A relic of Thai architecture untouched by colonial influence

Wat Phra Kaew

The history of Wat Phra Kaew is inextricably entangled in the history of Thailand itself. The building’s lack of colonial architectural influence is a rarity in southeast Asia for buildings of the same era and can be tied to the lack of colonial influence on the whole of Thailand at the time. This makes the story of Wat Phra Kaew inseparable from the history of Thailand’s monarchy and especially how it, as country, was able to avoid full colonial rule, unlike many of its direct neighbours. However, the progression of building at the complex of Thailand’s royal palace show the inescapable reach of colonial influence in the subsequent dynasties after Wat Phra Kaew’s construction.

This entry focuses on the political and cultural framework of Thailand at the turn of the 18th century that led to Wat Phra Kaew’s construction, including the influence and attempted erasure of the previous seat of power at Thailand’s old capital of Ayuttaya. The entry goes on to examine the how the progression of rulers in the Chakri Dynastic line became increasingly influenced by outside powers and how these changes were reflected in the additions made at Wat Phra Kaew and the greater complex. This is tied back to Michael Herzfeld’s concept of “crypto-colonialism”, exemplifying how even Thailand, being “free” from colonial rule came to adopt Western building conventions in years subsequent to Wat Phra Kaew and how the temple stands now as a rare and unique example of unadulterated Thai architecture.

The Emerald Buddha

The name Wat Phra Kaew literally translates to Temple of the Emerald Buddha in English and it is impossible to fully grasp the significance of the temple itself without first understanding the Buddha image for which it is named.

The Emerald Buddha is carved from a single piece of stone, likely either jadeite or nephrite, though its religious significance has prevented any scientific exploration of its exact mineral composition to date1. The image of the Buddha is depicted with legs crossed and hands in a meditative pose wearing the sanghati, a typical unadorned monk’s robe.

While the iconography of the Buddha image is unremarkable when compared to the many other figural representations of the Buddha, its history and chronicle have led to its veneration as the most important and sacred image of Buddha in Thailand’s history. The legend states that it was the first image of the Buddha ever made, around 500 years after buddha’s death2. The statue was first historically documented in 1434 CE, at a temple in Northern Thailand when lightning supposedly struck a chedi, cracking it open to reveal, hidden inside, a statue of buddha covered in stucco or possibly gilt. As the outer coating flaked off, it is said, the emerald buddha interior was revealed3.

The statue was then moved from city to city within Thailand and out of the country, changing hands as wars were fought and cities sacked. The Buddha made its way throughout Southeast Asia from Laos to Myanmar and finally back to Thailand, Siam at the time, in the hands of King Sukhothai whose island capital of Ayuttaya sat around one-hundred kilometers North of Bangkok4. Here, the Emerald Buddha stayed until the sacking of Angkor when King Rama I took power over Thailand, beginning the Chakri dynasty, which still rules today. It was under this dynasty that Bangkok was established as the new capital and Wat Phra Kaew and the great palace complex in which it stands was constructed5.

1Melody, Rod-Ari, “Visualizing Merit: An Art Historical Study of the Emerald Buddha and Wat Phra Kaew.”. (PhD diss., University of California, LosAngeles, 2010).

2Robert E. Bushnell, “Phra Kaew Morakot” in The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism (Princeton University Press, 2014), 642.

3 Joseph Bushnell Ames, The Emerald Buddha. (Massachusetts: Small, Maynard, 1921), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433043250418&view=1up&seq=1.

4 Francis D.K. Ching, et al., “Wat Phra Kaew” in A Global History of Architecture, (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017) 613-614. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=4833697.

5 Melody, Rod-Ari, 2010

The Royal Palace Complex and Wat Phra Kaew

Construction of the Royal palace complex began in 1782, on the east bank of the Chao Phraya river, with a religious compound of four buildings, including Wat Phra Kaew, and the royal palace itself. More buildings were added over the centuries throughout the Chakri dynasty as the duties of the royal family evolved. These additions including larger palace residences to accommodate the King’s many wives and children, meeting halls, ceremony halls and military and administrative offices1. The Northeastern section of the complex being reserved for the religious buildings including Wat Phra Kaew.

