Founded in 1819, the British colony of Singapore was established as an administrative and trade hub for the Malayan peninsula, intended both to cement a British presence in the region, and create a platform to compete with and contain Dutch influence in the lucrative region. Singapore’s original planning document, The Jackson Plan was drawn between 1822 and 1823 at the behest of Lieutenant-Governor Sir Stamford Raffles, who appointed the plan’s namesake, Lieutenant Jackson to lead the planning committee.1 Built around the Singapore River and founded on ideas of tabula rasa, as well as racial and class segregation, no official document would formally replace it for more than a century. Within the segregated fabric of the 19th c. Jackson Plan for Singapore, migrant Asian and indigenous populations exercised their own agency within the colonial fabric through appropriations of the Rafflesian shophouse, altering it to be a tool and symbol of cultural resilience.

Rooted in colonial notions of European superiority, Raffles’ conceptions of tabula rasa as well as his implementation of a grid system, work to invalidate the site’s indigenous history as well as any following claim to the land. When British settlers arrived, the island was an outpost of the Johor Sultanate,2 the island’s only active populations residing in a small number of fishing villages. As Pieris recounts, the leaders of these communities permitted Raffles’ company to settle the island in return for an agreed upon annual payment of 500 Spanish Dollars, following which the colonists occupied “Bukit Larangan (Forbidden Hill)”, thought to be the site of the 14th century Temasek Palace.3 Raffles would advance his planning and development enabled by flawed concepts of tabula rasa – disregarding the sites indigenous history, and later its habitation. Later he would continue this process of invalidation by imposing a grid over the landscape, a process described by Kostof as follows: “… the grid inscribed the social preeminence of a property-owning class, a kind of territorial aristocracy. The first settlers divided the land and thereby ensured themselves the power to govern the affairs of the city.”4 Through Raffles’ control over the colonial cities organization and habitation patterns, partially via the grid system, he relegated inhabitants who did not meet his criteria of race or wealth to lesser status citizens, forcing them out of the land they previously occupied, often to lower ground and away from freshwater, a result explicitly attested to in Philip Jackson’s plan.

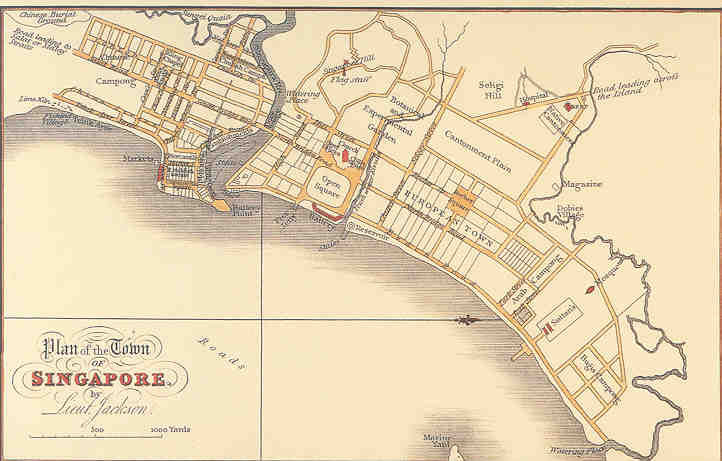

Jackson’s original planning document, explicitly labelling the ethnic and class districts as well as the planned grid.

As a tool to exert control over the settlement’s non-European population, Raffles dictated the plan to segregate groups by ethnicity and class, reserving geographically favourable land for trade and European settlers, forcibly relocating existing communities while simultaneously isolating ethnic groups from each other. This is demarcated in the original labelled plan, and is reflected by Raffles’ explicit letters to the committee, providing detailed instructions regarding the expulsion of populations to specified zones within the developing settlement. Categorizing groups by the broad generalizations employed by the colonizing officials, his letters as only one example displayed naked contempt for the town’s non-mercantile Chinese populace, providing instructions to expel the Chinese community from the waterfront and riverside, to lower ground northeast of the Singapore River, clearing the more easily habitable and river-adjacent land for European settlers and members of the merchant class.5 Similarly dictating the permissible locations of each group recognized by the settler government, his letters illustrate the measure of influence Raffles had over the plan, from ordering the grid’s employment to the degree of specifying dimensions and material within the city’s fabric. Pieris’ examination of the plan concluded that not only did the plan prioritize wealthy classes, it was also intended to isolate ethnic groups to discourage political cooperation and ensure the settler government’s uncontested control.6 However, despite their efforts, Singapore’s marginalized citizens still found ways to express their agency within the constructed environment.

