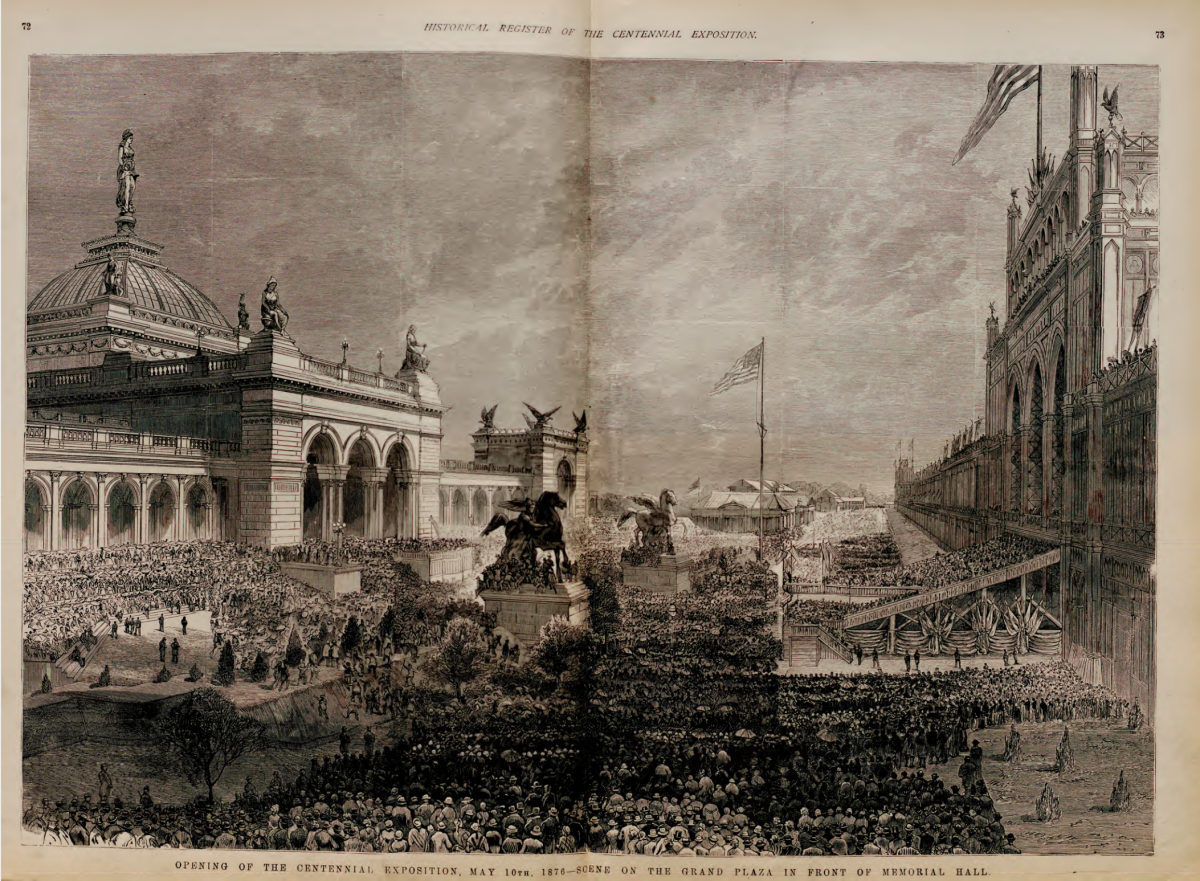

The International Exhibition of Arts, Manufactures, and products of Soil and Mine – referred to as the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 – proudly highlighted the United States’ advancements and achievements, featuring its ability to reunite and resurrect after the American Civil War, but also acted as an “effort to lift the country out of a crippling economic depression.”[1] As an acknowledgement to the past, this Exposition was held in Philadelphia, marking the one hundredth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia. However, the sense of celebration and achievement that dominated the Exhibition neglects and negates the voices of others. The white American perspective of their own achievements, innovations, and advancements at the Centennial Exposition of 1876 undermines and misconstrues the mistreatment and misrepresentation of the African and African American community.