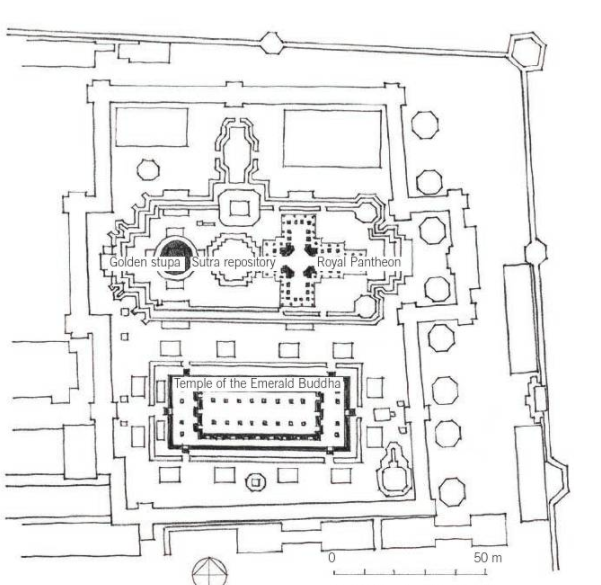

Within this compound are four main religious buildings, three on the northern platform, from east to west the Golden Stupa, Sutra Repository and the Royal Pantheon and to the South, Wat Phra Kaew.

The Golden Stupa, true to its name, is encased completely in a layer of gold, housing one of the major relics of the Buddha2, while the other two structures are clad in mosaic and mirrored tile like that of Wat Phra Kaew.

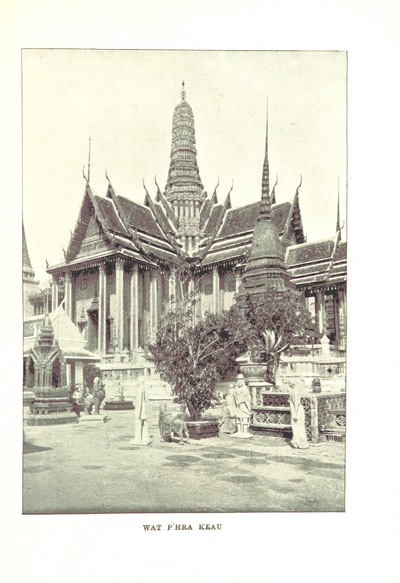

On the Southern platform is temple of the Emerald Buddha, outlined by a continuous rectangular colonnade projecting east and west. The temple’s tall mosaiced columns support a massive three tiered roof of orange, yellow and blue glazed tiles.

The gilded pediments depict the Hindu god Vishnu riding on the back of the mythical bird-man Garuda and the base of the temple is continuously ringed by a line of one hundred and twelve protective Garudas3. The temple comprises a single, undivided interior space with the Emerald Buddha located at the far end and raised high above the ground in a small, golden temple structure.

Above the Buddha’s head is a nine tiered umbrella, a symbolic honour reserved only for the king, with a ceiling of iridescent blue tile, and the marble platform on which it stands is protected by more statues of Garuda, this time holding Nagas or guardian cobras in hand4.

Wat Phra Kaew is significant in its lack of monastic residences, an uncommon feature for Buddhist temples, which generally serve as a residence for the monks who maintain them. As it is located in a compound on the grounds of the royal palace, the temple instead serves as the place where the king of Thailand is able to perform his ceremonial religious duties5. These include the ceremonial changing of the Emerald Buddha’s garments each season from a ceremonial robe in summer, to monastic robes in the rainy season and finally a mantle of gold beads in the cold season6 (see Figure 1).

The interior of Wat Phra Kaew is painted with frescoes of important religious stories including depictions of the funeral rites of many royal family members7. The structural trusses are of wood, and the exterior is decorated with with mosaic ceramic and mirrored tiles8.

1Melody, Rod-Ari, “Visualizing Merit: An Art Historical Study of the Emerald Buddha and Wat Phra Kaew.”. (PhD diss., University of California, LosAngeles, 2010).

