Introduction

The Caribbean is a region historically notable for its legacy of colonization and slave labour. As early as the 16th century enslaved Africans were shipped to islands in the West Indies to work on plantations owned and operated by Europeans. In particular, France claimed a substantial amount of territory for its monarchy, and took control of the island today known as Haiti. Haiti, which was at that time known as Saint-Domingue, was saturated with a combination of official French architecture in the style of baroque classicism alongside improvised vernacular architecture that responded to the needs of the average population. After the Haitian Revolution and expulsion of French colonists, these two styles became even more blended. The best example of this merger in style is the Palace of Sans-Souci, which combined elements of baroque classicism with a uniquely Haitian influence. It’s construction and occupation is fundamental to a narrative characterized by the liberation of enslaved Africans, and the struggle for sovereignty as a nation disconnected from imperial Europe.

Haitian Revolution

In the final years of the 18th century, a significant shift in Europe’s influence over its colonies in the West Indies took place. Beginning in 1791 and ending in 1804, the Haitian Revolution was a war for independence fought between French colonists and the African slaves charged with growing and harvesting sugar on what was then called Saint-Domingue. Remarkably, this conflict is the only example of successful uprising by enslaved Africans fighting for their own liberation; one that led to the establishment of an independent state known today as Haiti. The years that followed the revolution were volatile, with the newly liberated Haitians conflicting with one another over who would lead their new nation. Regardless, the transfer of power from colonizers to former slaves in Haiti was a deeply significant cultural, political event that altered perceptions of slavery around the globe.1 One of the key figures of the revolt was a leader named Henri Christophe. Under the leadership of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Christophe participated in significant strategic planning and execution of events crucial to the success of the revolt. After their successful expulsion of the French, Christophe and fellow general Alexandre Pétion staged a coup d’etat, executing their former leader Dessalines and seizing power for themselves. Following these events in 1811, Christophe claimed the northern section of the island as his own kingdom and continued to war against Pétion who ruled in the south. As a leader during and after the revolution, Christophe oversaw the construction of fifteen fortresses, the major example being Citadelle Laferrière; now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Additionally he built nine palaces and reconstituted fifteen plantations as royal chateaux, among these is the most notable Palace of Sans-Souci, located in the hills near the former plantation of Milot.2

Architecture in the French Atlantic

The official architectural style of Saint-Domingue was heavily saturated with forms and influences paying respect to the French monarchy. This official architecture included churches, government buildings and costly private buildings, and did more to acknowledge French domination than to adapt to the environmental, practical requirements of life in the Carribean. These buildings would have been characterized by an organized, so-called rational arrangement of space derived from classical Greek building but with superficial embellishments meant to flaunt the wealth and excess of French power. Unlike vernacular buildings, this architecture employed the use of expensive materials such as stone and masonry and often stood multiple stories towering over neighbouring buildings. This combination of qualities, which came to be known as baroque classicism, characterized the architecture of French colonies globally and served as a symbol for French occupation as well as a means to regulate and control the behaviours of the indigenous and the enslaved.3