Inequality regarding black representation stemmed from conditions outside of the fairgrounds, however, were reflected in similar ways within the confines of the Exhibition. “This stinging rebuff would also serve as a solemn reminder to black Americans that, ten years after [losing] the shackles of enslavement, the freedoms and privileges guaranteed with citizenship were still inaccessible.”[2] Issues politically made it even more difficult for black citizens to gain a feeling of acceptance and belonging. In 1876, it became more evident that the Republican Party – the Party of Lincoln– no longer viewed African Americans’ civil and political rights as an important component to its platform, as the nation as a whole began to focus on white sectional reconciliation.[3] The state-supported white supremacy was directly mirrored in the deliberate exclusion of black Americans’ participation in the nation’s Exhibition.

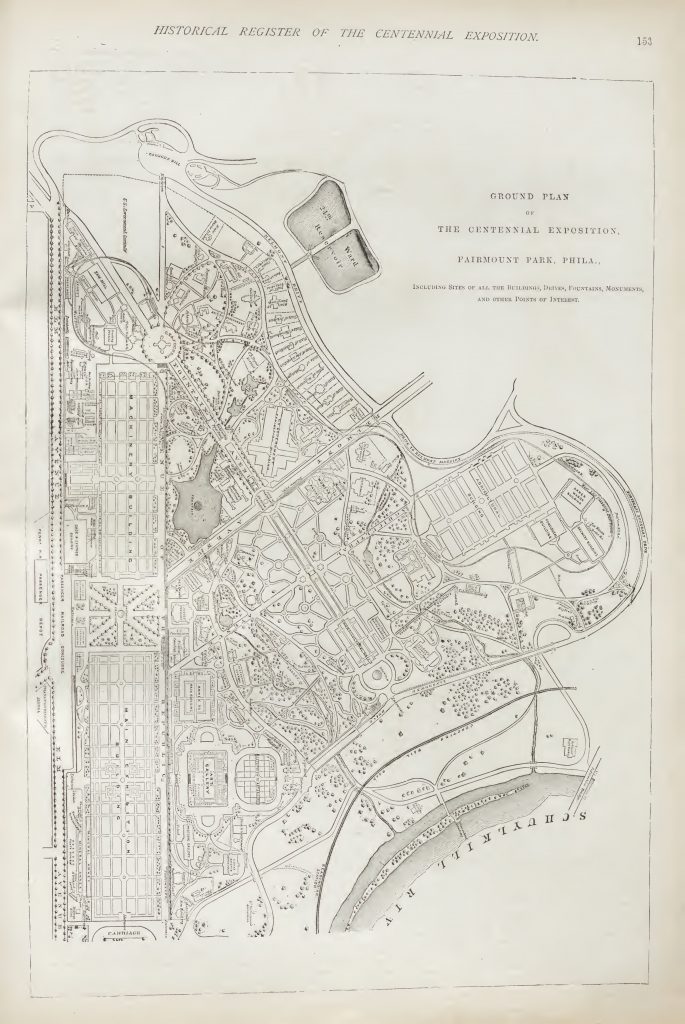

The Centennial Exhibition was expansive, with the total fairgrounds stretching across 450 acres of Fairmount Park.[4] Primary buildings included the main building, the art gallery, and the machinery, agricultural, and horticultural buildings, covering a total of 48.47 acres, with an additional 200–250 smaller special buildings erected to support other nations.[5] With an abundance of pavilions, all of these spaces highlighted and showcased the achievements of the United States and other countries. In contrast, representations of black Americans’ achievements “could be found scattered around various pavilions” with specific exhibits and events where “blacks had been invited to participate.”[6] Compared to the size of the exhibition, the minimal representation of the black community in a country bound with a history of antiblack racism, slavery, and continuous mistreatment comes across as a thoughtless attempt to disregard and forget in order to bask in all of America’s glories.

