A Conflict of Dominion at the Slave Quarters

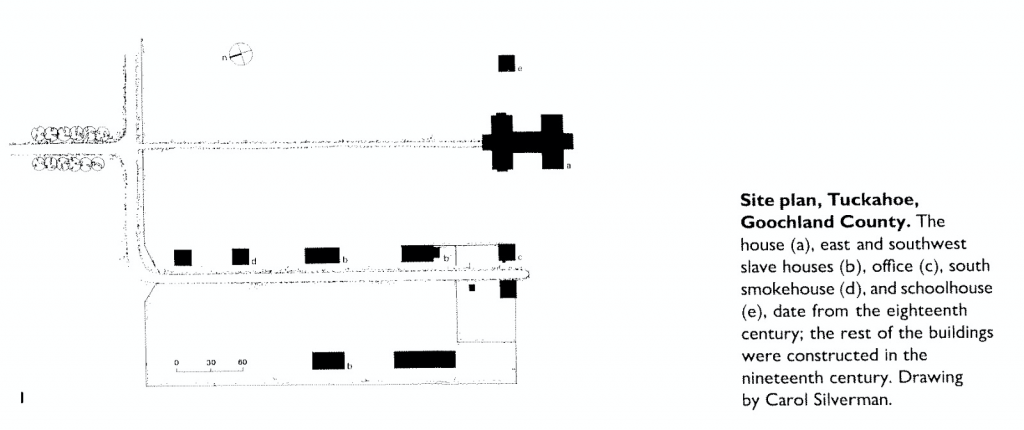

Tuckahoe slave labour camp is located ten miles west of Richmond, Virginia and was first settled by the Randolph family in 1714 and was at one point the childhood home of Thomas Jefferson.1 Construction of the main house began soon after and ultimately underwent the addition of a number of outbuildings including an office, smokehouse, schoolhouse and four slave houses. Tuckahoe exists as part of a larger system of plantation slavery, an instrument of British colonial expansion that once dominated the American South. Such a system relied greatly on the exploited labour of enslaved Africans, who’s necessary role within the plantation system creates a contested presence within its spacial landscape, which the slave holder thus attempts to control and dominate. Tuckahoe presents clear and intentional spacial manifestations of such control and dominance through means of architectural symbolism, scale and placement.

