Gemini (known in Japan as Sōseiji) is a Japanese horror film directed by Shinya Tsukamoto. The plot revolves around a young, successful doctor, Daitokuji Yukio, who lives an enviable life with his parents and elegant wife, Rin. The table turns when his long lost identical twin brother, Sutekichi, returns from the slums and takes over Yukio’s life through a twin switch. Purposely set in the Meiji Era of Japan (1868-1912), the film explores the themes of social segregation and the extremes of human civilization. It also gives insight to life in Japan during this historical period.

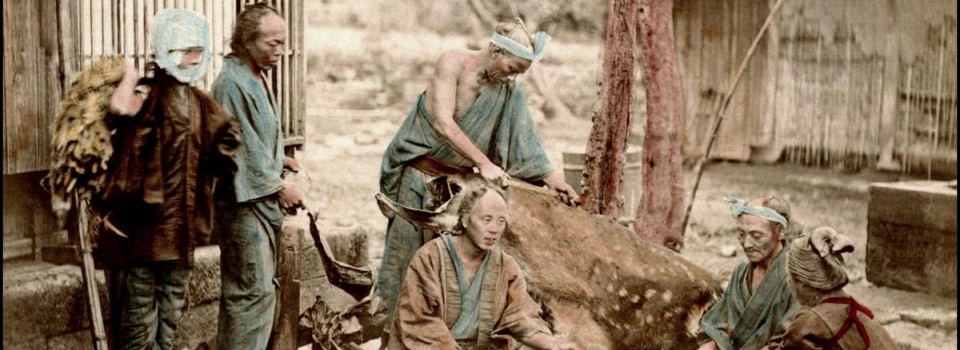

Throughout the story, there is a clear segregation between the middle-upper class and the degraded residents of the nearby slum. This can be seen when Yukio choses to attend to the injured, affluent mayor rather than a mother with an infant from the slum. He later tries to justify his actions, claiming that the slum dwellers were evil in nature, and should be wiped out with fire. Minorities during the Meiji era were classified as the hinmin (poor people, slums), hinin (non-people, which included prostitutes and criminals), or the burakumins (butchers, death workers). Just like how Yukio points his concentration toward wealthy patients, the upper class at this time period disapproved of those beneath them and viewed them as filthy, naturally sinful, and as social outcasts.

In the two polar ends of the social spectrum, the middle-upper class and the hinmin civilians are portrayed through an obvious distinction. Yukio and his parents, who belong in the upper social ladder, are seen wearing clean suits, ties, or kimonos with formal postures in their everyday routines. They are also seen with maids, or helpers around their well-organized, spacious house. On the opposite end of the social caste, are those who dwell in the slums. These seemingly-monstrous people are characterized with mismatched clothes and dirty, messy hair. Sutekichi and Rin (before meeting Yukio) are seen living in a wrecked house depending on their habit of thieving for simple survival. Other immoral acts such as murder are also present in this setting.

The table of this Japanese social structure was turned around when Yukio’s identical twin, Sutekichi, who was left for dead since birth, shows up, traps him in a dried-up well, and takes over his life. The animalistic nature of human beings are also seen in the tormented and frustrated Yukio, when he begins to take his evil brother’s filthy appearance, eating rice with Sutekichi’s spit dumped on the ground; much like a wild, hungry animal. Covered in mud with red eyes, Yukio is being put into the shoes of the slum dwellers, much like his brother if he had ended up being his parent’s reject. Yukio’s animalistic nature is also seen when he strangles his evil brother to death.

Whether it is the discrimination toward the poor people from the rich, or the hinmin people’s immoral behaviours, the idea of the separation between social classes during the Meiji Era and the lecherous nature of human beings are both properly innovated in Gemini. The film brings a social issue at the time to light, and is told through an interesting, psychological tale.

*Edit 11/15/2015: minor adjustments for clarity;

Added: sources on the discrimination of Japanese minorities, burakumin

- http://www.japanesestudies.org.uk/discussionpapers/2005/Ito2.html

- http://www.nytimes.com/1995/11/30/world/japan-s-invisible-minority-better-off-than-in-past-but-stilloutcasts.html

Changed original image into one of the burakumin to better relate with underlying topic.

*Edit 11/20/2015: took out redundant information; additional grammatical adjustments