A British surveyor, Thomson’s 1846 idealized painting depicts a vantage point from atop Bukit Larangan, appropriated for colonial use to Government Hill (Contemporaneously Fort Canning Park). The painting looks towards the harbour, over the Singapore River as well as parts of the European and Merchant districts of the town. In the right of the image, blocks of rafflesian shophouses are visible.

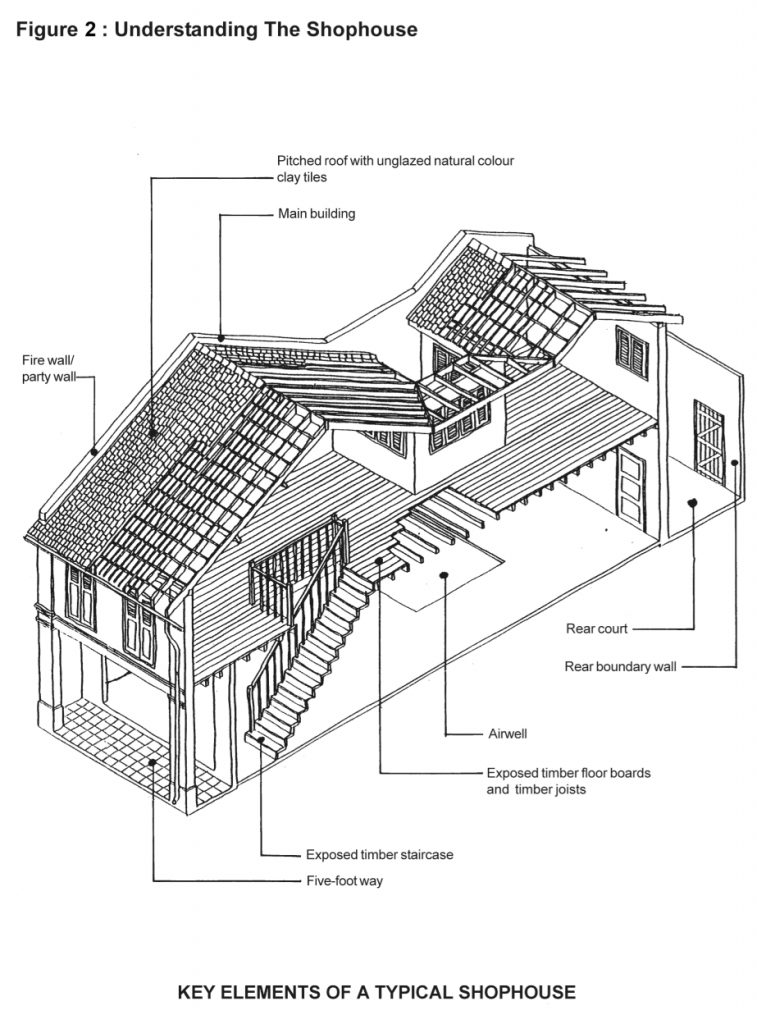

While imposing a Eurocentric perspective over the town’s existing vernacular typologies, Raffles’ ordinances would create disputed space between the shophouse and street, and be appropriated by Singapore’s marginalized populations. Raffles, taking issue with the commonly employed Chinese shophouse typology, mandated in his 1822 letter to Jackson’s committee that all brick and tile houses possess a “uniform type of front” as well that each must have “a verandah of a certain depth, open to all sides as a continuous and open passage on each side of the street,”7 the passages forming a five-foot arcade where the houses formed blocks. Lim, referencing John Thompson’s paintings depicting the results of Jackson’s plan, illuminates that Raffles’ edict was not only made from expressed concerns regarding fire and sanitation, but was borne from the settler’s biased ideals of European “enlightenment”.8 His ordinance resulted in the adaptation of the already-employed Chinese shophouse typology to a new subtype, the “Rafflesian Shophouse”. With the addition of a veranda these shophouses maintained many characteristics of the type imported by Chinese migrants, possessing a narrow streetfront (4.9 m – 5.5 m), and due to the dimensions of the Jackson’s grid plan could extend to 61 m into the block.9 The contradiction between the arcades classification as legally protected private property, and the edict that these spaces remain clear transformed the arcades into intensely contested territory between property owning citizens and the city.10 Presenting an opportunity for marginalized residents to exercise public agency, the spaces were, and continue to be, creatively employed, becoming businesses, extensions of interior space, and storage. However, in 1887 the city attempted to quash these efforts, passing additional legislation to clear the verandas, stating sanitary reasons. In 1888, when the bylaw came into effect, it triggered organized protests where businesses closed in tandem, and concluded in several days of violent riot, following which the legislation was retracted.11 Since their conception as a product of European Enlightenment, Raffles’ five-foot corridors have become both public spaces where marginalized communities can express individual agency, and platforms for successful resistance against colonial law.

Due to a government supported movement to conserve and restore Singapore’s architectural heritage, Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority has published resources regarding restoration efforts. This axonometric section highlights key parts of the building, including Raffles veranda and five-foot way.

