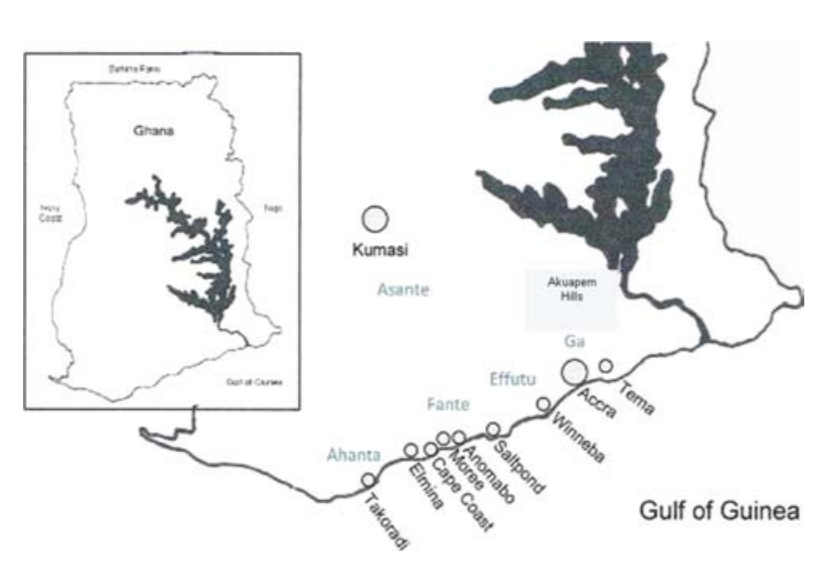

The remnants left behind in Anomabo, a town on the coast of Ghana (figure 1), tell a story in the late 19th century of the elite members of the Gold Coast colony, known today as Ghana. They were constructing their own elegant mansions utilizing an popular British architecture styles1 that not only embraced the modernity and prosperity of the period but also rejected the British administration whose rules constrained them. Especially between the 1870s and 1920s, façades of homes built for and by Africans were very much inspired by British styles. The Justice Akwa residence is an example that displays the hybrid style combining British stylistic elements, an Afro-Portuguese sobrado plan1, and local ideas of space and organization. The colonial styles and plans were appropriated and transformed to communicate the household’s desire to achieve equal status with the British hegemony and connection to modernity.

Anomabo was a central town and an active international port of commerce in the 18th century during the peak era of the Atlantic slave trade. It was inhabited mostly by the Fante ethnic group. The Fante state worked as a middlemen to bring enslaved captives from interior polities, such as from the Asante empire, to merchant ships on the coast2. The slave trade history of Anomabo started to reveal the African exploitation of the transatlantic slave trade. As one of the busiest slave markets and commercial trading ports on the Gold Coast, many influential African political authorities, a new class of wealthy merchants, as well as the long established African elite class prospered from the mid 18th century into the 19th century3 in Anomabo.

However, since the British formed the Gold Coast Colony in 1874 and controlled the Atlantic slave trade as well, the British hegemony strategically assigned political authority to the easily manipulated traditional rulers and weakened the power of the long established African elite class by separating them from the ruling hierarchy under the new British colonial rule. The British colonizers at the time also didn’t want their culture to be “contaminated”2 by African traditions. However, it was exactly this that triggered the Gold Coast wealthy elites to declare and emphasize their rights through mimicking their visual culture as a form of resistance. This can be seen in the posuban shrine (figure 2), with a British crown on the omanhen’s stool, a local symbol of rule which referenced aspects of British culture1.

The Hybrid British power symbols were not only seen in art forms such as shrine sculptures, it was also evident in the local building designs. Architecture was one of the prominent medium through which Fante elites expressed their resistance to British colonization and the desire to present themselves as worthy of increasing political control and status.

Zooming into one of Anomabo’s residential houses, the Justice Akwa residence (figure 3) was constructed around 1900 for a Fante agent for Cadbury Bros., the English chocolatiers1. This family house demonstrates the trend of stone nog houses in Anomabo at the time, identified as the Coastal Elite Style, which combines elements of the Afro-Portuguese sobrado, British stylistic elements and the European Palladian architecture1.

Stone nog construction (figure 4) originated from Europe and refers to the packing of small stones, shells, corncobs, and other materials with a lime-based mortar into a wood framework to construct walls in layers. This Nog house have brick facing and very thick walls, around 16 inches4.