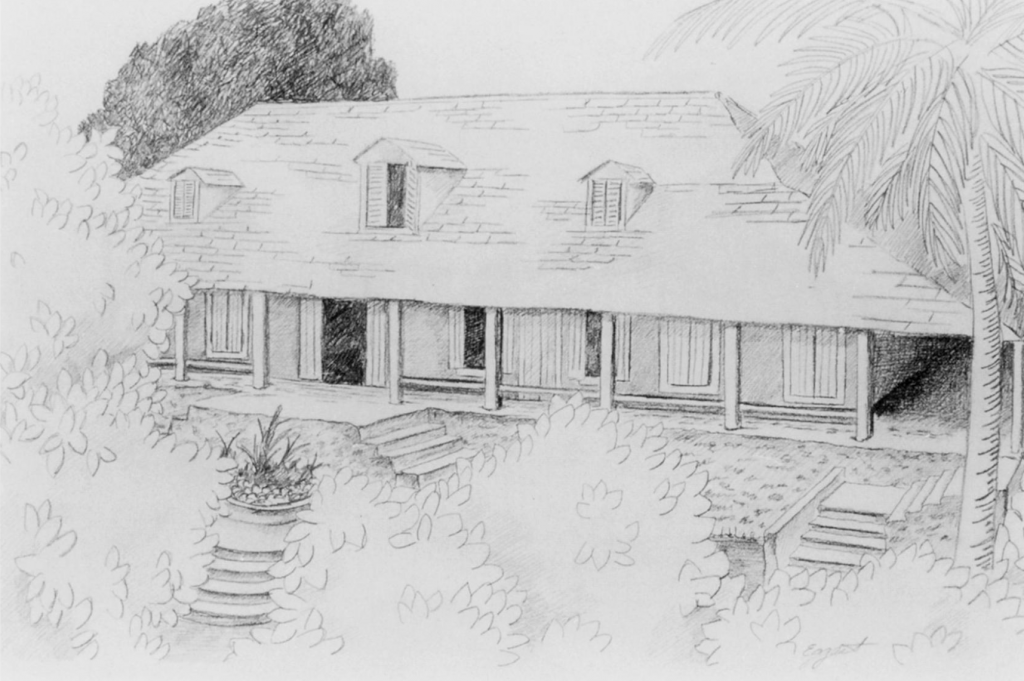

Comparatively, the vernacular architecture of the region, which made up the majority of buildings, reflected less of a European influence. While there was still a geometric organization to the buildings footprint and interior space, buildings were often raised off the ground on pilotis to manage humidity and were free of the excessive baroque stylings that characterized more expensive colonial architecture. Made up of a timber frame structure infilled with grass and mud, these modest yet sophisticated designs were representative of common buildings found in Haiti’s major settlements. Subsequent to the successful uprising of slaves in Saint-Domingue and the expulsion of French colonists, the boundary between French architecture and a new non-French style began to deteriorate.4