Despite Raffles’ requirement for the street fronts of these brick and tile houses to be of a single homogenous type,12 shophouse facades became vehicles reflecting the city’s political condition and the cultural identity of Singapore’s population. Analyzing the facades of Telok Ayer’s shophouses built through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Li noted the slow transition in style that occurred within the region Raffles segregated to Singapore’s Chinese populace. Examining the façade ornament and structure by surface area and ethnic origin, Li diagrammed the chronological appearance of architectural elements, noting that despite the introduction of Tuscan columns in the mid 1820’s the structure and ornament of the shophouse facades remained primarily of Chinese architectural origin, on average composing 51.3% of the façade surface area, with standout examples favouring Malay characteristics.13 While Malay vernacular elements would be quickly adopted by settlers and immigrants alike, later in the 19th century the distinct styles of each district would begin to mix and spread as the Raffles’ segregation scheme began to collapse due to the city’s increasing population. Exacerbated by the increase and subsequent cultural proximity, the Palladian styles introduced by Jackson’s successors, George Coleman and John Thomson, would become widespread.14 Li documenting this shift, notes Telok Ayer’s quick adoption of Malay vernacular elements, as well as the slower, but sustained adoption of European Classical and neutral elements.15

Designed according to the wishes of Singapore’s lieutenant-governor, Thomas Raffles and built on concepts of European enlightenment and tabula rasa, the 1823 Jackson Plan for the Town of Singapore imposed a grid system over the urban fabric, segregating the population by ethnicity and wealth class, manifesting a social hierarchy using the allocation of space and land. However, marginalized populations would appropriate the forms instituted by the plan to express public agency and transform typologies into symbols of resistance against colonial law and power.

Footnotes:

- Teo Siew Eng. “Planning Principles in Pre- and Post Independence Singapore,” The Town Planning Review 63, no.2 (1992): 166.

- Kristina Göransson, “From Temasek to the Republic of Singapore: A Historical Overview,” in The Binding Tie: Chinese Intergenerational Relations in Modern Singapore (University of Hawaii Press, 2009), 19-20.

- Anoma Darshani Pieris, “Hidden Hands and Divided Landscapes: Penal Labour and Colonial Citizenship in Singapore and the Straits Settlements, 1825-1873,” (Doctoral Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 2003), 62.

- Spiro Kostof, A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 140-141.

- Thomas Raffles, “Raffles to Captain C.E. Davis, President, George Bonham, Alex L. Johnston, November 4, 1822.” In The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and East Asia 8, (1854): 101-109.

- Pieris, 62-65.

