Forming a portion of the St. Lawrence Market façade in Toronto, its first official city hall is part of a legacy of facadism in Toronto architecture, where buildings are preserved to meet the goal of heritage conservation of facades. As we seek a decolonized society, it is important to question the role our preserved architecture played in settler colonialism.

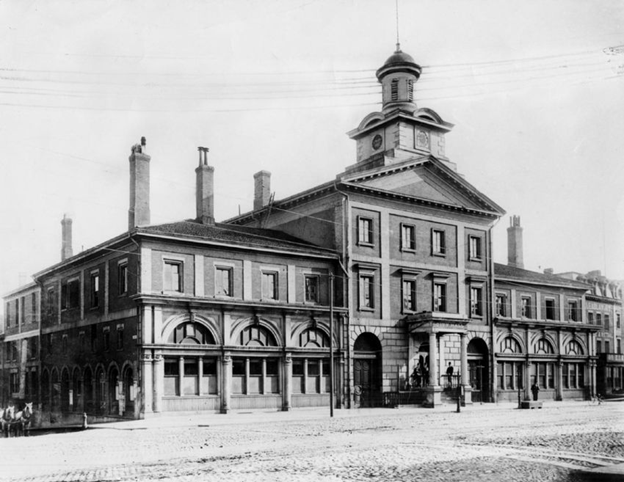

In 1845, Toronto built it is first official city hall after the passing of the municipal act and Upper Canada’s declaration of York which established the City of Toronto.1 The (old) Old City Hall, known as the ‘new market house’, served as Toronto’s city hall until 1899.2 Motivated by self-interest and civic pride, the city hall building was to be a monumental agora building, which set Toronto up to become a city of importance for commerce in British America.3 Designed in the Georgian, Palladian style 4, the façade was composed of red brick and white stone.5 This building was of particular importance for the architectural future of the city, because prior to its construction Toronto star, writer Peter Otto suggested, “there is no city that needs a little architectural taste more than ours.” 6 This building arose within the larger context of colonization which had changed from a settlement in support military trading posts, towards commercial growth, permanent occupation, and growing independence from British Colonial rule. While the building itself is not an explicit form of dispossession or erasure, it contributed to the larger system of settler colonialism due to its Eurocentric orientation and loyalty, design of

authority and control and development of a capitalist economy.

The establishment of Toronto as a municipality and the resulting development of a city hall allowed the city to gain more independence from British colonialism. However, it shifted the city towards larger settler colonialism, by formalizing permanent settlement based upon Eurocentric views of society and control. The decision of the location of the city hall development of the city hall, and its citizenship, were the result of British rule. Toronto, (formally York), located on Lake Ontario was

established as a military trading port, to support colonialism.7 The growing population were encouraged to settle in this region, to supply and support this military operation, and the new capital of Upper Canada (now Ontario). The location of the market and town hall itself were dictated by the Upper Canada Act.8 The incorporation of the city, set a precedent that Toronto’s history did not begin until incorporation, ignoring the indigenous displacement or complicated land-treaty, which continues to this day.9 Further the architect, Henry Bowyer Lane, was educated and trained in England.10 The building’s form reflects this influence. The symmetry and proportion, minimal detailing, restrained ornamentation

, and use of local brick in the Palladian Georgian style are reflective of loyalty to Eurocentric ideals. Georgian-style architecture was popular with British Loyalists because they felt it projected their loyalty to Britain.11 This Eurocentric view perpetuates the colonialist agenda of a ruling European class in British North America, supporting the larger settler colonialist system.

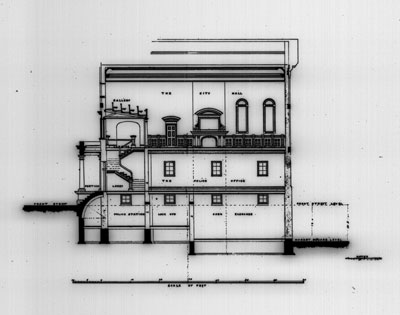

Beyond the general Georgian style of the building, the functions, and details project authority for the Anglo-Saxon ruling class. The building had a 3-storey center block flanked by symmetrical 2-storey wings. Off the main promenade was the entry to the council spaces through two Tuscan columns with an entablature and pediment. The council chambers, public hall, and mayor’s office occupied the second and third floors of the 3-storey center block.12 Flanking the pediment were 2 archways that led to the public market.13 The wings featured a neoclassical colonnade façade which were occupied by a police station and merchant shops.14 Each of these elements helped in developing a sense of authority.

CITY HALL, 1849? (JH)

Toronto Public Library (TRL), Howard Drawing 411.

A combined police station, public market, public hall, and town hall, suggests a need for control and surveillance of the public realm. Public markets were considered ‘naturally public’, therefore, the addition of the town hall to markets was popular in European cities to assert control over the public realm.15 The addition of the public hall furthered this sense of control, as public halls were considered arbiters of community standards in the British tradition16, allowing for influence through both legal and social means. Locating the city offices on the second and third floors added additional surveillance of the public market from above. Beyond the location of functions, the idea of authority is further articulated by the building façade. Both neoclassical Tuscan columns and colonnades were architectural tools often employed in government buildings to project stability and power. These have also been utilized on this building’s façade. The city comprised primarily of Anglo-Saxons 17 seeking authority and control contributes to the settler colonialist system by furthering their sense of control and dominance of land to the exclusion of others.

