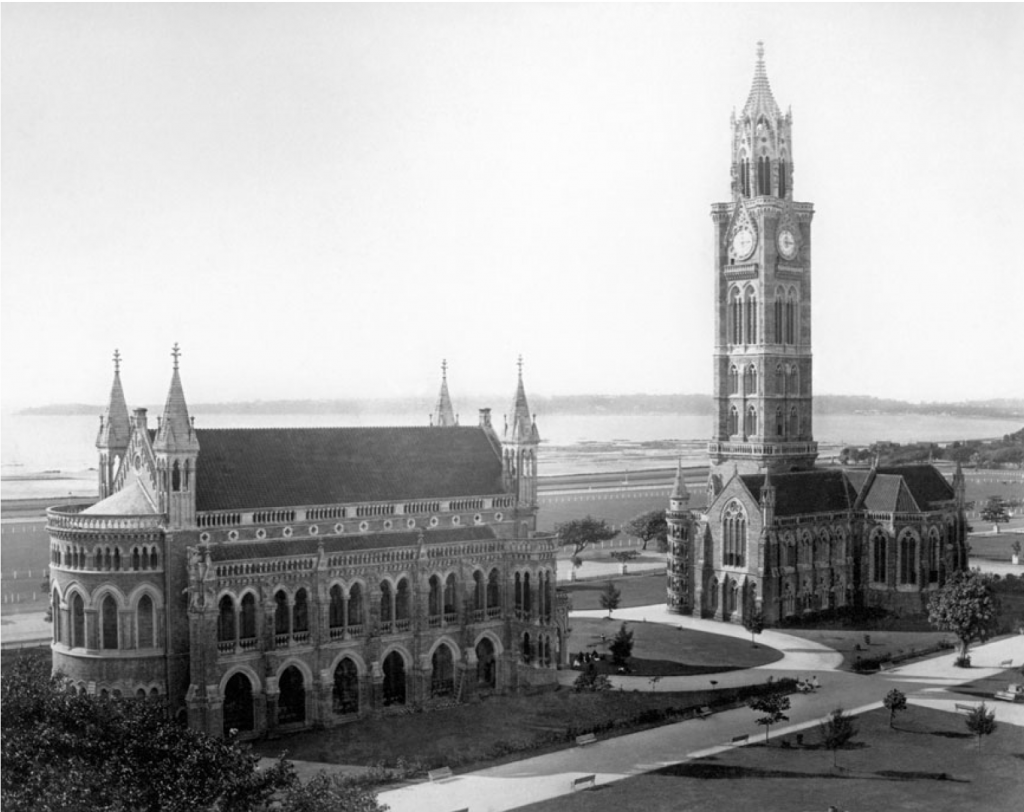

In the late nineteenth century, Bombay transformed from a city of warehouses to become one of Britain’s finest imperial cities. As trade, wealth, and the population flourished, the colonial government embarked on the long-contemplated project of demolishing the old fort walls, to make room for the envisioned metropolis1. As Preeti Chopra discusses in her book, A Joint Enterprise, “the fall of the fort walls opened up the plain, creating a new public arena for government offices and public institutions.”2 The British government began conceptualizing a complex of institutional buildings centred around an oval green, that would eventually give form to the newly established University of Bombay. Over the next two decades, this area would come to be home to several of Bombay’s most prominent Victorian buildings: Government Secretariat (1867-74), the Convocation Hall (1869-74), the High Court (1871-78), the Electric Telegraph Department (1871-74), the Post Office (1869-72), and the University Library and Rajabai Clock Tower (1869-78).

Each of these buildings housed an imperial institution that continued and carried forth the bidding of the crown. As a result, each building in its own way represented a form of power and control of the British Raj in India. The Rajabai Clock tower embodies the clearest symbol of the British Raj, as it serves no purpose other than to be an ever-present symbol within the landscape. The British utilized the clock tower, not to represent the people of the land in which they inhabited, but to provide a monument on the horizon of the Crown’s dominion over them.