- Raffles, 107.

- Jon S. H. Lim, “The ‘Shophouse Rafflesia’: An Outline of its Malaysian Pedigree and its Subsequent Diffusion in Asia,” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 66, no. 1 (1993): 49-51.

- Robert Home, “The ‘Warehousing’ of the Labouring Classes,” in Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities (New York and London: Routledge, 2013), 111-114.

- Andrew Harding, “Five-Foot Ways as Public and Private Domain in Singapore and Beyond,” Journal of Property, Planning and Environmental Law 10, no. 1 (2018): 36-55.

- Brenda Yeoh, “The Control of ‘Public’ Space: Conflicts over the Definition and Use of the Verandah,” in Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Urban Built Environment (Singapore: NUS Press, 2013), 250-253.

- Raffles, 107.

- Tze Ling Li, “A Study of Ethnic Influence on the Facades of Colonial Shophouses in Singapore: A Case Study of Telok Ayer in Chinatown,” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 6 no.1 (2007): 41-48.

- Teo Siew Eng and Victor R. Savage, “Singapore Landscape: A Historical Overview of Housing Change,” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 6, no. 1 (1985): 48-53.

- Li, 41-48.

Bibliography:

Eng, Teo Siew. “Planning Principles in Pre- and Post Independence Singapore.” The Town Planning Review 63, no.2 (1992): 163-185.

Eng, Teo Siew, and Victor R. Savage. “Singapore Landscape: A Historical Overview of Housing Change.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 6, no. 1 (1985): 48-63.

Göransson, Kristina. “From Temasek to the Republic of Singapore: A Historical Overview” In The Binding Tie: Chinese Intergenerational Relations in Modern Singapore, 19-31. University of Hawaii Press, 2009.

Harding, Andrew. “Five-Foot Ways as Public and Private Domain in Singapore and Beyond.” Journal of Property, Planning and Environmental Law 10, no. 1 (2018): 36-55.

Home, Robert. “The ‘Warehousing’ of the Labouring Classes. ” In Of Planting and Planning: The Making of British Colonial Cities, 92-122. New York and London: Routledge, 2013.

Jackson, Philip. Plan of the Town of Singapore by Lieut. Jackson. 1823, Urban Planning Document. National Museum of Singapore: Singapore History Gallery, Singapore.

Kostof, Spiro. A History of Architecture: Settings and Rituals. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Li, Tze Ling. “A Study of Ethnic Influence on the Facades of Colonial Shophouses in Singapore: A Case Study of Telok Ayer in Chinatown.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 6 no.1 (2007): 41-48.

Lim, Jon S. H. “The ‘Shophouse Rafflesia’: An Outline of its Malaysian Pedigree and its Subsequent Diffusion in Asia.” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 66, no. 1 (1993): 47-66.

Pieris, Anoma Darshani. “Hidden Hands and Divided Landscapes: Penal Labor and Colonial Citizenship in Singapore and the Straits Settlements, 1825 -1873.” Doctoral Thesis, University of California, Berkeley, 2003.

Raffles, Thomas. “Raffles to Captain C.E. Davis, President, George Bonham, Alex L. Johnston, November 4, 1822.” In The Journal of the Indian Archipelago and East Asia 8, (1854): 101-109.

Singapore Urban Redevelopment Authority. Understanding the Shophouse. 2011. Mixed-Media. Singapore Urban Development Authority, Singapore. https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Get-Involved/Conserve-Built-Heritage/Explore-Our-Built-Heritage/The-Shophouse

Thomson, John Turnbull. Singapore Town from the Government Hill Looking Southeast. 1846.Watercolour on paper, 255 mm x 408 mm. Hocken Pictorial Collections – 92/1217 a12197, Otago University, New Zealand. http://otago.ourheritage.ac.nz/index.php/items/show/4736.

Yeoh, Brenda. “ The Control of ‘Public’ Space: Conflicts over the Definition and Use of the Verandah.” In Contesting Space in Colonial Singapore: Power Relations and the Urban Built Environment, 243-280. Singapore: NUS Press, 2013.