Like many other colonialist infrastructures, the city hall was closely tied to capitalism. The town hall was considered part of a group of monumental town halls which were popular at the time. Monumental town halls were, “physical embodiments of communities commitment to economic and social progress” 18. A monumental town hall was a form of ‘boosterism’, which promoted towns as stable and prosperous which made them good places to do business 19. This capitalist agenda is reflected in the prominence of the stores and the market in the building design. The inclusion of a public market indicates the importance of business in the civic life of the city. Having grand archways to enter the market towards the center of the building adds importance to this use. Having stores which open onto the main promenade prove commerce was integral to the building design. Furthermore, the spaces were designed by and for business and political elite which were Anglo-Saxon men.20 Lane was thought to receive the building commission due to his family relationship with Willian Henry Boulton who sat on the city council.21 Boulton and Lane were both educated in England.22

Though the indicators are not explicit at first examination, when viewing the original Toronto city hall through the lens of settler colonialism, the building clearly contributed to capitalism, Anglo-Saxon authority over land and the Eurocentric vision of society. This need not eliminate it from historical preservation but may help explain the elements which remain in its new form as the St. Lawrence market. The goal of a public market on this land has persisted despite changes to the other uses. It no longer serves as a police station, public hall or town hall which reduced the surveillance and authority experienced in the remaining market. The neoclassical elements and columns along with the pediment have been removed, leaving the only reference the brick which became a key feature of local architecture. Long before permanent settlement, this was a place of trading which was inclusive for the indigenous, by remaining a market over the centuries this may ultimately serve a decolonized future. Though it is noteworthy that the beauty of a wigwams that were the original architecture of this land is no where to be seen.

photograph. The Toronto Convention and Visitors Association https://www.seetorontonow.com/attractions/in-the-spotlight-st-lawrence-market-complex/

1 Otto, | By Stephen. “The Creation of Toronto’s First City Hall and Market Buildings,” March 3, 2016. http://spacing.ca/toronto/2016/03/04/the-creation-of-torontos-first-city-hall-and-market-buildings/.

2 Ibid. Otto

3 Ibid. Otto

4 City of Toronto. “Institutional Toronto.” City of Toronto, December 11, 2017. https://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/history-art-culture/museums/virtual-exhibits/textures-of-a-lost-toronto/institutional-toronto/.

5 “St. Lawrence Market : History.” Saint Lawrence Market. Accessed February 18, 2021. http://www.stlawrencemarket.com/history.

6 Ibid Otto

7 Delaney, Lesley Jill. “Spaces of appearance: The civic square in the design of new Canadian city halls.”

(1998): 3753-3753. pg.84

8 Delaney pg. 91

9 Freeman, Victoria ““Toronto Has No History!”: Indigeneity, Settler Colonialism, and Historical Memory in Canada’s Largest City”. Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine 38, no. 2 (2010) : 21–35.

https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.7202/039672ar pg 331

10 Dictionary of Canadian Biography. “Biography – LANE, HENRY BOWYER JOSEPH – Volume X (1871-1880) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography.” Home – Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Accessed February 18, 2021.

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lane_henry_bowyer_joseph_8E.html.

11 Ontario Architecture. “Building Styles.” Georgian. Accessed February 18, 2021. http://www.ontarioarchitecture.com/georgian.htm.

12 Ibid. St. Lawrence market

13 Ibid. St. Lawrence market

14 Ibid. St. lawrenece market

15 Tittler, Robert, pg 12. Architecture and Power. The Town Hall and The English Urban Community c. 1500-1640 Oxford Claredon, 1991

16 Delaney pg. 98

17 Delaney pg. 110

18 Delaney pg. 98

19 Delaney pg. 67

20 Delaney pg. 110

21 Ibid. Dictionary of Canadian Biography

22 Ibid. Dictionary of Canadian Biography

Bibliography:

City of Toronto. “Institutional Toronto.” City of Toronto, December 11, 2017. https://www.toronto.ca/explore-enjoy/history-art-culture/museums/virtual-exhibits/textures-of-a-lost-toronto/institutional-toronto/.

Delaney, Lesley Jill. “Spaces of appearance: The civic square in the design of new Canadian city halls.”

Dictionary of Canadian Biography. “Biography – LANE, HENRY BOWYER JOSEPH – Volume X (1871-1880) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography.” Home – Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Accessed February 18, 2021.

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lane_henry_bowyer_joseph_8E.html.

Freeman, Victoria ““Toronto Has No History!”: Indigeneity, Settler Colonialism, and Historical Memory in Canada’s Largest City”. Urban History Review / Revue d’histoire urbaine 38, no. 2 (2010) : 21–35.

https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.7202/039672ar pg 331

Ontario Architecture. “Building Styles.” Georgian. Accessed February 18, 2021. http://www.ontarioarchitecture.com/georgian.htm.

Otto, | By Stephen. “The Creation of Toronto’s First City Hall and Market Buildings,” March 3, 2016. http://spacing.ca/toronto/2016/03/04/the-creation-of-torontos-first-city-hall-and-market-buildings/.

“St. Lawrence Market : History.” Saint Lawrence Market. Accessed February 18, 2021. http://www.stlawrencemarket.com/history.

Tittler, Robert, pg 12. Architecture and Power. The Town Hall and The English Urban Community c. 1500-1640 Oxford Claredon, 1991