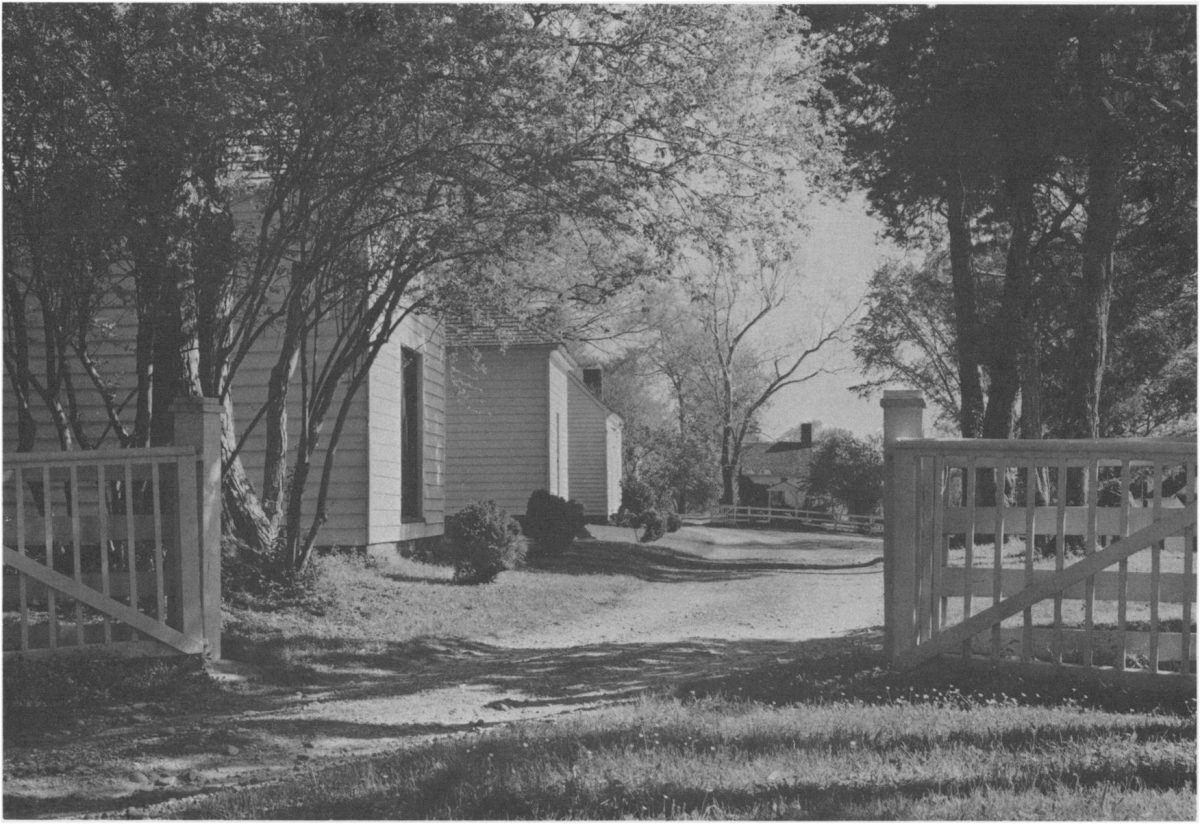

The designated slave quarters exist within the plantation landscape as “instruments of social control.”2 Prior to the eighteenth century, designated slave quarters were fairly uncommon. Those enslaved were either stationed in the slaveholder’s house or occupied lofts in certain service buildings.3 Only toward the end of the 17th century, did a pattern of division and segregation begin to emerge and become more strictly enforced through spacial and architectural means.4 From the perspective of the slave holder, the slave quarters were part of the “working landscape”5, which, to an extent, informed their location within the site. Ideally the quarters were hidden from view of the main house. Tuckahoe, however, presents an arrangement that was less conventional in the eighteenth century, where the slave quarters, along with other administrative buildings, such as the office and smokehouse, sit along a street adjacent to the road leading to the main house, aptly named, Plantation Street. This placement is considered to have been a deliberate tactic to impress those approaching the house with a display of slave ownership, in an attempt to “enhance the visitor’s perception of the planter and his estate”.6 The slave quarters came to represent a symbol of immense wealth, of which could only be acquired through the exploitation of the enslaved labourers, of course. Proximity to the main house may also allow for a level of surveillance over the cabins, further establishing a symbolic dominance. This linear layout, later became precedent to most nineteenth century slave labour camps.7