A Conspicuous Symbol of the Raj

The Rajabai Clock Tower, 1869-1874, was designed and situated to be the most prominent structure in the city. These ambitions were recognized early by the architect, Sir Gilbert Scott: “I have made it [the tower] very lofty that it may be conspicuous throughout the city.”3 Scott’s design appeared to achieve his intention, as evidenced in the 1876 A Guide to Bombay, which describes the tower, only partially completed at the time, as “already forming such a conspicuous feature in the panorama of Bombay.”4 Upon completion, the tower soared to a height of 280-feet, approximately twenty-eight stories, achieving the status of the tallest structure in Bombay, which it would retain for several decades.

Towers and Clocks in Provincial India

Such towers were becoming increasingly present in the urban landscape of provincial Britain. In An Imperial Vision, Thomas Metcalf remarks on the phenomenon of the sudden increase of clock towers throughout India, and the significance of the tower’s symbology within its post-mutiny context. Following the devastation of the 1857 Indian Rebellion, the British Raj strived to cement their colonial presence in India through the extension infrastructure. Notably, many of the first upgrades were clock towers, set down in urban centers of the squashed 1857 revolt.5 Metcalf theorizes that the British understood and utilized the tower typology as symbol of conquest, as this tactic and symbology was known to the Indian public. “Following the precedent of Qutb Minar, set up by the first Muslim conquerors of Delhi about 1200 AD, they [the towers] told of conquest, not the hours.”6

For over five-hundred years, towers rose above centers in India, signifying and representing the controlling regime. In 1875 British construction publication, The Builder, wrote of the completion of a clock tower in Delhi’s oldest market, Chandni Chowk, “the Municipal Commissioners of Delhi have affected many improvements in that city since the mutinies … the latest improvement is the new clock-tower, which stands in the centre of the Chandni Chowk, opposite the town-hall, representing the crown”.7 Metcalf concludes, that it is difficult to see this clock tower, and subsequent towers constructed by the British across India in this time period, “as anything other than modern day Qtub Minars.”8 Coincidentally, Bombay’s Rajabai clock tower was completed in the same year as Delhi’s Chandni Chowk tower, 1874. It is to theorize that the motivations with which the Chandni Chowk tower was constructed; conquest, control and power, also influenced the building of the Rajabai clock tower.

Figure 2.2. Delhi Clock Tower, 1874, constructed in the Chandni Chowk, Delhi’s oldest market and an important centre of the 1857 Indian rebellion. The British government constructed the tower in response to the mutiny.

The clock tower was a particularly effective method of authoritative control, as it not only provided a looming visual landmark within the landscape, it also created an audible reminder of power and control. Clocks themselves represented “a new era” and technological progress: these developments in clock technology were wielded by the British in an effort to create an increasingly efficient society and productive workforce. The methods of utilizing the clock as a tool of control were pervasive throughout Imperial Britain. In the book Work Ethic in Industrial American, author Daniel T. Rogers writes on how the clock and its corresponding tower was utilized as a tool of control in British controlled mill towns in America:

“Even the architecture of the mill districts reflected it. In scores of nineteenth – and early twentieth-century mill towns, no feature stood out more prominently than the great, looming bell towers … Where clocks and watches remained rare, the factory bells served the essential, utilitarian function of ringing the labor force out of bed, into work and home again at the day’s end.”9

The British continued these tactics to the Imperial reaches of India. Metcalf writes, “the British had always railed against the laziness and lethargy of their Indian subjects. With its hourly chiming gongs, the clock helped to remind the students and passersby not only of the supremacy of the Raj but the virtues of punctuality.”10 With this, the Raj sought to influence every action, wielding their control into the daily life of its subjects.

Along with the quarter hour chimes, the Rajabai clock tower symbolized the presence and dominion of the British Raj in a further, extremely literal way. The clock tower was equipped with “a peal of joy bells” that could play sixteen melodies including; Home Sweet Home, God Save the Queen and Rule Britannia.11 These tunes are unmistakable as imperial and cannot be argued to represent the people native to India. The erroneous presence of these songs within the Indian context is clarified at a much later date: with the eventual Indian Independence from Britain in 1947, the clock immediately ceased to chime these imperial anthems.