Sans-Souci

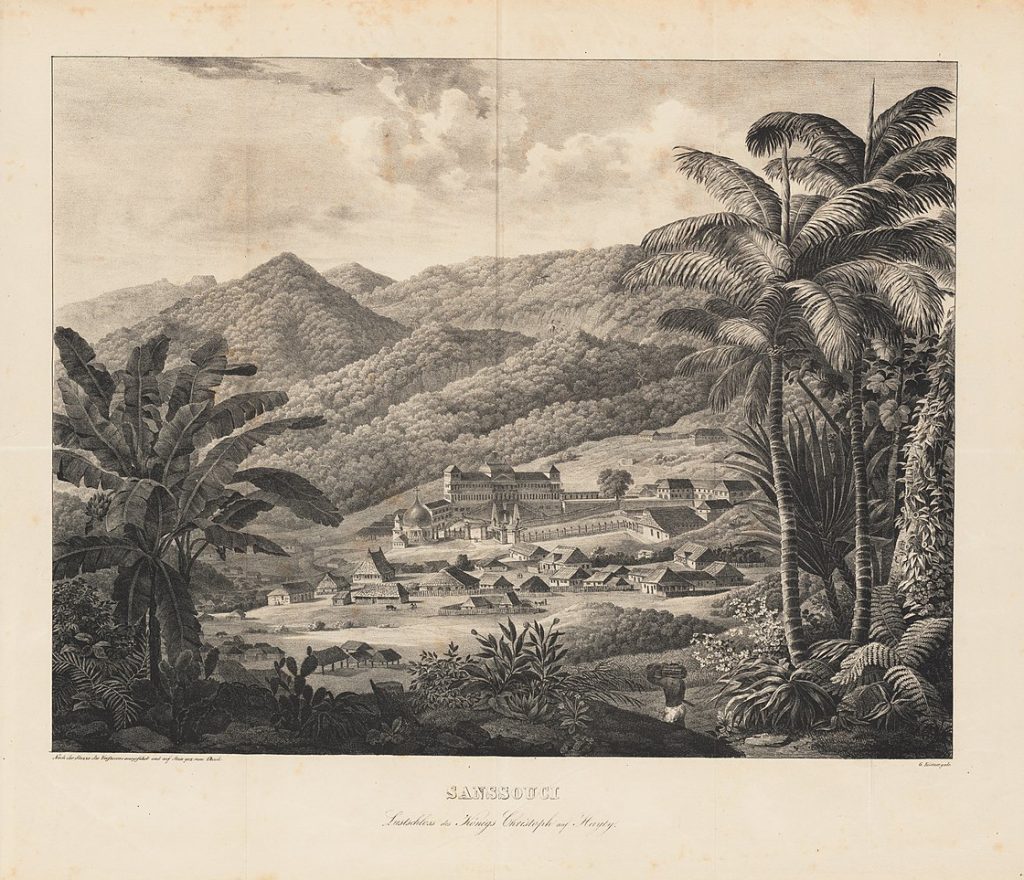

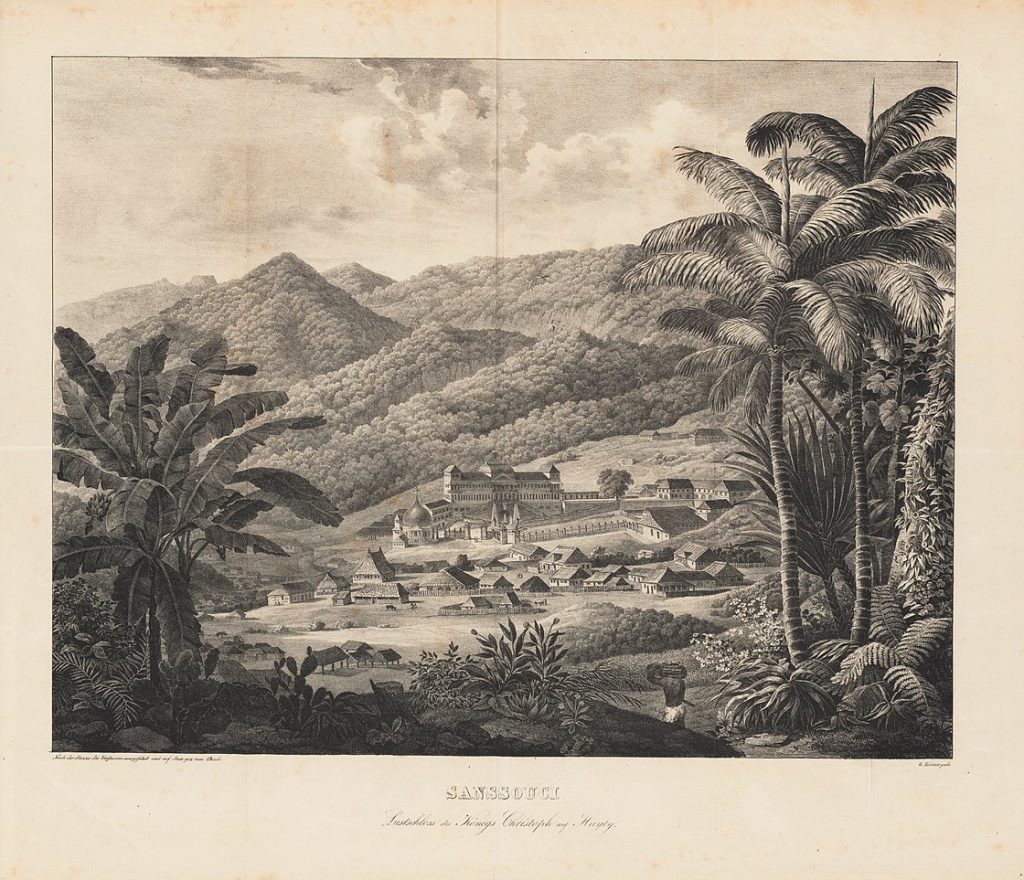

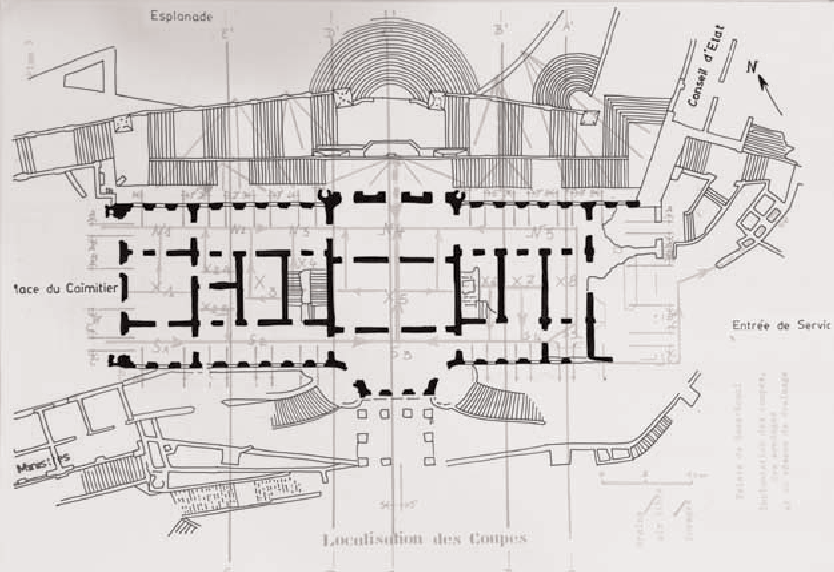

One of the most notable buildings constructed after the Haitian Revolution is the Palace of Sans-Souci, overseen by King Henri Christophe and intended to demonstrate his power and taste as leader of this independent state. Located on a relatively remote hillside near the former plantation town of Milot, Sans-Souci was constructed over a three-year period between 1810-1813. The palace was Christophe’s main place of residence, and sat as the centrepiece to a sprawling compound of structures. Notable buildings included the government offices for the Council of State and the Chamber of Ministers, Champs de Mars; the military barracks and training ground, and the Church of the Pantheon, a memorial housing the remains of heroes who fought and died during the Haitian Revolution.5 Tales of it’s time suggest that here he hosted lavish parties and feasts in celebration of his own power amidst a liberated Haiti. Christophe spared no expense in the realization of this opulent architectural vision and beyond the cost in gold, many labourers died during its construction.

Departing from the vernacular and official French architecture in the region, much of which was destroyed during the revolt, Sans-Souci incorporated some recognizable elements of the French style. Of significant note is the visible nod to Greek revival, popularized by the French in their baroque classical building style. Facing the public was a grand entrance visible from the village of Milot to the north. It featured a pair of grand staircases leading up to the opening above a fountain framed by massive stone buttresses either side of a triumphal arch. Upon reaching the top of the stair, a Doric hexastyle propylaeum with an entablature composed of complex metopes and dentils led into the building; this positioned Christophe with a view over his domain. On either side of the entrance were substantial wings of the building characterized by simple round arches, each of these