In general, I think Inquiry projects are a great way to provide students with choice in how they want to demonstrate their knowledge. During the initial stages of our inquiry project, the class brainstormed numerous ways they could demonstrate their learning using a padlet wall (Demonstrate Our Learning!). To capture the truly unique journey of the inquiry project, I asked each student to create an ongoing folder for the project, which included their detailed learner profile (indicating what they needed in order to learn best during the project’s execution), their main inquiry question, subquestions for researching purposes, and their preferred method of demonstrating the knowledge and understanding they acquired through the project.

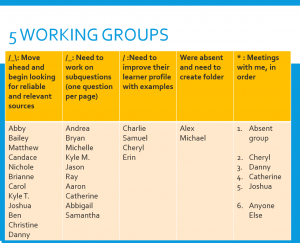

The students were given the criteria for the folders on an ongoing basis, and I provided written feedback for each of the required components. When I reviewed the folders as a whole, it was evident that each student was at a different stage in their learning process. I decided to try the “triangle” approach, which was a strategy we acquired during our assessment course. I drew all three sides of the triangle on the folder if the students had completed all required components to the agreed upon standards and were ready to progress to the next stage. Students were given two sides of the triangle if they needed revision in one aspect of the folder, and only one side of the triangle if they needed revision in more than one area of the folder. With any level of triangle completion, students could be given an asterix (*), which meant that they needed to conference with me to clarify or elaborate an aspect of their project. With all of this information, I created a table so that students could see where they were at, what they would be doing during class time, what they would do once they finished, and when they needed to meet with me. I wrote the conferencing lists in decreasing order of urgency, and allowed students who were not on the list to sign up under the title “Anyone else.” I believe this process and the project as a whole allowed for successful differentiation of student learning.

“I found this method extremely effective in terms of students working at different rates, and scheduling individual conferences. However, as I showed it to the class, I also realized that it may make some students feel uncomfortable given the chart displayed their progress to the class. So I addressed the issue by emphasizing that everyone works and learns at their own rate, that this is normal, and encouraged. The process empowered the students to work hard to get the additional parts of the triangle, and I had several students finish their part, show me what they had done, and asked for their triangle to be completed.

I held the conferences at my desk in an order based on who needed it most (ie. who could not continue without direction to who just needed a few suggestions or minor revisions). I thought this worked really well. Many students were actively on task, and many students came up to discuss their progress and their projects during the “Anyone else” conference time. They have made some great improvements on their topics, and I got a chance to talk to them one on one about the direction of their work.” Week 3 of long practicum

Another way I believe I successfully differentiated assessment and appreciated the varied journeys of student learning, was during a science assessment. After explaining that everyone’s journey was different, I told the students that I would have three separate tests available. The tests required the same knowledge, but at varying levels of depth and application. I created a test rubric based on the BC Curriculum that would be used for all three tests, showed the rubric to the students prior to the tests, and explained that the rubric would hold more weight than the numerical score (I chose to include the numerical score because it was what students requested). I gave the students a practice test which covered the same concepts to try on their own, and then we went over the answers as a class. I explained that the practice test was at the same level as the more in depth of the three available science tests, and that they could use this practice test to informally assess where they were at with relation to the expectations. In hindsight, I should have also had the students use the rubric themselves to assess their learning based on the practice test, so they could better understand how I would be assessing their level of comprehension with a rubric in lieu (or in this case, in addition to) numerical scores.

After the practice test, I asked each student individually which test they wanted to take. This acted as a form of self-assessment, and let me know where each student thought they were in the class. Once I marked the tests with the rubric, the students were given an opportunity to review my feedback and then review their course notes. Students were encouraged to book an appointment with me to explain what they now knew, and how they have improved their understanding, so I could adjust their rubric accordingly.

As evaluation was necessary for the latter portion of my extended practicum due to end of term reporting, I had used the opportunity to experiment with alternate ways of summative assessment. This process was significantly more work than a typical end of unit test, though I believe it helped the students feel more successful, and encouraged them to challenge themselves. The concept of a rubric on a test (especially as the same rubric was used for all three variations of the test) was initially confusing for the students, which is why I would opt to do more front-loading with the use of exemplars the next time I use this process. I have come to realize that rubrics can take a lot of practice to get right, and can be difficult to create so that all possible submissions can be reliably assessed. However, co-construction and student revision significantly helped the process, and along with front-loading this will be key for my future practice.

Due to time constraints, I made it optional to meet with me about the feedback to improve their evaluation, however if I were to redo this process, I would have all students demonstrate their use of feedback through either a written reflection, a project, or a conference. As stated in my philosophy, I believe that providing students with the time to read, reflect and act on feedback is one of the most important aspects of assessment. I tried to incorporate this component into several other assessments as well. After students provided comments on peer-assessments, or after I provided comments, I allotted class time to thoroughly read the comments, make notes on how they will use the comments to improve their work, and then to act on the comments. This worked particularly well during a persuasive essay unit (First Draft – Peer Assessment, Second Draft – Teacher Assessment ), and it is a practice I plan to continue.

Follow

Follow