The Gothic Style as a British Device

The Rajabai clock tower is of neo-gothic design which typifies Bombay’s loyalty to the gothic revival tradition and its resistance to the Indo-Saracenic trend of architecture that was dominating public buildings elsewhere in India. The resistance to the popular Indo-Saracenic, an “indian inspired” architectural style, could be explained by the way Bombay conceived of itself: “facing towards Europe on the west coast of India … Bombay sought to define itself to some degree as a European city.”12 The gothic style owed its reasurgance to Britain and had come to be considered a quintessential archetype of Britain. In An Imperial Vision, Metcalf even stipulates that “in the view of such architects as Gilbert Scott”, the architect of the Rajabai clock tower, “gothic was considered a national style, whose use would permit Britons to celebrate the achievements of our country.”13 As Bombay’s tallest structure, the Rajabai tower with its neo-gothic architecture, did not seek to represent the traditions of the country in which it was in, but rather to give homage to the national appearance of Britain.

The Rajabai clock tower further demonstrates the stubborn allegiance to European architectural traditions through its half-hearted attempt to accommodate the Indian climate. Chief architect Sir Gilbert Scott, modeled the tower after Giotto’s Campanile in Florence and was said to follow the Venetian gothic style.14 At the time, the venetian gothic style with its open arcading and polychromatic texture, “appealed to observers as the most ‘Oriental’ of gothic styles, and hence the ‘best adapted for the climate of Bombay.’”15 To conclude that Italian architecture would be logically suited for Bombay because they both had warm climates, exemplifies the extremely Eurocentric position of the British. However, this could have been expected, as Sir Gilbert Scott never visited India himself and from his poorly-informed position in London, this oversimplification would seem logical.

The use of the venetion gothic style and the modeling after Giotto’s campanile gives rise to another issue: the correlation of the gothic form with religious sentiment. At the same time the Rajabai tower was conceived, a debate was raging on the appropropriate style for christian churches within India. The Indo-Saracenic style, which adopted architectural elements from regional Indian styles, was thought to be inappropriate for churches as the appropriated elements came from Islamic and Hindu origins. It was determined that the “gothic style expressed religious devotion” and that the church “must be in keeping with a style in which all our feelings of devotion are associated.”16 The paradox is: although the Indo-Saracenic style was determined to be inappropriate for christian buildings, the gothic style was deemed as well-suited for secular buildings. Regardless of this determination by British authorities, the gothic style nonetheless exuded christian sentiment. The Rajabai clock tower illustrates this contradiction. When designing the tower, Scott stated his intentions; “I have endeavored to give the Tower a look differing, so far as may be, from that of a church tower.”17 However, many architectural historians have critiqued the result as far from successful as the tower overwhelmingly conveys an ecclesiastical air. Scott’s failure is doubled when considering the patron of the tower. The required finds were donated by a single benefactor, Premchund Roychund, who was a pious Jain.18 It is curious to wonder, as Roychund stood in the shadow of the tower in which he supplied, if he felt truly represented or only saw the reflection of the British Raj’s own religious motivations.

Ornamentation as Superficial Representation

Although the overarching form of the Rajabai tower is definitively gothic of European inspiration, the ornamentation of the building incorporated unique elements that paid homage to its Indian context. Ornate, serpentine carvings of local flora and fauna outline the windows. Most famous are the impressive, eight-foot-tall sculpted figures surrounding the octagonal corona. A collection of twenty-four figures adorn the tower and finials, each figure representing a different caste of western India. It could be presumed that Indians could have felt represented or even honoured to see a depiction of the public adorning such a powerful and notable symbol of the city.19 Inversely, the representations of the different castes may have felt disconnected from their own reality. Preeti Chopra challenges the inclusion of the figures “as an illustration of the British obsession with documenting and characterizing India’s tribes and castes and their concern with types”.20 Chopra’s criticism is further supported, when considered the fact that the sculptures are done in a highly European fashion and do not stylistically resemble carvings native to the region. This signifies that the execution of the sculptures were “most likely based on instructions from the British, as a display of the colonial regime’s interest.”21 Any doubt surrounding the true motivations of the British can be expelled when extending the consideration to the interior decoration. Upon entering the tower portico, the ornamentation shifts to be entirely British in origin, with the capitals of the interior columns adorned with the busts of Shakespeare, Holmes and British kings and queens of past.

