The campaign to commercialize 10.3 acres on False Creek was thrust into public in August 2003 as a fleet of paddlers pushed their canoes toward the shoreline under the Burrard Bridge.

In this ritualized gesture with ceremonial regalia, song and speech, the Squamish Nation marked the legal return of Kitsilano Indian Reserve No. 6. The First Nation invited their neighbours—Vancouver and North Shore residents—to the former village site of Senakw at present-day Vanier Park.

Elected band councillor and hereditary leader Chief Gibby Jacobs already had ambitions for development— “Anything is possible,” he said—but one message was constant: the band’s 3,600 members must ratify any proposed commercialization of the small but valuable real estate.

Chief Janice George was there and she wore a blanket she wove herself. As the direct descendant of the man credited with establishing the village of Senakw, the moment was decades in the making. For George, she was reunited with her deceased father, her grandparents, elders and ancestors through the land beneath her feet.

For George, it was personal.

For others, securing the rights and title to one of Canada’s most highly praised plots of land was political.

A fraction made of graveyards and fishing holes

Sixteen related aboriginal communities came together in 1923 to form the Squamish Indian Band. The First Nation would use that symbolic total to determine the number of elected band council seats.

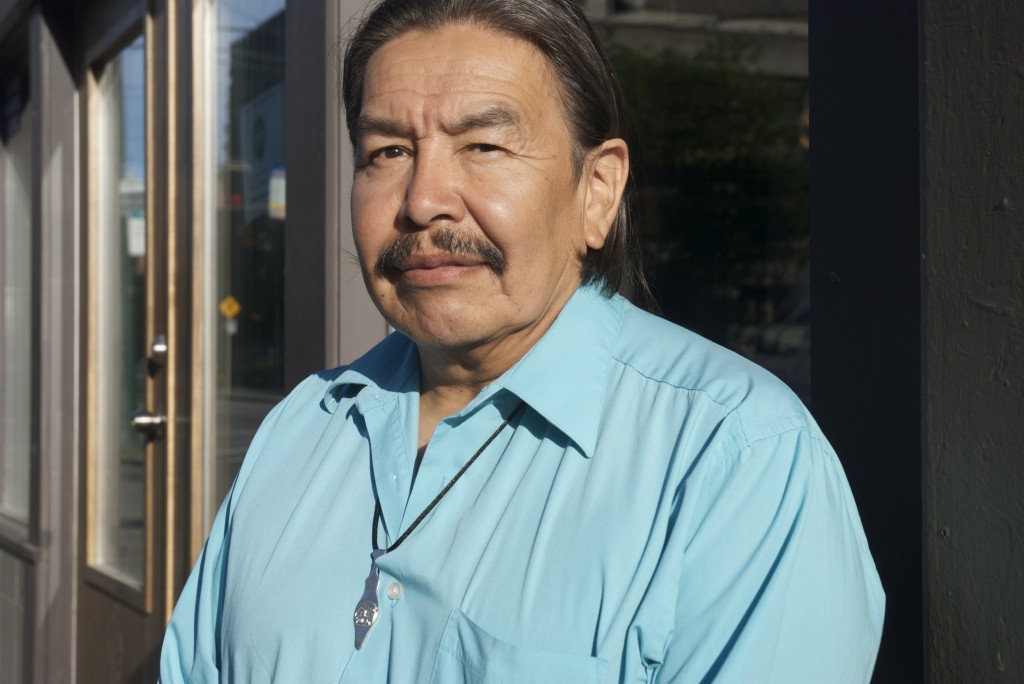

Today, the spokesmen for the Nation are Gibby Jacobs, Bill Williams and Ian Campbell, three hereditary chiefs who also sit on council.

These elected positions are charged political roles, said Williams, and successful candidates are responsible for child-care and housing, land management and health. They govern as politicians might in Victoria or Ottawa but are closer to the citizens they represent, he said, except money from the Department of Indian and Affairs is already earmarked.

“All those decisions on how money is spent, where the money is spent, are made by bureaucrats hiding behind some nice glass windows. [They] have no real knowledge of what’s happening on the ground, what’s happening to our people.”

Williams was first elected to council in 1985. He said the Squamish Nation has slowly secured greater independence.

“We kicked the Indian Agent out of our council meetings and we appointed out own chairman,” he said. Until that point in 1963, every meeting was called by the Department of Northern and Indian Affairs in Ottawa. “They managed our business,” said Williams.

