Constructed in a traditional neoclassical architectural style, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is the largest art museum in the United States. The permanent collection consists of works of art and artifacts from ancient Egypt, European masters collections, and an extensive collection of American and modern art. It also maintains holdings of African, Asian, oceanian, byzantine, and Islamic art. It is currently also host to encyclopedic collections of musical instruments, costumes, accessories as well as weapons and armor from around the world. It was founded in 1870 for the purpose of “bringing art and education to the American people”.[1] Arguably there are questions that should be posed surrounding where the objects came from, and on whose authority they are standing there today. Intricate vases sit within the glass casings as visitors walk around them observing like animals in the zoo. There is something eerie about the nature of peering into the cases and seeing everyday household items on display. The power dynamic between the host and represented is maintained. The artifacts and exhibitions hosted at the Metropolitan Museum of Art have a strong cultural importance for the fabric of New York City. As a result of the institutional history of this museum and of New York, there demands a revisitation of the way cultural objects are displayed, and an assessment of the representation of non-white, non-western communities within the institution.

The museum sits right at the edge of New York Cities spectacular Central Park, a luscious green haven in the middle of the bustling urban metropolis. It is a remarkable piece of architecture, and has undergone many expansions over the years which can be seen in the varying architectural styles that appear as you move through it. The current façade and entrance on Fifth Avenue was completed in 1926.[2] As seen in figure 1, the characteristics of neoclassical style are quite apparent. The grandeur of the scale in comparison to the street as well as the dramatic use of Corinthian style columns with a thick stone entablature command a presence along the street. There is also the infamous staircase that leads visitors up off the street level and towards this massive structure, further emphasizing the opulence of the museum.

Figure 1: View of entrance façade on Fifth Avenue at Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City

It is a museum holding artifacts from all over the world, founded under the premise that it would become a space for people to come and be educated and inspired.[3] Its collection was first filled with 174 European paintings from the sixteenth to nineteenth century, and would later expand to include all types of artifacts donated by the men who sat on the museum board.[4] These collections were displayed in a manner that stood as a reminder of the wealth of the donator, and the museum served as an extension of the elite social world of collectors. Rich and powerful men in New York stocked the museum board, all with connections in finance and government.[5] Steven Conn author of Do Museums Still Need Objects? remarks that objects are no longer central to the conception and functions of museums. He outlines the diminished role of objects and how they have started to leave museums.[6] Focusing his discussion on the term “repatriation” and uses the Metropolitan as an example of the artifacts that are now on their way back to their original locale. He states that objects once assumed to have found their place in collections and museums now are relocated.[7] The act of repatriation is not a new phenomenon in the 21st century, and in fact has become a proxy for the larger issue that surrounds the legacy of imperialism and colonialism in modern society. It raises questions about whether or not culture can be owned, and who is the rightful owner of these “objects”. As stated in the New York Times article by Colin Moynhian, the Met over the years has parted with items that are suspected to have been stolen, and returned them. For example in 2017 a 2,300 year old vase that was suspected to have been looted by tomb raiders in Italy in the 1970s was seized and returned to Italy.[8] The question that remains here is how to determine whether these items have been “stolen” and what that definition entails for the items that are deemed to have been achieved by legitimate means.

Figure 2: Showing the display room for the artifacts of the Northern West Coast Indigenous art and woodwork.

The premise of repatriation can be traced back to the UNESCO 1970 convention that challenged the notion that all mankind owns a shared cultural heritage.[9] The document suggested that cultural property belongs in the source country, and that any works that reside in museums abroad are there wrongfully and should be repatriated.[10] The argument should be made that all cultural and intellectual property belongs to the communities from which it originates. However whether all museums are obligated to return these artifacts remains up for contention. There have been attempts by the Metropolitan to shift the purpose from displaying wealth and fortune towards emphasis on education and conservation. Despite this the museum remains stocked with collections of stolen artifacts from all over the world.

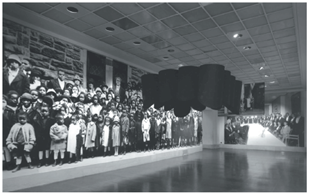

As well as being held accountable for the artifacts within the museums collections, there is a responsibility for the Metropolitan as an institution to assess it’s underrepresentation of minority communities both in the governance of the museum, as well as within its galleries. Harlem on my Mind was an exhibition at the Metropolitan in 1969, which sparked a series of protests resulting from uproar about the decision to exclude African American artists and the Harlem community from an exhibit supposedly about Harlem.[11] This demonstration provided a glimpse into the power dynamic that maintains within institutions such as the Metropolitan since the first days it was constructed. As previously mentioned, it was founded and run by a group of rich white men and this legacy manifests itself in the underrepresentation within the museum today.

