A bitter-sweet investigation into the rich history & role that Rogers Sugar played in Vancouver’s development.

The BC Sugar Refinery is a highly industrial building located just behind the railway tracks at the Port of Vancouver, and an easy building to quickly dismiss without giving it a second thought. A series of warehouse buildings and operational spaces are tucked behind the front facade, rendering it nearly invisible from the street. Appearing isolated and seemingly deserted, the refinery carries an immense amount of history that the buildings do not begin to convey.

The sugar industry in Vancouver played an essential role in advancing the development of Western-Pacific Canada and ultimately shaping Vancouver into what we see today. Using a mix of raw cane imports from The Philippines, Fiji, Java and Australia, the BC Sugar Refinery became the first major industry in the Vancouver Metropolitan that was not linked to the area’s natural resources. Its development was accelerated thanks to its coastal proximity and ability to access the Canadian Pacific Railway. The history also carries xenophobic bias, and is deeply embedded alongside the Indian “coolies” field labour production in Fiji. The rich history and wealth of B.T. Rogers would never have been possible if not for the raw sugar imports, where low-paid workers were bonded to the architecture of cane processing, as interchangeable parts that valued high profits above fair labour.

A Brief History

Benjamin Tingley Rogers (B.T. Rogers) later known as the “Sugar King”, established the B.C. Sugar Refinery at just 24 years of age. Rogers, an American that learned the business from his father in both Philadelphia and New Orleans, was working in Montreal at another sugar refinery when he saw the potential for developing a west coast sugar refinery. There were two major factors that favoured Vancouver’s sugar refining economic potential: its coastal proximity for raw sugar imports, and the recent completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The railway was an essential component for the refinery. Rogers discovered that the Montreal refinery was delivering refined sugar by rail to Vancouver, protected by tariffs that restricted the import of San Francisco sugars into the British Columbia market. By opening a refinery in Vancouver, the refinery would have the same tariff protection while eliminating freight transportation costs from Montreal.1