Notes

1 Chopra, Preeti. A Joint Enterprise: Indian Elites and the Making of British Bombay. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 1.

2 Chopra, A Joint Enterprise, 22.

3 Garware, Anita. “Timeless Heritage.” The Indian Heritage Society, Mumbai, 2015, 14.

4 Maclean, James Mackenzie. A Guide to Bombay: Historical, Statistical and Descriptive. (Bombay: The Bombay Gazette, 1876), 173.

5 Metcalf, Thomas R. An Imperial Vision: Indian Architecture and Britain’s Raj. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 55.

6 Metcalf, An Imperial Vision, 55.

7 The Builder XXXIV (February 14, 1874), 133.

8 Metcalf, An Imperial Vision, 55.

9 Rodgers, Daniel T. The Work Ethic in Industrial America, 1850-1920. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), 154.

10 Metcalf, Thomas R. “Architecture and the Representation of Empire: India, 1860-1910.” Representations 6, no. 1 (April 1984): 56.

11 Maclean, A Guide to Bombay, 173.

12 Metcalf, An Imperial Vision, 96.

13 Metcalf, An Imperial Vision, 3.

14 Metcalf, An Imperial Vision, 92-93.

15 Metcalf, An Imperial Vision, 94.

16 Metcalf, An Imperial Vision, 58.

17 Garware, “Timeless Heritage,” 13.

18 Wacha, D.E. “Premchund Roychund: His Early Life and Career.” The Times Press. 1913.

19 Chopra, A Joint Enterprise, 69

20 Chopra, A Joint Enterprise, 67.

21 Chopra, Preeti. “The City and Its Fragments: Colonial Bombay, 1854-1918.” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2003), 435.

Bibliography

Chopra, Preeti. A Joint Enterprise: Indian Elites and the Making of British Bombay. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

Chopra, Preeti. “The City and Its Fragments: Colonial Bombay, 1854-1918.” PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2003.

Garware, Anita. “Timeless Heritage.” The Indian Heritage Society, Mumbai, 2015.

Maclean, James Mackenzie. A Guide to Bombay: Historical, Statistical and Descriptive. Bombay: The Bombay Gazette, 1876.

Metcalf, Thomas R. An Imperial Vision: Indian Architecture and Britain’s Raj. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

Metcalf, Thomas R. “Architecture and the Representation of Empire: India, 1860-1910.” Representations 6, no. 1 (April 1984): 37–65. https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.1984.6.1.99p0045t.

Rodgers, Daniel T. The Work Ethic in Industrial America, 1850-1920. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

The Builder XXXIV (February 14, 1874).

Wacha, D.E. “Premchund Roychund: His Early Life and Career.” The Times Press. 1913.

Figures

Figure 1. Chopra, Preeti. A Joint Enterprise: Indian Elites and the Making of British Bombay. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011, 67.

Figure 2.1. Anonymous. Qutb Minar En Alai Darwaza in Delhi. 1880 1865. Photograph, 296mm x 209mm. RP-F-F02487. Rijks Musuem.

Figure 2.2. The Builder XXXIV. Delhi Clock Tower, February 14, 1874, 133.

Figure 2.3. Bourne & Shepherd. Raadsgebouw van de Universiteit Te Bombay in India. 1875. Photograph. Universiteit Leiden.

Figure 3. Burke, Eric Keast. Looking down on the City of Bombay, towards the South East, from the Summit of Rajabai Tower. December 11, 1919. Photograph. Australian War Memorial.

Figure 4. Chopra, Preeti. A Joint Enterprise: Indian Elites and the Making of British Bombay. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011, 68.