wings leading to a three-story tower. On the opposite side, the south-facing elevation was identifiable less for its ornate detailing and more for its formal expression. The facade employed a series of shallow pilasters topped with a curved pediment that had small dentils. It featured numerous curved staircases leading down to the stepped gardens below, and is described as a more intimate, and less ominous view of the architecture.6 Each of the wings to the east and west featured outdoor courts with manicured gardens; both of these areas offered expansive views of both the compound and its activities and the hills surrounding Sans-Souci.

Ritter, Naturhistorische Reise nach der westindischen Insel Hayti: Auf Kosten Sr. Majestät des Kaisers von Oesterreich [Stuttgart: Hallberger, 1836]).

(illustration in Carl Ritter, Naturhistorische Reisenach der westindischen Insel Hayti: Auf Kosten Sr.Majestät des Kaisers von Oesterreich [Stuttgart:Hallberger, 1836]).

Critics of Henri Christophe called the palace a poor rendition of superior European precedents, while others declared it akin to a cotton factory, effectively denying the possibility that former slaves could create something beyond their understanding of labour.7 Christophe’s secretary, Baron de Vastey viewed Sans-Souci as an achievement beyond the emulation of European styles, and an advancement on the architecture of the colonies made possible only by the formerly enslaved:

“This year we witnessed the completion of the palace of Sans Souci, and the royal church of that town. These two structures, erected by the descendants of Africans, show that we have not lost the architectural taste and genius of our ancestors who covered Ethiopia, Egypt, Carthage, and Old Spain, with their superb monuments.”8

It’s clear that Christophe’s grand palace represented different things to different people. However stylistically there is no question that Sans-Souci is beyond categorization. Its design employs a diverse set of references to European colonial architecture, but does well to separate itself into a class of its own.