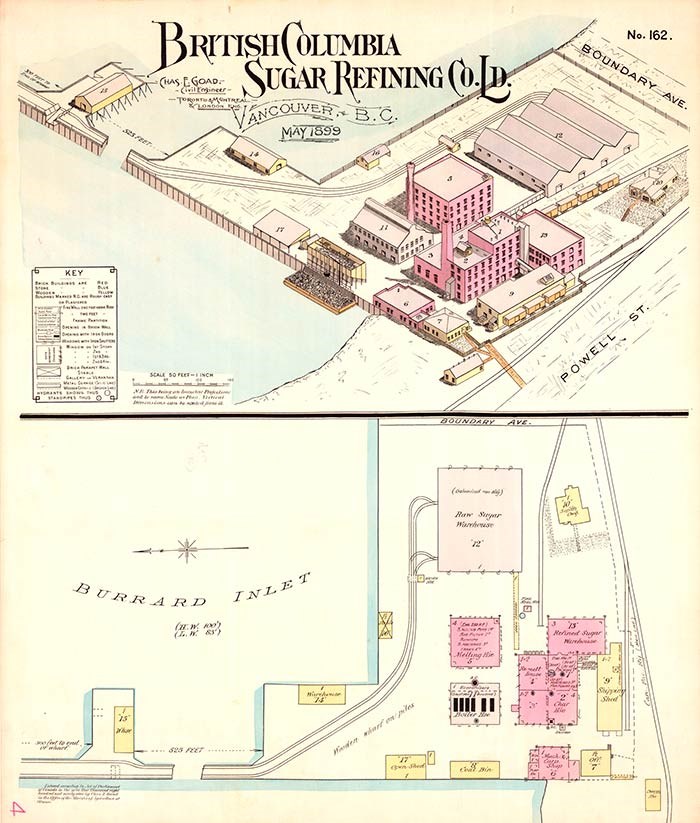

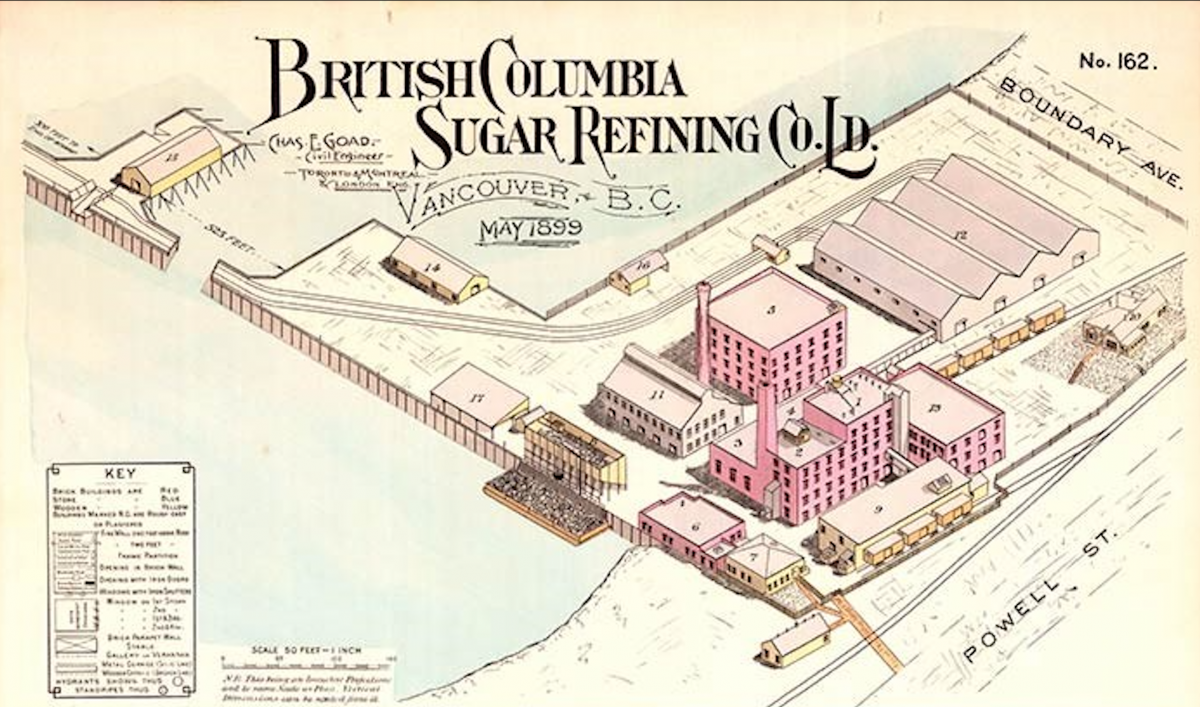

Rogers gained financial support from the president of the Canadian Pacific Railway, William C. Van Horne, and arrived in Vancouver in 1890 to propose the business plan to the City of Vancouver. Given that the city of Vancouver had only been incorporated for four years, they were eager for the proposal to move forward. The city agreed to the majority of Rogers business proposal, donating $30,000 of land in the Burrard Inlet for the refinery. The City Council, however, added a condition to the agreement insisting that the sugar company “shall not at any time employ Chinese labour”.2 This clause was rooted in the city’s tempestuous relationship between Vancouver’s growing Asian immigrant population and an uneasy white population. The city’s xenophobic bias against “Orientals” had been deeply entrenched by the 1886 anti-Chinese riots.3 Rogers accepted all of the amendments suggested by the city council. By 1891, the refinery was producing sugar.4

Despite the company’s policy against migrant workers at the refinery, wages were still substantially lower than the national average and the pay at other sugar refineries in the United States and Canada.5

The Architecture

The buildings making up the BC Sugar Refinery were believed to have been designed by Rogers himself. They have been a controversial topic amongst Vancouver locals. In 1975, The Vancouver Sun newspaper called it the worst building in Vancouver because of the “sheer force of its industrial revolution ugliness”.6 For passengers on the trans-continental train, however, the refinery became a welcomed sight as it represented the journey’s end. Construction of the refinery began in 1891, and was ready to operate in less than six months.7 The refinery site and waterfront property were completed in stages. None of the original refinery buildings have survived, but there are smaller buildings still visible on the site including the first “melt house” where molasses is extracted from raw sugar, which now houses a cafeteria. The brick warehouse building was also built in stages beginning in 1903. The building curves along the railway tracks, with south facing windows. A lack of north-facing windows causes the space to get very warm in the summer months.8

Raw Sugar Import

A sugar refinery begins the refining process using raw sugar that is extracted from mills at the cane plantations. Sugar cane cannot be produced in Canada as it thrives in tropical regions. As a result, the very roots of the BC Sugar franchise were grounded on imports. The raw sugar at the Rogers Sugar Refinery was primarily being ordered from the Philippines and Java when the company was young.9 A1 ships, each carrying 6000 tons of raw sugar, would arrive at the BC sugar dock to be processed.10 The reliability of this imported sugar was essential for profit. In 1896, a sailing vessel from Java to Vancouver sailed for 182 days and twice as long as expected, which resulted in the refinery requiring to suspend melting for several weeks.11 As a result, Rogers and his wife went on a trip of the Orient, with stops in Japan, Saigon, Singapore and Java before arriving in Australia in search for raw sugar.