2 Joseph Bushnell Ames, The Emerald Buddha. (Massachusetts: Small, Maynard, 1921), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433043250418&view=1up&seq=1.

3Robert E. Bushnell, “Wat Phra Kaew” in The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism (Princeton University Press, 2014), 991.

4Francis D.K. Ching, et al., “Wat Phra Kaew” in A Global History of Architecture, (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017)613-614. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=4833697.

5 Joseph Bushnell Ames, 1921.

6Robert E. Bushnell, “Phra Kaew Morakot” in The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism (Princeton University Press, 2014), 642.

7Pattaratorn Chirapravati, “Funeral Scenes in the Rāmāyaṇa Mural Painting at the Emerald Buddha Temple.” In Materializing Southeast Asia’s Past: Selected Papers from the 12th International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, Ed. Marijke Klokke and Veronique Degroot, (2013) 221-232. Accessed Feb 12, 2021. https://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/895506.

8Francis D.K. Ching, et al., 2017.

Architectural Inspirations and Influence

As Thailand was never fully-colonized, unlike many of its neighbours, the rulers had a greater freedom to explore and develop a unique architectural style. This included fusing elements of inspiration from many cultures much more freely than their counterparts1. While scholars appear to disagree to what extent western imperialism had an effect on the architectural traditions of Thailand, it is apparent in the example of Wat Phra Kaew that a fusing of cultures was being accepted and triumphed in the eyes of at least it’s patron King Rama I.

Much of the temple’s initial Thai influence comes from the original capital of Ayutthaya, whose designers and craftspeople were employed by King Rama I to build the new royal palace complex in Bangkok2. As a result, many of the same materials such as wood, brick and laterite were transported from the old capital to build the new one. This may have been King Rama I’s way of symbolically linking his new capital to the old one or simply out of convenience of available materials. However, this decision likely had had more to do with the intended physical erasure of the past dynasty in a bid to secure full political power. Little remains of the original buildings at Ayutthaya due this removal of materials.

The temple also draws inspiration from Khmer architectural traditions of the prasat, a Hindu symbol used by kings to signify that they had the Mountain of Meru under their domain3. The prasat at Wat Phra Kaew is the large finger-like spire with rounded peak rising from the centre of the temple roof.

The inclusion of Hindu artwork and religious stories are also present on the rectangular colonnade that rings the complex. A continuous depiction of one-hundred and seventy eight murals retelling the sacred Hindu story of Ramayana are painted there4.

It is not uncommon to see Hindu and Buddhist stories and architectural elements represented in Thai temples. The Thai kings were thought of as representatives of the god Rama and would act as spiritual and physical protector of the people of Thailand supporting both Buddhism and Hinduism5. The Rein of Rama I was characterized by “cosmopolitan literary tastes”6, wherein many literary works were being translated from other languages to Thai. Among these were the Ramayana, Ramakien in Thai, which involves the monkey-god Hanuman fighting the forces of evil7. This became a popular story to be retold in artworks from paintings, to shadow puppetry to classical dance, likely further leading to its incorporation by King Rama I within the royal palace temple grounds8 .

1Francis D.K. Ching, et al., “Wat Phra Kaew” in A Global History of Architecture, (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017)613-614. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=4833697.

2 Melody, Rod-Ari, “Visualizing Merit: An Art Historical Study of the Emerald Buddha and Wat Phra Kaew.”. (PhD diss., University of California, LosAngeles, 2010).

3 Melody, Rod-Ari, 2010.

4Francis D.K. Ching, et al., 2017.

5Pattaratorn Chirapravati, “Funeral Scenes in the Rāmāyaṇa Mural Painting at the Emerald Buddha Temple.” In Materializing Southeast Asia’s Past: Selected Papers from the 12th International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, Ed. Marijke Klokke and Veronique Degroot, (2013) 221-232. Accessed Feb 12, 2021. https://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/895506.

6 David K. Wyatt, Thailand: A Short History. 2nd ed. (New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2003).

7Francis D.K. Ching, et al., 2017.

8Pattaratorn Chirapravati, 2013.

