A Romantic Spell: The Great Migration and the Birth of the Harlem Renaissance

Mar 19th, 2013 by becprice

“I was in love with Harlem long before I got there.”–Langston Hughes, critically renowned Harlem writer

“I was in love with Harlem long before I got there.”–Langston Hughes, critically renowned Harlem writer

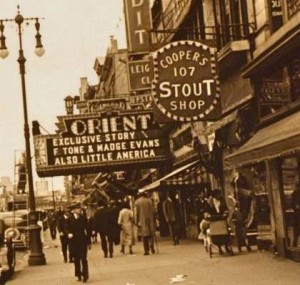

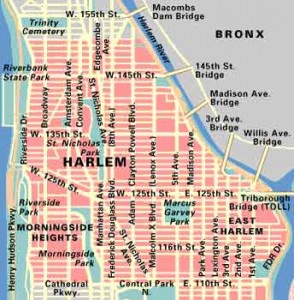

At the turn of the century America saw an mass relocation of previously southern- based African Americans to northern cities from 1910 until the 1920s. Affordable housing and new job opportunities in the city after World War I were two factors contributing to the influx of African-Americans. This movement was referred to as the Great Migration Fortune-seeking blacks from the South seized the demanding wartime economy to migrate north, where socio-economic opportunity and a less vicious racial climate were expected. Popular destinations included New York City, Chicago, Kansas City, St. Louis and Detroit. However, no city in the north captured the imagination of blacks quite like Harlem did, and an overwhelming majority of blacks flocked to New York City, settling into a section of Upper Manhattan called Harlem. Harlem soon became the “black capital of the Big Apple.” Harlem housed a diverse population of blacks from different socio-economic classes and geographical origins. By 1928, Harlem alone claimed 200,000 black residents (Stewart , 18).

“Harlem….draws immigrants from every country in the world that has a colored population either large or small. Ambitious and talented colored youth on every continent look forward to reaching Harlem. It is the Mecca for all those who seek Opportunity with a capital O.” —The Saturday Evening Times, August 1925

New York was a city that spoke to “black hopes and dreams” (Stewart, 18). New York City’s reputation as a cosmopolitan hub and launching pad for up-and-coming artists inspired a particular demographic of artistic African-Americans to venture to the Big Apple. With its publishing houses, theatres, galleries and pubs in such a close radius, New York City provided black artists with a unique landscape of venues to hone their crafts that were otherwise not available in other parts of the United States (Dorsey).

With Harlem as a home-base and the rest of the city as a critical backdrop, what became known as the Harlem Renaissance (known as the Negro Renaissance at the time) began to flourish.

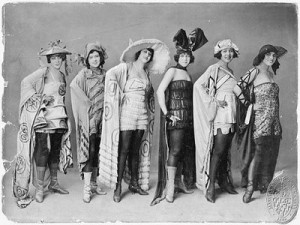

In its broadest terms, the Harlem Renaissance was a social and cultural project of African-American self-identity. The Harlem Renaissance was physically manifested in various artistic and creative outlets, including visual art, literature, dance, theatre and song. The Harlem Renaissance was the first cohesive cultural movement in African-American history (Bernard, 30).