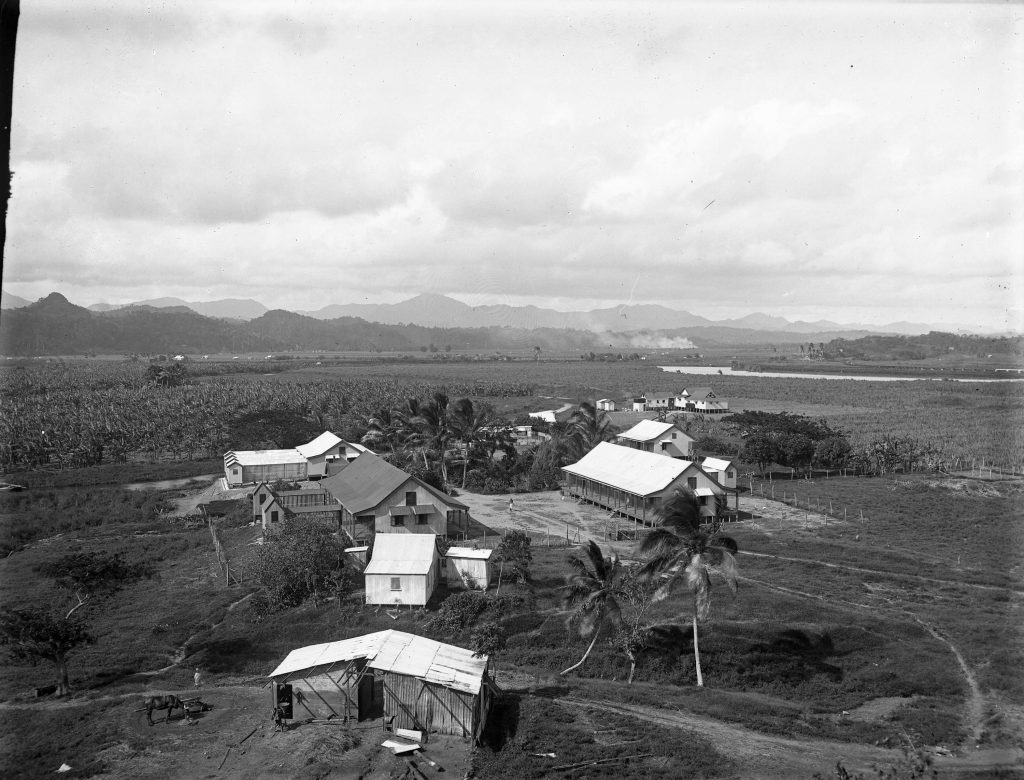

Following the tariff initiated by the Canadian government in 1898, BC Sugar began ordering raw sugar from Fiji. The preferential tariff was for goods imported by Britain and her possessions, including Fiji. With low cost and considerable reliability, Fiji eventually became BC Sugar’s major supplier. Rogers would later move into sugar production in Fiji, purchasing the 1884 Fiji Sugar Company Mill. Restorations were made to the mill, including a new hospital and mortuary, as illness and death amongst workers was a common and serious problem. The growers at the source of the raw sugar, however, were not treated well. Rogers was warned that the growers “remained alienated and were marginal. Although they live on the proverbial smell of an oily rag, a very few shillings a week being in many instances sufficient for them to subsist on”13. A continued issue faced at the Fiji plantation was securing a work force. The native Fijians refused to perform the unpleasant tasks of cultivating and cutting cane, which resulted in the Government of Fiji recruiting from India for field labour following the abolition of slavery from the previous century. These indentured workers referred to as “coolies”, were provided transportation to Fiji and preliminary housing in exchange for agreeing to work for five years at the plantation.14 Rogers took over a coolie population of 387 men, 152 women, and 90 children, peaking at a population of 1533 in 1916 when India put an end to the recruitment of indentured labour.15