Changes throughout the Chakri Dynasty

Little was added to the palace and temple grounds during the second Chakri reign of King Rama the II. Though the king’s love for Chinese artistic traditions of the Qing dynasty influenced major additions to the temple by his son King Rama III. The coloured ceramic tiles which adorn the exterior of the temple were added during the third reign and contain Chinese motifs including lion dogs and Mandarin guardians1. The inclusion of these Chinese stylistic embellishments added to the innovative style of the temple and were continued in subsequent generations and other buildings at the palace.

Cambodian style was also a very powerful inspiration for many Thai religious buildings. This is epitomized by the addition of a stone scale model of the Cambodian temple complex of Angkor Wat on the on the Northern platform2. The model was added during the reign of Rama IV who was heavily inspired by the Hindu temple of Angkor Wat. He even asked his armies to transfer the entire structure from Cambodia to Bangkok, though after descriptions of its immensity were recounted, he settled for the construction of a scale model instead3.

In Hindu belief, the temple is a physical representation of the cosmos and therefore a model is seen as equivalent in significance to the primary source4. The model can also be seen as a demonstration of military might as King Rama IV was interested in establishing Thailand as a dominant power in the eyes of the King of France and Queen of England5. This was likely to show cultural authority over the people of Angkor in the frame of colonization, revealing how the immense reach and power of colonial countries was becoming a source of envy for the Thai monarchy. Rama the IV’s obsession with colonial powers led him to hire English tutors to school his heir in English, mathematics and Western history. The king even sent many of his younger sons abroad to be schooled in various countries around Europe, visiting them often.

1Melody, Rod-Ari, “Visualizing Merit: An Art Historical Study of the Emerald Buddha and Wat Phra Kaew.”. (PhD diss., University of California, LosAngeles, 2010).

2Francis D.K. Ching, et al., 2017.

3 Melody, Rod-Ari, 2010.

4Francis D.K. Ching, et al., 2017.

5 Melody, Rod-Ari, 2010.

“Crypto-Colonialism” and Western Influence

By the time Rama V took power, Western culture was being embraced by the monarchy, influencing stylistic tastes and unlike other Southeast Asian countries who had been forced to conform to European colonial forms of architecture, Thailand began to do so voluntarily1. Michael Herzfeld coins this process as “crypto-colonialism” whereby a combination of admiration and resentment of powerful Western nations, leads to a “voluntary” adoption of colonialist ideals2. During the reign of Rama V, many colonial-inspired buildings were added to the complex including the neo-palladian style government house, though Wat Phra Kaew remained almost untouched. Cosmetic additions such as Italian statues were added at the base of the Emerald Buddha’s throne, though the main building retained its Thai, Cambodian, Khmer and Chinese influences.

While Thailand was never colonized in an official sense, the temple of Wat Phra Kaew symbolizes a unique time in the Thai architectural tradition during the end of the 18th century before “crypto-colonialism” had taken hold. During the 19th and into the 20th century Thailand began to fully adopt western influences into their designs, a progression which is apparent in the timeline of construction at the royal palace complex. Being one of the first religious buildings constructed after the fall of Ayuttaya, Wat Phra Kaew provides a unique insight into the Thai architectural tradition before the influence of colonial style. This included inspiration of Khmer, Cambodian, Hindu and even Chinese architectural features. After the fall of the absolute monarchy in 1932, the symbolic seat of power was moved to Wat Phra Kaew, signalling the end of the Chakri dynasty’s absolute control and perhaps solidifying the temple as a memorial to the institution of Thai kingship in general. Today, any efforts put into the temple are done so in the interest of restoration and preservation, leaving the building as a figurative time capsule to a lost dynastic power.

1Melody, Rod-Ari, “Visualizing Merit: An Art Historical Study of the Emerald Buddha and Wat Phra Kaew.”. (PhD diss., University of California, LosAngeles, 2010).

2Michael Herzfeld, “Thailand in a Larger Universe: The LingeringConsequences of Crypto-Colonialism,” The Journal of Asian Studies 76, no. 4 (November 2017): 887–906. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/6C768C696CB19FDB83E7895BAC039592/S0021911817000894a.pdf/div-class-title-thailand-in-a-larger-universe-the-lingering-consequences-of-crypto-colonialism-div.pdf.