With incremental political independence came economic aspiration.

Said Williams, “the second step was to try and build up the equity in the land that we have—as small as it is—to gain as much economic wealth as possible.”

The Squamish claim more than 6,700 square kilometers as their traditional lands from Whistler to Burnaby and including downtown Vancouver. (To compare, the area is slightly larger than Prince Edward Island.) Today, however their land base is limited to 23 Indian reserves, which each average 88 hectares, most of them measuring less than 16 hectares.

“If you put all of those reserves together, they comprise 0.3 per cent of our traditional landmass,” said Ian Campbell.

The band does not own any of its reserve land, which is held in trust by the federal government and left to the Squamish to manage, develop and lease.

“When Joseph Trutch and the gang decided to develop reserves in the 1870s,” began Williams, “we got 23 reserves allocated to us. While that’s beautiful in numbers, reality is seven of those reserves are in fact graveyards, six of those are in fact fishing holes.”

With no land to leverage as collateral in business transactions, Williams said the Nation is building its assets through land leases, forestry agreements and other partnerships. The Squamish Band runs an annual budget in the realm of $60 million, generating 80 cents out of every dollar through its own revenue streams, the rest coming from Ottawa for on-reserve services such as housing, education and health care.

Williams said a single house costs the Squamish about $140,00 to build and the Department of Indian Affairs contributes $20,000.

“And there’s no land value whatsoever,” he said.

A Conservative consultant

The leaders of the Squamish Nation have embraced the open market mantra espoused by an unlikely partner, Tom Flanagan.

A University of Calgary political scientist and former campaign manager for Stephen Harper’s Conservatives, Flanagan has been called a racist—and much worse—who advocates that aboriginal communities act as local governments within a larger Canadian society and forfeit indigenous claims to land and resources, rights and title.

The commercialization of the Kitsilano Indian Reserve is but one example of the Squamish embracing Flanagan’s missive that First Nations leverage the free market to build their wealth. He also advised the Squamish on land development policy, housing strategy and a real estate registry system that would allow them to tax properties on top of what the province takes.

[[I will link to greater information about Flanagan.]]

What the chief calls Injun-uity

This past year, Gibby, Williams and Campbell have each pointed at the many ways the Squamish Nation is leveraging its considerable resources to advance its economic interests. The billboards on the Kitsilano Indian Reserve are one such capitalization of the Squamish land base, bringing in millions over the course of a multi-year contract, but Campbell makes the case that the steel posts, digital displays and commercial content are about more than money—development in general and advertising in particular is political.

“There is certainly a statement that we strive for autonomy,” he said.

At 34, Campbell, is by far the youngest of these three hereditary chiefs. He represents the Nation as a cultural ambassador and has fronted the campaign to drum up awareness about ancestral and cultural rights to locations within the traditional territory. He is an entrepreneur, a capitalist, a father of two and one of the few who speak the Squamish language.

“This area is very important to us because it demonstrates tenacity and resilience of our Fist Nations people to show that we adapt, to show that although our environment has changed, that is not a new story for us. Hopefully, it also represents a new chapter to start showcasing that our history is your history that this isn’t just a segregation of us versus them,” he said in November weeks before the billboard went up alongside the Burrard Bridge. “There’s very little visible presence that shows authenticity or ancient history here [at Senakw], and I think that for us to make a mark in our land and makes a statement, shows people that we are still here and that we’re not in a museum behind glass.”

This is Campbell’s response to critics who worry the billboards will amount to little more than a blight on Vancouver’s vistas. The land is urban, he counters. It’s been altered. He challenges anyone to suggest an Indian can’t also make money. This amounts to the same tactic used to oppress the Squamish economy throughout the century, he says.

“People have a preconceived image of who I’m supposed to be as an aboriginal chief.” And he asks rhetorically, “Where are my beads and feathers?”

He sees the billboards and other development as a catalyst for change, and he trusts that a broad spectrum of Canadians will appreciate that First Nations such as the Squamish are not relegated to neither poverty nor history text books. “People [may] say, ‘Who are these people and what are their aspirations?’ Without blame, shame or judgment, I think we need to move away from some of those negative stereotypes.”

And with a sweep of his hand toward the shore of False Creek, he says, “We’re still here.”