councilors, city planners and newspaper columnists were concerned, the right-of-way was a foregone conclusion. As justification to bisect the property, planners pointed to a bill that allowed the city to use federal and other land, such as an Indian reserve, to build infrastructure for the growing city. Similarly, sewer pipes, water pipes, bridges and highways crisscross Indian reserves in the Lower Mainland and around the province. Eighty years later, one Squamish leader described Kitsilano and other reserves as “the path of least resistance” for urban growth.

In 1931, “a valuation” of the Kitsilano reserve placed the six acres used for the bridge a few dollars shy of $133,000. But the city would not compensate the Squamish. Instead, the mayor and council disputed the sum and went to arbitration the next summer.

Fifteen months later, the city owed the Squamish $44,988 for more than eight acres. The total had been reduced by more than $7,000 because arbitrators ruled the bridge was an advantage to the Squamish.

Not only did the Squamish now have a concrete structure running overtop their centre of their land, thrusting enormous cement and rebar supports through a former village site and fishing grounds, but the six-lane Burrard Bridge was seen as an improvement to the property.

$92,500,000

The Kitsilano Indian Reserve remained uninhabited save for squatters whose boats and shacks were criminalized and sporadically raided by police. When World War Two engulfed the British Commonwealth, Vancouver became an important Pacific base and the 80 acre reserve at Kitsilano Point a strategic staging point—it was used for storing aviation supplies.

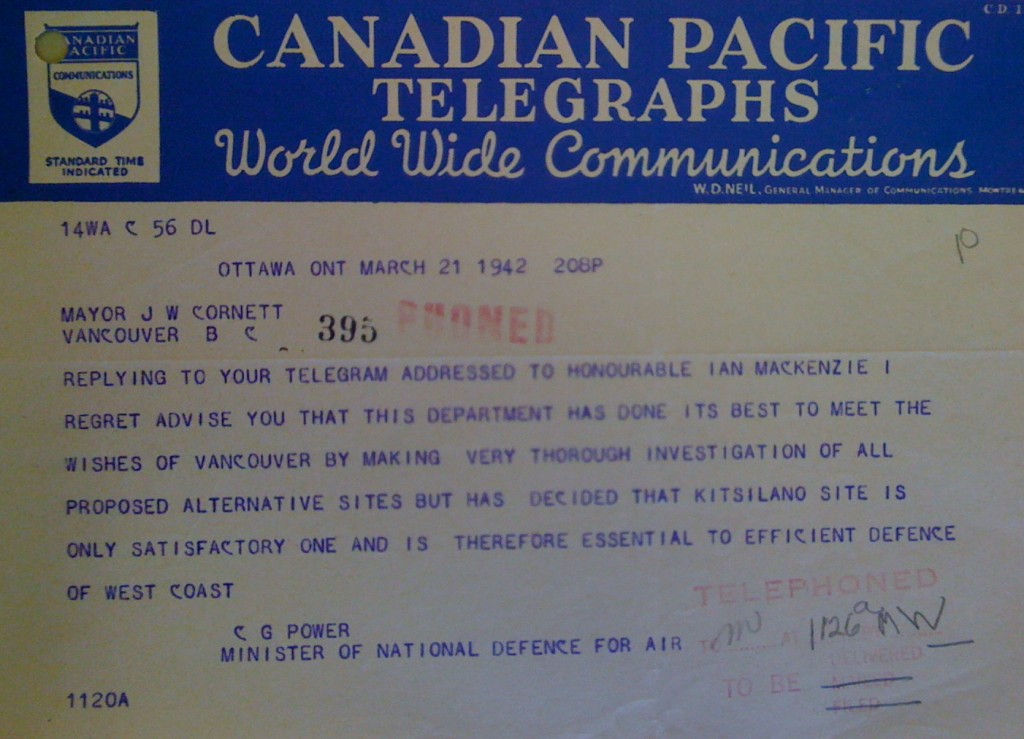

The Department of National Defence informs the Vancouver mayor in 1942 that Kitsilano Point, the location of a Squamish reserve would be used to storage base for the airforce. The city was opposed to the military using the downtown location in case it became a target for bombing and preferred a site in Marpole.

[[IMAGE: barracks]]

The land was surrendered to the Department of National Defense and after the war became a city park. In 1977, the Squamish initiated legal action and were eventually compensated $92.5 million for the loss of part of their property, which is now Vanier Park and connects Vancouver’s continuous seawall.

Yet, a peculiarly shaped portion of the 80 acres was not surrendered during the war because it was leased to the Canadian Pacific Railway. The Squamish Nation successfully sued for this land and it now forms the present-day Kitsilano Indian Reserve.