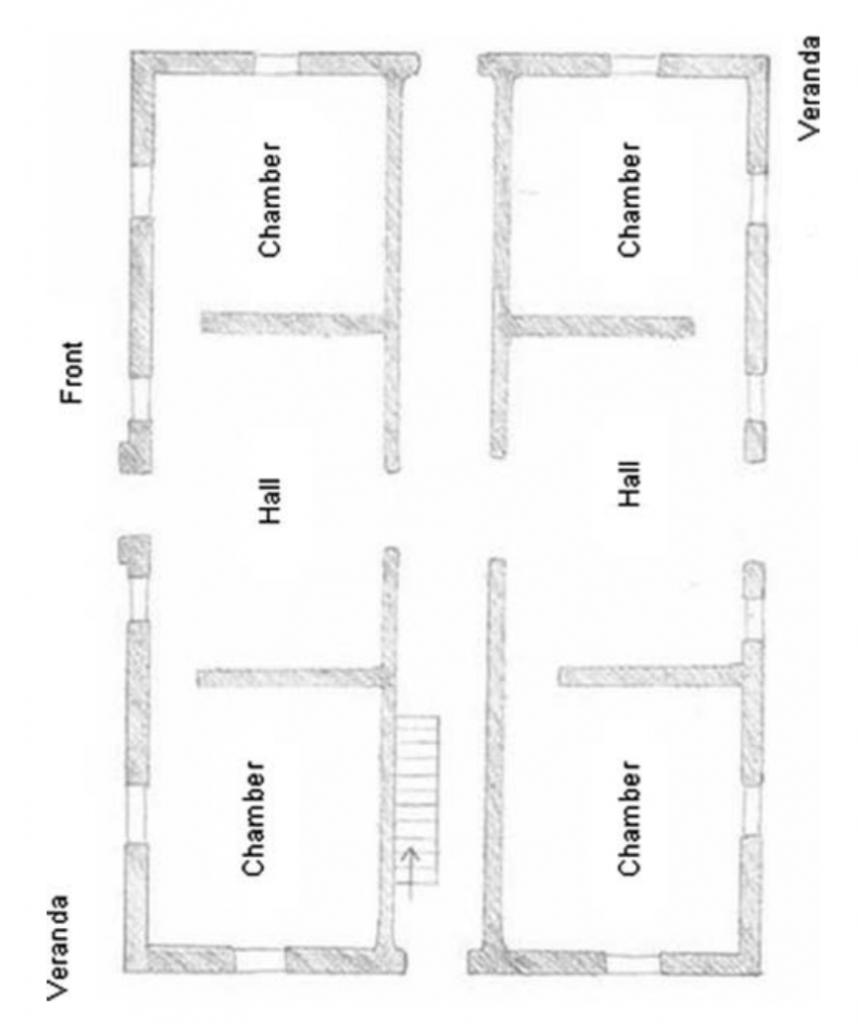

The sobrado plan (figure 5) has a second-story timber veranda and an interior corridor with two interior doors, one to each side hall4. Each side consists of chambers and a hall accessible from the central corridor. Both floors are identical and the arrangement is mostly symmetrical. The coastal Ghanians desired the sobrado plan because it was seen as the cosmopolitan culture of European colonists, as the repatriated African slaves trained by European missionaries that were building the initial structures in Brazil showed modernity through how they were dressing and speaking1.

Although it has now been removed, the Justice Akwa residence once incorporated the two most popular architectural styles in Britain during the 19th century, the classical British Italianate and Queen Anne stylistic elements, through the addition of entrance pilasters, entablatures over doors and decorative sills on windows. Local bricks were used and three rows of brick formed a stepped entablature4. Akwa likely learned of these styles through the spread of the “pattern books”1 which were distributed throughout the British Empire. The book was popular among rising middle classes and Akwa probably wanted to implement the designs depicted within to represent his rising status in the community. The Queen Anne elements used in the Justice Akwa residence can be compared to Frederick Anthony White’s London home (figure 6) built by Richard Norman Shaw1. Both buildings have similar brick patterns and an elaborate entrance, but due to the warm climate and material restrictions in Ghana, Anomabo homes reinterpreted the European styles and have lower roofs and the addition of verandas1 to allow cool breezes to circulate upstairs. These verandas typically incorporate interior arches as a featured design element, which is a style reminiscent from the Methodist Mission. Displaying the arches was also a way to display wealth of the family4 as arch forms are more expensive to construct than straight piers.