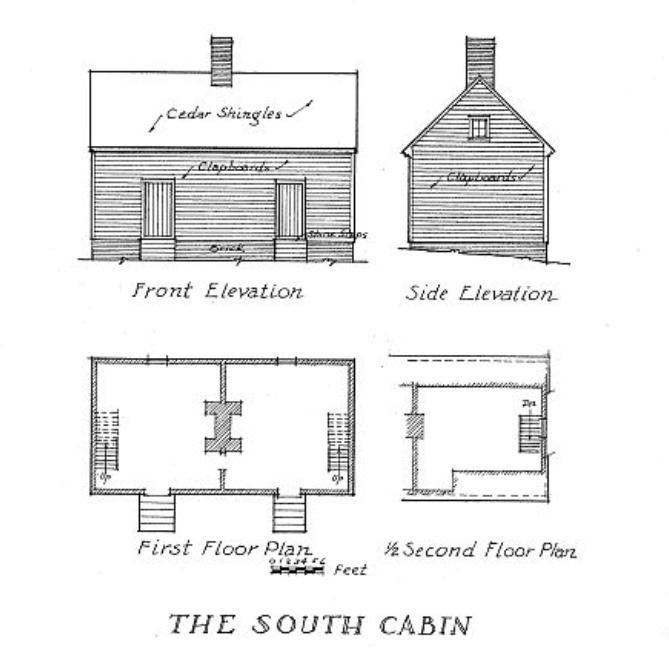

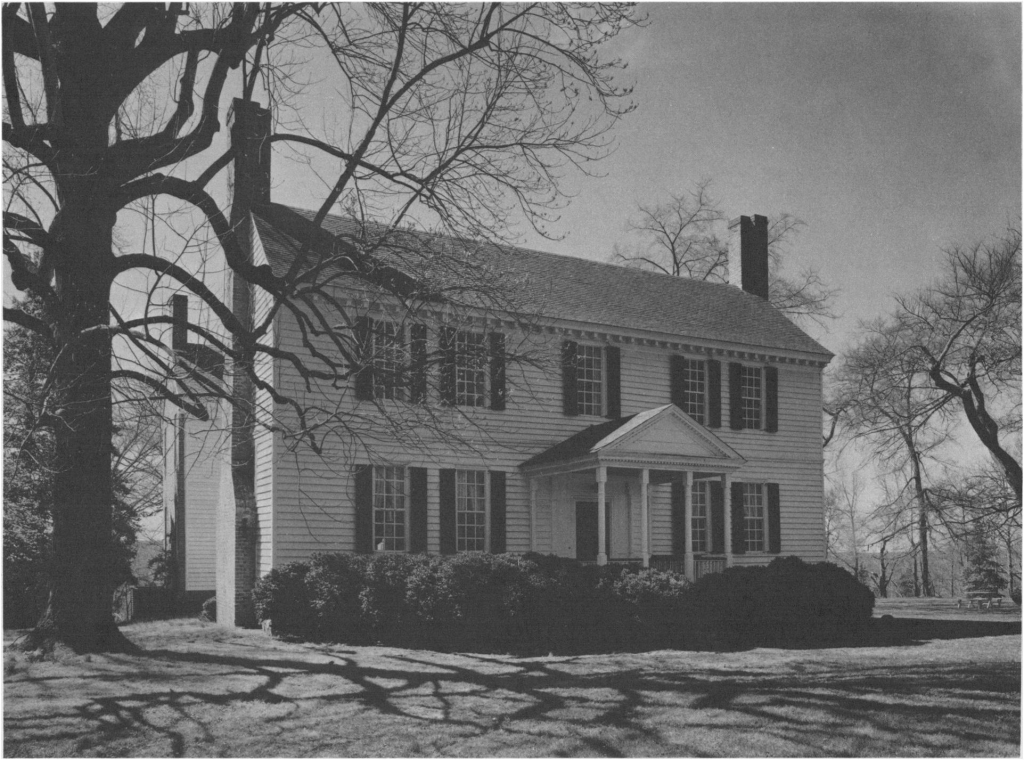

This symbolic association with wealth is in inherent contradiction with the humble, “almost inconsequential”8 architecture of the cabins themselves. Most slave quarters in Virginia were often of simple log construction with virtually no ornamentation9 and an apparent lack of built in furniture and storage space that was a likely feature of any typical slave’s quarters.10 Such was the case of Tuckahoe’s four slave quarters. Each is a simple one-story frame log structure split into two units from the central chimney in a “saddlebag” configuration11, which was typically done if the space was larger than sixteen by twenty feet.12 Each unit was has access to an exterior door, an interior opening that connects the two, ladder stairs that lead to a sleeping loft above, and was typically shared by between six to twenty four enslaved people at a time.13 The exterior treatment of the cabins mimics the surrounding outbuildings, where the quality of finish is dependant on its visibility from the main house.

The quarters were intentionally designed to look “fittingly primitive”14 to whites, in an attempt to reaffirm racial hierarchy. According to Upton, slave quarters were situated within two “intersecting landscapes”, that of the white slaveholder centred around the main house, and that of the black enslaved labourers, centred around the quarters.15 The white landscape was “both an articulated and processional one”,16 where networks of spaces were intentionally positioned and designed along with the movement through them, in relation to the main house. The enslaved simultaneously operated in another, “private landscape”17 created within and around the cabin walls, where they could exercise some agency. Such includes the installation of fixed and movable shelves, 3 – 5 ft holes in the floor that served as cubby holes or root cellars, and the appropriation, purchase or making of objects as needed.18 Vlach even suggests the minimal nature of the provided dwellings may have inadvertently allowed the enslaved to retain their African identities through the objects they add.19 Outside cabin walls existed space for socializing and space for tending and growing food either to supplement their diet or to barter and exchange among others enslaved.20

The spacial manifestation of dominance is evident within the carefully planned illustrations of the site of the Tuckahoe slave labour camp. The vast, symmetrical main house looms over the rest of the landscape, while other amenities including the slave quarters are ordered along its perimeter. There is account of enslaved people at Tuckahoe referring to the main house as “the great house” with reference to both scale and authority.21 The racial segregation established by the designation of separate slave quarters, however, might not have resonated in the way desired by the slaveholder. For such division facilitated a growing private landscape for those enslaved that wasn’t accounted for within the articulated landscape. In a sense, the segregation of the enslaved to the slave quarters facilitated acts of placemaking and agency over a space, through which communities of their own were formed.

Notes

- Jessie T. Krusen. “Tuckahoe Plantation.” Winterthur Portfolio 11 (1976): 105.

- John M. Vlach, Back of the big house: the architecture of plantation slavery. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 189.

- Ibid, 178.

- Gwendolyn Wright. “The Big House and the Slave Quarters” in Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America, (New York : Pantheon Books, 1981), chap. 3.

- Dell Upton. “White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia.” Places 2, no. 2 (1984): 63.

- John M. Vlach, Back of the big house: the architecture of plantation slavery. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 21.

- Ibid, 78.

- Ibid, 162.

- Gwendolyn Wright. “The Big House and the Slave Quarters” in Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America, (New York : Pantheon Books, 1981), chap. 3.

- Dell Upton. “White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia.” Places 2, no. 2 (1984): 61.

- John M. Vlach, Back of the big house: the architecture of plantation slavery. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 22.

- Dell Upton. “White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia.” Places 2, no. 2 (1984): 60.

- Ibid.

- Gwendolyn Wright. “The Big House and the Slave Quarters” in Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America, (New York : Pantheon Books, 1981), chap. 3.

- Dell Upton. “White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia.” Places 2, no. 2 (1984): 63.

- Ibid, 66.

- Ibid, 70.

- Ibid, 61.

- John M. Vlach, Back of the big house: the architecture of plantation slavery. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 165.

- Dell Upton. “White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia.” Places 2, no. 2 (1984): 63.

- John M. Vlach, Back of the big house: the architecture of plantation slavery. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 229.

Bibligraphy

Krusen, Jessie T. “Tuckahoe Plantation.” Winterthur Portfolio 11 (1976): 103-22. JSTOR.

Upton, Dell. “White and Black Landscapes in Eighteenth-Century Virginia.” Places 2, no. 2 (1984): 59-72. eScholarship.

Vlach, John M. Back of the big house: the architecture of plantation slavery. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993. HathiTrust.

Wright, Gwendolyn. “The Big House and the Slave Quarters” Chapter 3 in Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America, New York : Pantheon Books, 1981. Google Books.