I will begin this post by defining Indigenous futurism and further illustrating how this concept applies to Skawennati’s Timetraveller™. Following this, I have included a machinima treatment for a new episode of Timetraveller™.

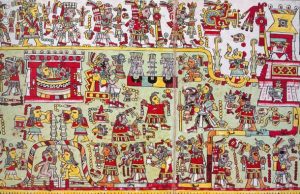

Indigenous futurism, as a concept, is a way of approaching the idea of ‘Indigeneity’ by understanding it through a digital and contemporary framework. Simply, as contemporary Indigenous artist Skawennati articulated, Indigenous futurism is a way of imagining Indigenous people in the future, through digital means, in order that such a future may be able to take place. The origins of the word “futurism” comes from the Italian futurismo, referencing a movement occurring in the early 20th century. Though, this is where the word originated, the Italian futurism movement and Indigenous futurism share very few similarities in ideology or history. Italian futurism focused almost exclusively on the replacement of anything considered ‘traditional’ with new ‘modern’ technology and beliefs. To this end, Italian futurism incorporated significant violence into their ideology. Indigenous futurism instead primarily focuses on digital and interactive media techniques that can be used to convey tradition and storytelling.

Several moments in Skawennati’s Timetraveller™illustrate this concept, however I have selected one episode that truly characterizes some of the main themes. In the episode titled “A.D. 2112”, Karahkwenhawi travels to the Powwow of the Future and witnesses not only Indigenous peoples in the far future but a far future that is defined by Indigenous peoples and their cultures. This episode embodies the understanding of futurism as picturing Indigenous peoples in the future – it does so and goes beyond. Not only do indigenous peoples exist in 2112, according to Skawennati, due to Indigenous activism, Indigenous people are strong and deeply connected to their histories and cultures. A connection to culture is specifically demonstrated by the powwow aspect and traditional dancing styles. However, the Indigenous fashions that were promoted at the event were considered modern and chic, illustrating the widespread acceptance of Indigenous culture. The emcee of the event told the story of how Indigenous peoples were treated by American and Canadian governments, focusing on the acts of resistance by Indigenous peoples, ending with their sovereignty and freedom. Overall, Indigenous futurism combines aspects of technologies, new media and storytelling to assert sovereignty. Sovereignty, in this context can mean screen sovereignty, ownership of their culture and traditional stories as well as land sovereignty and stewardship.

Episode: ‘A.D. 2016’

Basic Premise: Karahkwenhawi and Hunter are now full-time time-travellers using their Timetraveller™ glasses from Hunter’s time in year A.D. 2121. They have been happily cohabiting and travelling through important periods in Indigenous history. Hunter suggests that they visit an occurrence closer to Karahkwenhawi’s time – similar to Oka, where they first met. Hunter wants to show Karahkwenhawi that not all Indigenous rebellion in her lifetime is bitter and hopeless. They time travel to Standing Rock, North Dakota, arriving on December 28th 2016. The US military is set on building a pipeline (Dakota Access Pipeline) on the traditional unceded territory of the Lakota Sioux. The land is currently being held in peaceful protest by Indigenous people who are known as the “Water Protectors”. They aim to protect the Missouri river from potential oil pollution. They also are on the territory to assert sovereignty and protect traditional Sioux burial grounds. This event has since gained fame, and remains renowned in the future as an example of successful Indigenous resistance.

Sets: Here I have included several examples of the digital sets I have envisioned for the Oceti Sakowin camp. I found each reference on Second Life, a platform where an individual can interact with chat spaces using a digital avatar. These spaces are beautiful, incorporating the natural landscape alongside the versatile interactive space. I also chose a number of these for their interaction between the “new” and the traditional as depicted in this digital space.

Aside from these pre-made spaces on Second Life, there are existing images of the actual Oceti Sakowin camp that could be used to create specific spaces. Emphasis in set-building must remain on the proximity of the militarized police forces to the perimeter of the camp, and the spaces of prayer within the camp.

Characters and Costumes: Hunter and Karahkwenhawi are both charcaters from previous episodes of Timetraveller™. If you are unfamiliar with this series of machinimas (digitally-created films), you can find previous episodes here. For certain scenes in this episode, both Hunter, Karahkwenhawi and Kaya all wear traditional regalia associated with the Mohawk nation and indicative of status. For most scenes, however, they wear warm contemporary clothes fitting for the icy weather in North Dakota. As additional clothing pieces, they also sometimes wear bandannas to cover their mouths for protection against pepper spray.

Summary of Events:

Upon arrival, they meet Karahkwenhawi’s mother, Kaya (unnamed in the original series so I have chosen a name), who is an elder at the Standing Rock Oceti Sakowin camp. The Oceti Sakowin camp is the largest camp at Standing Rock. She emerges from a sweat tent and immediately recognizes Hunter and Karahkwenhawi. The camp has spaces like sweat tents and drumming circles for prayer and spiritual practices. It would be a relatively peaceful experience if not for the constant threat of violence and the military tanks parked a short distance away. Indigenous and non-Indigenous people from every part of the world are recognized here and are praying in solidarity with the Lakota Sioux.

While this gathering happening, Hunter explains that, all over the world, protests are being held by environment activists and Indigenous groups. Their aim is to show solidarity and to get National banks to pull their funding for the Dakota Access Pipeline. They also wish to highlight some injustices experienced by the Water Protectors at the hands of local police, including the use of water-cannons and rubber bullets. The infamous Republican United States President-Elect Donald Trump, following a months-long campaign based on fear and racial discrimination, is poised to assume power following the more liberal Democratic Obama government. Rumours circulate that he has invested in the DAPL, and would be unwilling to consider a sovereignty claim. All the media sources across the world are focused on North Dakota in this moment.

Days pass at the camp. The atmosphere of the camp is predominantly beautiful interspersed with moments of violence. US military veterans arrive in the hundreds to volunteer their time. Hunter, Karahkwenhawi and Kaya spend their days with behind the scenes helping prepare meals for the camp, engaging in prayer and listening to elders’ stories. Karahkwenhawi and Kaya reconnect after being separated for so long. They are also hearing rumours that people (mainly young non-Indigenous environmentalists) are becoming increasingly violent at other camps.

December 31st, New Year’s Eve 2016: RVs parked at the site receive very little satellite reception but just enough to watch the ball drop in Times Square on a tiny TV screen. The whole Oceti Sakowin camp counts down together. Hunter of course knows what will happen, however he does not tell Kaya or Karahkwenhawi. At 12am, the banks’ contracts with the pipeline expire, and due to the conflict over the last few months, none wish to resubmit to a new contract as it may never be fulfilled. The police forces remain, but social media interactions become frenzied within the camp. The campers with RVs are now focused on tuning in to media channels.

Hunter, Karahkwenhawi, Kaya, and the Oceti Sakowin camp begin dancing and drumming at the front line and don’t stop until the early morning. By late afternoon on the 1st of January, the Sioux Water Protectors order that the militarized police units turn back, leaving the camp free. The video cuts to the last tank slowly leaving the encampment. The episode ends with Karakhwenhawi and Hunter saying their farewells to Kaya and others they had met at the camp. Hunter and Karahkwenhawi put their TimetravellerTM glasses back on an appear again in their 2121AD apartment.