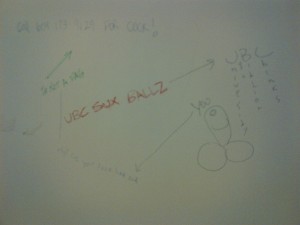

Whether it is racism, sexism, homophobia, or just about anything we deem offensive, it can be found on the wall of a bathroom stall. Bathroom graffiti has become a prominent method of sharing explicit and often unacceptable ideas or words in our culture. As these words or ideas become less acceptable in our daily conversations, they begin to appear more frequently in public bathroom stalls (Gonos et. al. 1976:42). Bathroom stalls provides the level of anonymity required to give graffiti artists full freedom to express all their thoughts that are often suppressed or considered taboo by the general public (Gonos et. al. 1976:42). Various unacceptable words are expressed in this graffiti image (found on the lower floor or Koerner Library), one may note the use of the words “fag” and “chinks” which would not openly be stated in public by anyone without anonymity due to their offensive nature. Another form of expression found in this image is an attempt to arrange sexual contact by providing a phone number and offering a service. This type of advertisement is common in bathroom stalls across America (Gonos et. al. 1976:43). One may also note an anti UBC statement in the middle of the image. All of these statements support the idea that bathroom stalls have become a forum for the expression of words and ideals that are suppressed in public (Gonos et. al. 1976:48). Regardless of their offensive nature, bathroom stalls provide an important place where those who disagree with social norms may anonymously state their controversial opinions without consequences.

Whether it is racism, sexism, homophobia, or just about anything we deem offensive, it can be found on the wall of a bathroom stall. Bathroom graffiti has become a prominent method of sharing explicit and often unacceptable ideas or words in our culture. As these words or ideas become less acceptable in our daily conversations, they begin to appear more frequently in public bathroom stalls (Gonos et. al. 1976:42). Bathroom stalls provides the level of anonymity required to give graffiti artists full freedom to express all their thoughts that are often suppressed or considered taboo by the general public (Gonos et. al. 1976:42). Various unacceptable words are expressed in this graffiti image (found on the lower floor or Koerner Library), one may note the use of the words “fag” and “chinks” which would not openly be stated in public by anyone without anonymity due to their offensive nature. Another form of expression found in this image is an attempt to arrange sexual contact by providing a phone number and offering a service. This type of advertisement is common in bathroom stalls across America (Gonos et. al. 1976:43). One may also note an anti UBC statement in the middle of the image. All of these statements support the idea that bathroom stalls have become a forum for the expression of words and ideals that are suppressed in public (Gonos et. al. 1976:48). Regardless of their offensive nature, bathroom stalls provide an important place where those who disagree with social norms may anonymously state their controversial opinions without consequences.

Gonos, George, and Mulkern, Virginia, and Poushinsky, Nicholas

1976 Anonymous Expression: A Structural View of Graffiti. The Journal of American Folklore 89:40-48.

By Terry Cole (63724082)