Conclusion

In the years after the revolution, the politics of Haiti were ripe with tumultuous conflict. The rise of Henri Christophe as king of the northern region was accompanied by the rapid development and reclamation of unique post-revolution architecture. Sharing attributes of conventional European styles, but adapted to Haitian life and politics, the Palace of Sans-Souci is the best example of this architecture. It was an imitation of its colonial predecessors, but one that undermined the power dynamic in the French Atlantic and demonstrated the new power of the liberated slaves of Haiti.9 Christophe ruled his kingdom from this palace until his suicide in 1820, after which the palace became the home of multiple conflicts and would-be rulers until its partial destruction in 1843 caused by an earthquake. During the 20th century the ruins of Sans-Souci were given status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and to this day serve as a reminder of the nation’s identity and its historical status as a unique example of slave-led revolution.

Notes

- Dubois, Laurent. Avengers of the New World: the Story of the Haitian Revolution. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005. p. 6

- Monroe, J. Cameron. “New Light from Haiti’s Royal Past: Recent Archaeological Excavations in the Palace of Sans-Souci, Milot.” Journal of Haitian Studies 23, no. 2 (2017): p. 6

- Bailey, Gauvin A. Architecture and Urbanism in the French Atlantic Empire: State, Church, and Society, 1604-1830. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2018. p. 6

- Bailey. p. 16

- Minosh, Peter; Architectural Remnants and Mythical Traces of the Haitian Revolution:Henri Christophe’s Citadelle Laferrière and Sans-Souci Palace. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 1 December 2018; 77 (4): p. 416

- Minosh. p. 419

- Mackenzie,Charles. Notes on Haiti, Made during a Residence in That RepublicLondon: H. Colburn and R. Bentley, 1830,1:170.

- Pompée-Valentin Vastey, Baron de, An Essay on the Causes of the Revolutionand Civil Wars of Hayti, Being a Sequel to the Political Remarks upon CertainFrench Publications and Journals Concerning Hayti, trans. W. H. and M. B.Exeter: Western Luminary Office, 1823, 137.

- Minosh. 424

Bibliography

Bailey, Gauvin A. Architecture and Urbanism in the French Atlantic Empire: State, Church, and Society, 1604-1830. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2018.

Dubois, Laurent. Avengers of the New World: the Story of the Haitian Revolution. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005. https://hdl-handle-net.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/2027/heb.31944. EPUB.

Edwards, Jay D. “The Origins of Creole Architecture.” Winterthur Portfolio 29, no. 2/3 (1994): 155-89. Accessed February 16, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1181485.

Leconte, Vergniaud. Henri Christophe dans l’histoire d’Haiti. Paris: Berger-Levrault,1931.

Mackenzie,Charles. Notes on Haiti, Made during a Residence in That RepublicLondon: H. Colburn and R. Bentley, 1830,1:170.

Minosh, Peter; Architectural Remnants and Mythical Traces of the Haitian Revolution:Henri Christophe’s Citadelle Laferrière and Sans-Souci Palace. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 1 December 2018; 77 (4): 410–427. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2018.77.4.410

Monroe, J. Cameron. “New Light from Haiti’s Royal Past: Recent Archaeological Excavations in the Palace of Sans-Souci, Milot.” Journal of Haitian Studies 23, no. 2 (2017): 5-31. doi:10.1353/jhs.2017.0015.

Pompée-Valentin Vastey, Baron de, An Essay on the Causes of the Revolutionand Civil Wars of Hayti, Being a Sequel to the Political Remarks upon CertainFrench Publications and Journals Concerning Hayti, trans. W. H. and M. B.Exeter: Western Luminary Office, 1823.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 2015. https://hdl-handle-net.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/2027/heb.04595. EPUB.