The idea to pull in advertising dollars from billboards had been percolating for at least five years when, in 2005, the Squamish asked for proposals and began negotiating with multiple advertising companies. When they finally penned a deal with Astral Outdoor Media, the Squamish valued the contract at $30 million over 30 years.

A cyclist approaches the Burrard Bridge from the south. The billboard can be seen across five lanes of traffic.

In the summer of 2006, the mayors for North Vancouver, West Vancouver and the District of North Vancouver received information from the Squamish about their intentions to plant an unknown number of billboards on reserve land near major transit arteries and intersections shared with each municipality.

The Squamish Nation did not speak publicly about any development plans until July 2006 when Toby Baker said, “It is something that meets the needs of our community, and our community’s needs are paramount.” The initial plans called for 28 billboards measuring 4-by-8.4 metres. The size was downgraded when outrage reached a fever pitch, and vocal residents of Vancouver and the North Shore bemoaned the besmirching of the region’s spectacular sea-to-sky vistas. Some also levied concerns over traffic safety and worried the digital signs would distract drivers. The total number of billboards was scaled back to 13 at six locations with a single, two-sided sign planned for Kitsilano Reserve at the Burrard Bridge.

The planning was not unanimous favoured among the Squamish Nation. One father and son duo criticized the pending billboards and on Highway 1 heading north of West Vancouver, they put up a sign with a black background and one word in white and written in capital letters—SEX—to demonstrate the crass affront of the marketing media.

William Nahanee opposed the decision of the elected band government. He thought the profit venture portrayed the Squamish as a greedy First Nation that mismanaged its surplus of cash and gave little regard to its neighbours.

He said it’s difficult to criticize or challenge councillors like Gibby Jacobs, who has held tenure and been reelected over the course three decades. Family politics come into play and individuals hold grudges for past slights, he said. “It’s like living in a glass house.”

Four times he campaigned for one of those 16 band council seats but has never been elected. He opposed the billboards but did not make this opposition a prominent part of the most recent 2009 election campaign.

The first billboard went up in November, 2009 to the west of the Burrard Bridge in sight of the former village of Senakw.

“Indians didn’t create billboards”

Reaction from the non-Squamish public was as expected. “Bucks before beauty,” headlined one newspaper. Some expressed outrage and more than 10,000 signed a boycott against companies that bought ad space. Two mayors petitioned the federal government to halt the project. Others were sympathetic to claims the First Nation needed revenue, some lamented the initial loss of indigenous land though colonization, and still others seemed to roll their eyes at the accusation that nine billboards would detract from the panoramic beauty framing the large metropolis. A handful wondered at the financial accountability of Squamish band management.

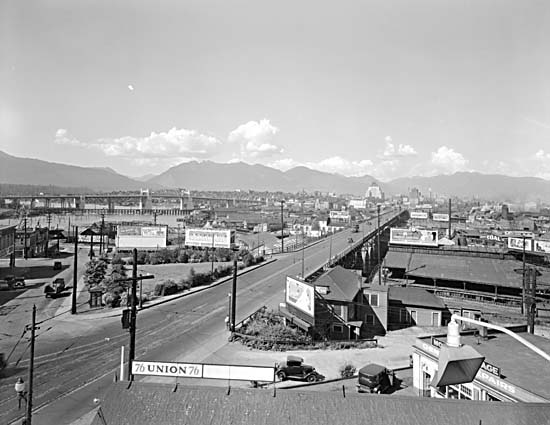

Dozens of plywood and paper billboards line the Granville Bridge. The Burrard Bridge can be seen in the distance to the west.

The loudest cry came from the scandalized. Opinions played out in the op-ed pages of Metro Vancouver newspapers, and whether they were “garish,” “dangerous,” or “unsightly,” the digital signs were liked to “Goliath lit-up billboards,” “flashy Las Vegas billboards” and “giant LEDs on a Popsicle stick.”

Like a century before, Squamish land was said to be an embarrassing “eyesore.”

Baker shot back at detractors: “Indians didn’t create billboards.”

The press as public forum

Newspaper letters-to-the-editor and radio call-in shows became the primary venues for the public to weigh in. Since they had no legal or democratic influence over what happened on Squamish land, no comment amounted to more than rhetoric.

.

Here is a sample:

“It’s really upsetting. I’m disappointed and shocked.”

— Lisa Muri District of North Vancouver councilor in July 2006 after initial plans were circulated that the Squamish First Nation would be raising 28 massive billboards around Metro Vancouver.

“Our beautiful scenery is about to be obliterated by numerous hideous commercial billboards visually polluting the Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing area and other prominent locations—and that’s just for starters if we don’t do something.”

—Nita Joy in the pages of the North Shore News, July 2006

“The reserves are Canada’s Third World, including their political structure.

“In this milieu it’s understandable that the North Shore municipalities were never brought into the Squamish plans for the billboards. Aboriginal leadership isn’t very democratic or inclusive in classic Western terms within aboriginal culture, so why would it be toward outsiders?

“A free (more or less, but not enough) press and the flow of information are essential to Western liberal democracy.

“This secrecy, the unreflecting acceptance that Indian internal politics are strictly for Indians, means that our very own Third World releases information to the wider community like Third World autocrats—when, what, and how much it pleases.

—Trevor Lautens in the pages of the North Shore news, August 2006

“There are billboards all over the city of Vancouver. It’s a great advertising tool. Why is it such a controversy now?

— Linda Johnnie, in an op-ed in The Province, August 2006

“Our eyes are naturally drawn to bright areas when we are in the dark. How many people are going to be coming off the two North Shore bridges in the pitch dark and pouring rain, trying to navigate lane changes and eits while at the same time being lured to distraction by these flashy Las Vegas-style billboads?

— Trudel Kroecher, in the pages of the North Shore News, November 2009

“I know that the Squamish band is going to dredge up the usual historical justification for their acts and get the old guilt feelings going again among the non-native community, but it is time that the Squamish band, like the Nisga’a nation, recognizes that they are part of a larger community and begin to take into consideration the feelings of the rest of us living in Vancouver.

— Debra Simmons, granted the ‘letter of the week’ in the Vancouver Courier, June 2010.