Bibliography

Ames, Joseph Bushnell. 1921. The Emerald Buddha. Massachusetts: Small, Maynard [c1921]. Accessed Feb 12, 2021. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433043250418&view=1up&seq=1.

Buswell, Robert E. “Wat Phra Kaew”. In The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 991-991. Princeton University Press, 2014. Accessed Feb 12, 2021. https://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/1389861

Buswell, Robert E. “Phra Kaew Morakot”. In The Princeton dictionary of Buddhism, 991-991. Princeton University Press, 2014. Accessed Feb 13, 2021. https://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/1389861.

Chirapravati, Pattaratorn. “Funeral Scenes in the Rāmāyaṇa Mural Painting at the Emerald Buddha Temple.” In Materializing Southeast Asia’s Past: Selected Papers from the 12th International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, edited by Marijke Klokke and Veronique Degroot, 221-232. NUS Press Pte Ltd., 2013. Accessed Feb 12, 2021. https://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/895506.

Ching, Francis D. K., Jarzombek, Mark M., and Prakash, Vikramaditya. “Wat Pra Kaew.“ In A Global History of Architecture, 613-614. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017. Accessed Feb 12, 2021. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=4833697.

Herzfeld, Michael. “Thailand in a Larger Universe: The LingeringConsequences of Crypto-Colonialism”. The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 76, No. 4 (November 2017): 887–906. Accessed Feb 12, 2021. https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/6C768C696CB19FDB83E7895BAC039592/S0021911817000894a.pdf/div-class-title-thailand-in-a-larger-universe-the-lingering-consequences-of-crypto-colonialism-div.pdf.

Rod-Ari, Melody. “Visualizing Merit: An Art Historical Study of the Emerald Buddha and Wat Phra Kaew.” University of California, Los Angeles, 2010. Accessed Feb 12, 2021. fhttps://search.proquest.com/docview/814730529?pq-origsite=summon.

Wyatt, David K. 2003. Thailand: A Short History. 2nd ed. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press.

Figures

Figure 1: V. R. Sasson, “Tales of the Emerald Buddha: Simplicity and Splendor” Buddhistdoor Global, June 18, 2019. Accessed Feb 12, 2021. https://www.buddhistdoor.net/features/tales-of-the-emerald-buddha-simplicity-and-splendor.

Figure 2: Francis D.K. Ching, et al., “Wat Phra Kaew: Fig. 16.12 Site Plan of Wat Phra Kaew” in A Global History of Architecture, (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017)613-614. Accessed Feb 12, 2021. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ubc/reader.action?docID=4833697.

Figure 3: The British Library. “Bangkok from “Siam: On the Meinam from the Gulf to Ayuthia. Together with Three Romances Illustrative of Siamese Life and Customs with Fifty Illustrations.” Sampson Low & Co., 1897. Accessed Feb 15, 2021: https://www.europeana.eu/en/item/9200387/BibliographicResource_3000117297430.

Figure 4: Dr. Melody Rod-ari, “The Emerald Buddha and pandemics,” in Smarthistory, January 5, 2021, accessed February 16, 2021, https://smarthistory.org/emerald-buddha/.

Figure 5: Pattaratorn Chirapravati, “Funeral Scenes in the Rāmāyaṇa Mural Painting at the Emerald Buddha Temple: Figure 17.11” In Materializing Southeast Asia’s Past: Selected Papers from the 12th International Conference of the European Association of Southeast Asian Archaeologists, Ed. Marijke Klokke and Veronique Degroot, (2013) 221-232. Accessed Feb 12, 2021. https://muse.jhu.edu/chapter/895506.

Figure 6: Eric Lim, “Government House Bangkok: the Palace of Gold” Tour Bangkok Legacies, Accessed Feb 12, https://www.tour-bangkok-legacies.com/government-house.html.

Featured Image: “Wat Phra Kaew, Temple of Emerald Buddha, Bangkok, Thailand”, Wikimedia free media commons. 2 June 2, 2019. Accessed Feb 16, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%E0%_Wat_Phra_Kaew,_Temple_of_Emerald_Buddha,_Bangkok,_Thailand.jpg