Figures 2 and 3: Images from Harlem on My Mind exhibit (1969) at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

In the early years after the 1960s the leaders and aims of the museum began to shift their focus towards public engagement and what was described as “cultural decentralization”.[12] This was a policy that identified the underrepresented communities within the museums reach. Around the 1970s the museum embarked on a community outreach program which focused on cultivating community relationships.[13] Since then, the population has been challenging the Met and other museums to continue to be transparent and reflect more accurately the diversity of the city in which it sits.

The Harlem on my Mind controversy is a small part of New York City’s history with race relations within the art world, and it stands as an example of the lasting effects that colonialism has on institutions within cities. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is but one example of how architecture can become a physical manifestation of these long standing power relationships. Between the cultures being displayed, and those who are in charge of displaying them. Within these institutions there is a desperate need to reassess the structures in place for representation. Both in terms of the rightful owners of this intellectual and cultural property, as well as the representation of the plethora of diverse communities that live and exist in New York city today.

[1] The Metropolitan Musem of Art. Zürich: Met Art Collection, 1986.

[2] Trask, Jeffrey. Things American: Art Museums and Civic Culture in the Progressive Era. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

[3] Cahan, Susan E. “Harlem on My Mind at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Essay. In MOUNTING FRUSTRATION: the Art Museum in the Age of Black Power, 31–106. DUKE University Press, 2018.

[4] Cahan, Susan E. “Harlem on My Mind at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Essay. In MOUNTING FRUSTRATION: the Art Museum in the Age of Black Power, 31–106. DUKE University Press, 2018.

[5] Cahan, Susan E. “Harlem on My Mind at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Essay. In MOUNTING FRUSTRATION: the Art Museum in the Age of Black Power, 31–106. DUKE University Press, 2018.

[6] Conn, Steven. “Whose Objects? Whose Culture? The Contexts of Repatriation.” Essay. In Do Museums Still Need Objects?, 58–85. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.

[7] Conn, Steven. “Whose Objects? Whose Culture? The Contexts of Repatriation.” Essay. In Do Museums Still Need Objects?, 59. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.

[8] Nyt article https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/15/arts/design/met-museum-stolen-coffin.html

[9] Scott, David A. “Modern Antiquities: The Looted and the Faked.” International Journal of Cultural Property 20, no. 1 (2013): 49–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0940739112000471.

[10] Conn, Steven. “Whose Objects? Whose Culture? The Contexts of Repatriation.” Essay. In Do Museums Still Need Objects?, 59. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.

[11] Cotter, Holland. “What I Learned From a Disgraced Art Show on Harlem.” The New York Times. The New York Times, August 19, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/20/arts/design/what-i-learned-from-a-disgraced-art-show-on-harlem.html.

[12] Conn, Steven. “Whose Objects? Whose Culture? The Contexts of Repatriation.” Essay. In Do Museums Still Need Objects?, 42. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.v

[13] Conn, Steven. “Whose Objects? Whose Culture? The Contexts of Repatriation.” Essay. In Do Museums Still Need Objects?, 42. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.v

Bibliography

Cahan, Susan E. “Harlem on My Mind at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” Essay. In MOUNTING FRUSTRATION: the Art Museum in the Age of Black Power, 31–106. DUKE University Press, 2018.

Conn, Steven. “Whose Objects? Whose Culture? The Contexts of Repatriation.” Essay. In Do Museums Still Need Objects?, 42. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010.v

Cotter, Holland. “What I Learned From a Disgraced Art Show on Harlem.” The New York Times. The New York Times, August 19, 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/20/arts/design/what-i-learned-from-a-disgraced-art-show-on-harlem.html.

Scott, David A. “Modern Antiquities: The Looted and the Faked.” International Journal of Cultural Property 20, no. 1 (2013): 49–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0940739112000471.

Trask, Jeffrey. Things American: Art Museums and Civic Culture in the Progressive Era. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013.

The Metropolitan Musem of Art. Zürich: Met Art Collection, 1986.

Images:

Hilburg, Jonathan. “The Met Premieres an Annual Facades Series to Spotlight Contemporary Work.” The Architect’s Newspaper, August 19, 2020. https://www.archpaper.com/2019/03/met-premiers-annual-facades-art-series/.

metmuseum.org. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/online-features/met-360-project.