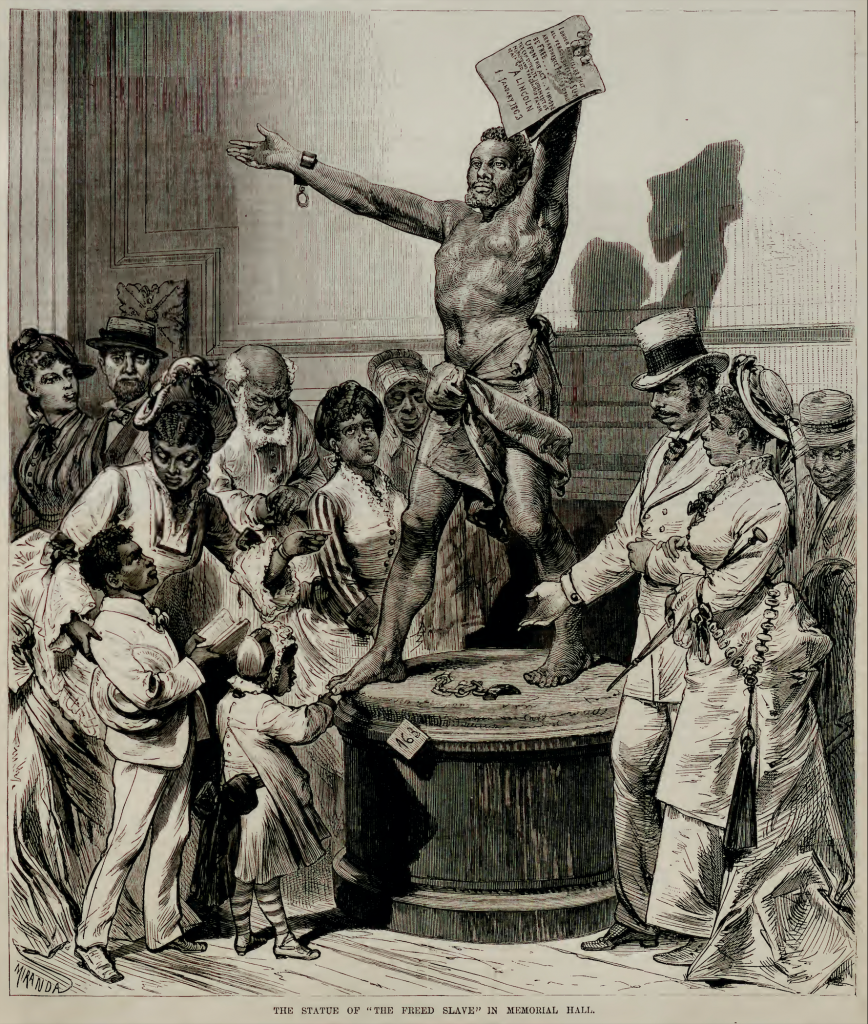

The very few selected pieces that do relate to black representation were curated in a way to show only a select glimpse of history, of course, from the perspective of the white American. Edmonia Lewis was an African American sculptor, and her statue, The Death of Cleopatra, was displayed in the American section of the fine arts exhibit.[7] Edward Bannister’s painting, Under the Oaks, was awarded a medal, “an accolade they almost withdrew once they discovered he was a Negro.”[8] The statue of The Freed Slave was an “ideal presentment of a freedman, made such by the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1st, 1863.”[9] However, this was the work of an Austrian artist and does not accurately reflect the emotions and treatment of black Americans. Frederick Douglas, an abolitionist and orator, was invited to sit on the main platform on the opening day of the Exhibition, however, only after “he was denied entrance to the platform by police who refused to honour his ticket, incredulous that a black man would be welcome in the company of President Grant and the other dignitaries.”[10] In the construction of the 200–250 special buildings, not a single black worker appears to have been employed.[11] “Those few who worked at the Exhibition were relegated to the menial positions of waiters, janitors, and messengers.”[12] The paucity of black representation in the form of exhibits and presence purposely hid certain truths of the nation, but even through hardship and resistance, their minimal appearance allowed for their participation in the public realm.

African American leaders, activists, orators, writers, and the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church envisioned the possibility of the Centennial as an opportunity to transform the white racial perspective. Benjamin Tucker Tanner was the first and most vocal “African Methodists to clamour for official denominational involvement” in the Centennial Exhibition.[13] Tanner proposes that a bronze statue of Richard Allen, the founder of the AME Church, would “tell mightily in the interest…not only for our church, but of our whole race.”[14] However, not only did activists have to overcome merging the past with the future, there was also the struggle of scarce financial resources. “Many African Americans were struggling for educational advancement, economic uplift, and, indeed, their very survival in a holistic racist society,” making it difficult to balance and put emphasis on a single factor in particular.[15] The monument could be used as a link between the past and future generations, providing a visual display for educational purposes. Any attempt to participate in the Centennial Exhibition on behalf of black Americans was halted by the Exposition organizers, further contributing to the burdening superiority of the white Americans. Unsurprisingly, the goal of erecting a permanent monument, just as the other nations were doing, was quickly halted, and instead the organizers “agreed to provide space in Fairmount Park for the Allen statue, but required that it be removed from the grounds within sixty days after the closing of the Exposition.”[16] The original date to unveil the sculpture was July 4th, 1876 (Independence Day), but was then postponed until September 22, in line with the anniversary of Lincoln’s preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in 1862. “During the transport of the monument from Cincinnati to Philadelphia…a railroad accident rendered the entire pedestal irreparably damaged,” but the bust of Allen, “which sat protected in a marble alcove, survived unharmed.”[17] The sculpture was finally unveiled on November 2, 1876, eight days before the closure of the Centennial Exhibition.