Notably, the exterior of the building also shows classical British Palladian symmetry. However, the interior walls, specifically the wall separating the chamber from the hall in the top right of the plan, emerge from the left, while the other inner walls emerge from the right. This staggering of an asymmetrical element within a symmetry is referred to as off-beat phrasing4. This is a common type of aesthetic seen in West African music and textiles (figure 7) and it continued being applied to African built residential architecture. Off-beat phrasing allows for diverse combinations of architectural designs resulting in highly creative displays of status. Although the coastal elites borrowed elements from the Europeans and Afro-Brazilians, they transformed them into something recognizably African. This two-story compact massing, with British and Afro-Portuguese architectural styles, was later spread and incorporated into other home designs of interior established Ghanian patrons that were also desired to be identified as civilized society members3. Interestingly, the coastal elites initially built this hybrid vernacular architecture to also differentiate themselves from nnonkofo1, which are the enslaved and inland peoples that were thought as uncivilized. They wanted to impress the resident British and be recognized as superior cosmopolitan individuals.

Many of the stone nog structures that survive today date between 1900 and 1920, and are located primarily in Anomabo and Cape Coast4. While the sobrado was considered to be well-suited to the urban environments of the African coast, the corridor, judging from today’s uses2, appears to be a space that does not function well for coastal Ghanaians. This shows that the design intentions employed sometimes lacked consideration of practical use.

Overall, through the reinterpretation of the European styled architecture, the traditional Fante architecture of rammed earth houses were transformed into colonial period Italianate and Queen Anne style stone nog1 residences through cultural appropriation. Through looking at the Justice Akwa residence, it reveals the struggle of political power in coastal affairs between the local elites and the British hegemony in Ghana. It is evident that there was a widespread desire of Africans to showcase their wealth and status as civilized and educated individuals that are capable of self-governance. The British imitation styles used by the coastal elites in Anomabo act as a cloak that was a symbol of mimicry of British power, as well as an act of empowerment of the coastal African elites by using British power symbols1 and the appropriation of European Palladian style to attempt to regain power from the Europeans.

_____________________________\\___________________________

Notes

- Micots, Courtnay. “Status and Mimicry.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 1 (2015): 41-62. doi:10.1525/jsah.2015.74.1.41.

- Anyim, Daniel. “We Sold Slaves Too: The Disappearance of Anomabo and Fort William In Public Narratives Surrounding The Atlantic Slave Trade,” PhD diss., (Central European University, Budapest, 2020).

- Law, Robin. “The Government Of Fante In The Seventeenth Century.” The Journal of African History 54, no. 1 (2013): 31-51. doi:10.1017/s0021853713000054.

- Micots, Courtnay. “African Coastal Elite Architecture: Cultural Authentication During The Colonial Period In Anomabo, Ghana,” PhD diss., (University of Florida, 2010).

_____________________________\\___________________________

Bibliography

Anyim, Daniel. “We Sold Slaves Too: The Disappearance of Anomabo and Fort William In Public Narratives Surrounding The Atlantic Slave Trade,” PhD diss., (Central European University, Budapest, 2020).

Law, Robin. “The Government Of Fante In The Seventeenth Century.” The Journal of African History 54, no. 1 (2013): 31-51. doi:10.1017/s0021853713000054.

Micots, Courtnay. “African Coastal Elite Architecture: Cultural Authentication During The Colonial Period In Anomabo, Ghana,” PhD diss., (University of Florida, 2010).

Micots, Courtnay. “Status and Mimicry.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 1 (2015): 41-62. doi:10.1525/jsah.2015.74.1.41.

_____________________________\\___________________________

Images

(Figure 1) Micots, Courtnay. “Performing Ferocity: Fancy Dress, Asafo, and Red Indians in Ghana.” African Arts 45, no. 2 (2012): 24-35. doi:10.1162/afar.2012.45.2.24.

(Figure 2) Micots, Courtnay. “Status and Mimicry.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 1 (2015): 41-62. doi:10.1525/jsah.2015.74.1.41.

(Figure 3) Micots, Courtnay. “African Coastal Elite Architecture: Cultural Authentication During The Colonial Period In Anomabo, Ghana,” PhD diss., (University of Florida, 2010).

(Figure 4) Micots, Courtnay. “African Coastal Elite Architecture: Cultural Authentication During The Colonial Period In Anomabo, Ghana,” PhD diss., (University of Florida, 2010).

(Figure 5) Micots, Courtnay. “Status and Mimicry.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 1 (2015): 41-62. doi:10.1525/jsah.2015.74.1.41.

(Figure 6) Micots, Courtnay. “Status and Mimicry.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 74, no. 1 (2015): 41-62. doi:10.1525/jsah.2015.74.1.41.

(Figure 7) Rewerts, Ardis M., and Alira Ashvo-Munoz. “Off-Beat Rhythms: Patterns in Kubas Textiles.” The Journal of Popular Culture 32, no. 2 (1998): 27-38. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1998.00027.x.