Harlem Society

Mar 19th, 2013 by becprice

Through migration, urbanization and subsequent occupational differentiation, the years between 1890 and 1920 saw the development of new African-American enclaves and new social and economic leadership groups throughout the nation (Fultz, 98). Newly sprouted mass urban markets created new job opportunities, giving rise to a black middle and professional class. According to Fultz, this new middle class and professional group was distinct from the older African-American upper class (those who had established themselves in Northern cities prior to the Great Migration) in terms of their racial philosophies and orientation towards the black community. The new middle class was particularly race-conscious and was concerned with securing their position as leaders of the black community (Fultz, 106).

In 1910-1920, W.E.B. Du Bois ardently campaigned for the need for higher education for blacks. Education was closely related to race, class and status, so it became a source of material pride for the new middle class and professional blacks. It thus became a sort of criteria for the legitimacy of African-American accomplishments both within the black community and to white society; education functioned as an “important basis for status and stratification within the African-American community,” as well as a tangible reiteration of how blacks could “measure up” to the greater white community (Fultz, 105). Education essentially reflected and justified the new middle class’s position as black elite (Fultz, 105).

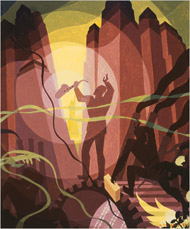

Aaron Douglas’s painting titled “Song of Towers” was one of many pieces in a collection that he called Aspects of Negro Life. Douglas is known for documenting what critics called “the Negro personality.”

Larsen takes note of the discussion of education, incorporating it as a figment of debate for Irene and Brian. When Irene brings up the fact that she would like to discuss Junior’s schooling with “serious consideration,” Brian clearly belittles the black bourgeoisie preoccupation with education when he remarks that Irene is making a “molly-coddle” of Junior by obsessing over “a little necessary education” (Larsen, 188-189) The conversation ends with Irene expressing to the reader that “a piercing agony of misery” had settled in her heart, and that she felt “willfully misunderstood” (Larsen, 189).

The “Negro Welfare League” that Irene chairs is inferred to be a reference to the National Urban League or also known as the National League on Urban Conditions among Negroes. The nonpartisan organization engaged in “community-based work to secure for African Americans equal access to employment, education, health services, housing, and social services” (Fultz, 107).