The curated portrayal the Exhibition organizers attempted to create of black Americans does not accurately reflect their own perception themselves. Black Americans continuously have been disregarded and misrepresented, forcing them to continually overcome their unjust treatment. The white American perception of the African and African American population in the United States projects ignorance and superiority, which were also reflected in the Centennial Exposition of 1876. The goal was to portray America as a contender in the world, showing its strengths and developments; however, the celebration and excitement relies on a manipulated lie based on the desire to move on from regretful and continual mistakes. The Exhibition gave America yet another opportunity to easily mitigate and dampen their past actions by silencing and controlling those deemed as inferior.

Notes

[1] Wilson, Mabel. “Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums.” Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012. 26.

[2] Ibid., 27.

[3] Kachun, Mitch. “Before the Eyes of all Nations: African-American Identity and Historical Memory at the Centennial Exposition of 1876.” Pennsylvania History 65, no. 3 (1998): 300-323. 314.

[4] Wilson, Mabel, Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums, 26.

[5] Leslie, Frank and Frank H. Norton. “Frank Leslie’s Historical Register of the United States Centennial Exposition, 1876.” Vol. r. 52, item 9. New York: Frank Leslie’s Publishing House, 1877. 36.

[6] Wilson, Mabel, Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums, 28.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Leslie, Frank and Frank H. Norton. “Frank Leslie’s Historical Register of the United States Centennial Exposition, 1876.” 162.

[10] Kachun, Mitch, Before the Eyes of all Nations: African-American Identity and Historical Memory at the Centennial Exposition of 1876, 309.

[11] Foner, Philip S. “Black Participation in the Centennial of 1876.” Phylon 39, no. 4 (1978): 288.

[12] Kachun, Mitch, Before the Eyes of all Nations: African-American Identity and Historical Memory at the Centennial Exposition of 1876, 308.

[13] Ibid., 311.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., 315.

[16] Ibid., 314.

[17] Ibid., 318.

Bibliography

Foner, Philip S. “Black Participation in the Centennial of 1876.” Phylon 39, no. 4 (1978): 283-296.

Kachun, Mitch. “Before the Eyes of all Nations: African-American Identity and Historical Memory at the Centennial Exposition of 1876.” Pennsylvania History 65, no. 3 (1998): 300-323.

Leslie, Frank and Frank H. Norton. “Frank Leslie’s Historical Register of the United States Centennial Exposition, 1876.” Vol. r. 52, item 9. New York: Frank Leslie’s Publishing House, 1877.

Wilson, Mabel. “Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums.” Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012. 1-29.

Images

Cover Image: Leslie, Frank and Frank H. Norton. “Frank Leslie’s Historical Register of the United States Centennial Exposition, 1876.” Vol. r. 52, item 9. New York: Frank Leslie’s Publishing House, 1877. 72-73.

Image 01: Leslie, Frank and Frank H. Norton. “Frank Leslie’s Historical Register of the United States Centennial Exposition, 1876.” Vol. r. 52, item 9. New York: Frank Leslie’s Publishing House, 1877. 153.

Image 02: Leslie, Frank and Frank H. Norton. “Frank Leslie’s Historical Register of the United States Centennial Exposition, 1876.” Vol. r. 52, item 9. New York: Frank Leslie’s Publishing House, 1877. 133.

Image 03: Bethal, Mother, Allen_BUST Black Background, June 22, 2010, Flickr accessed on February 16, 2021 https://www.flickr.com/photos/48946341@N02/4724560383/in/album-72157623990273341/.