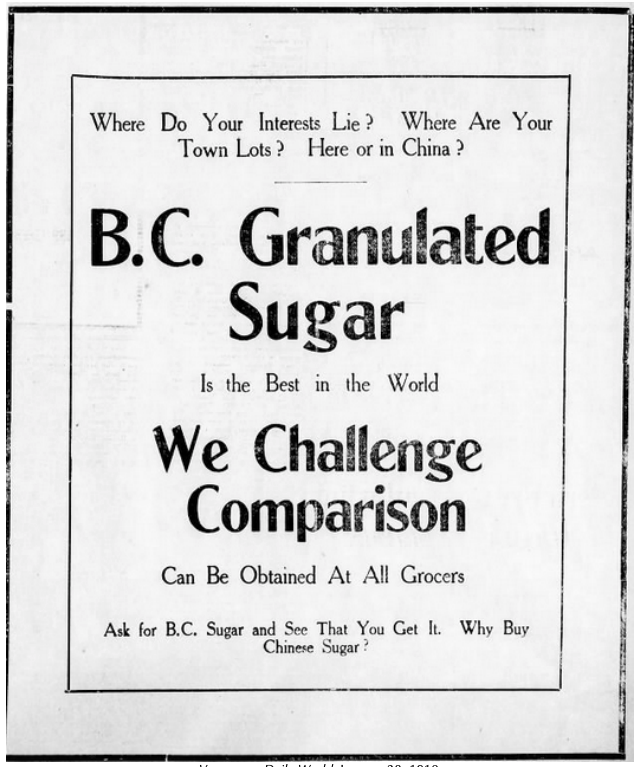

Rather hypocritically, the main reason for Rogers entering the world of sugar production to supplement his refining business was an attempt to beat out Hong Kong “coolie-refined sugar”.16 In one of Roger’s ads he states: “If you would rather buy sugar refined in Hong Kong by cheap coolie labor than sugar refined in British Columbia by well-paid white labor, then there is no further argument, but if you wish to build up your city and its prosperity, you will surely act differently and you will not allow any dealer to sell you sugar other than that which is refined right here in Vancouver.”17 Rogers seemed to have turned a blind eye on “coolie” labour in his Fiji plantation, where workers are interchangeable parts while valuing high yields above fair labour.

Rogers Wealth and Prosperity

Rogers received a sizeable directing salary for BC Sugar, as well as profit bonuses that often exceeded his salary allowing him to live a luxurious lifestyle.18 Most significantly, in 1898 Rogers purchased three lots on Davie Street at Nicola that would soon become Vancouver’s most elegant mansion.19 The two and a half storey $25,000 mansion called Gabriola was made using quarried rock from Gabriola Island and survives today as a heritage building.

Conclusion

Rogers Sugar undoubtedly shaped the City of Vancouver while feeding sweet-toothed Canadians across the country for over 115 years. B.T. Rogers founded an extremely profitable business that maximized the opportunity of Vancouver’s coastal proximity for raw sugar imports and used the Canadian Pacific Railway for transportation. The rich history and wealth of B.T. Rogers, however, would never have been possible if not for the raw sugar imports from The Philippines, Fiji, Java and Australia, where low-paid workers were bonded to the architecture of cane processing, as interchangeable parts that valued high profits above fair labour.

- Schreiner, John. The Refiners: a Century of BC Sugar. Vancouver, BC: Douglas & McIntyre, 1989. 11-13.

- Ibid. 17.

- Ibid,18.

- Ibid, 19.

- McDonald Robert A.J., Making Vancouver: Class, Status, and Social Boundaries ; 1863-1913 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000). 122.

- Waite, Donald E. Vancouver Exposed: A History in Photographs. Maple Ridge, BC: Waite Bird Photos, 2010. 166.

- Ibid, 170.

- Mackie, John. “Sugar-Coated History: BC Sugar Refinery Is Vancouver’s Oldest Industrial Site, Dating Back to 1890.” Vancouver Sun, April 6, 2011.

- Mackie, John. 152.

- Schreiner, John. 31.

- Ibid. 33.

- Ibid. 39.

- Ibid. 37.

- Michael Moynagh, Brown or White?: a History of the Fiji Sugar Industry, 1873-1973 (Canberra: Australian National University, 1981), 37.

- Schreiner, John. 41.

- Mackie, John. 154.

- Ibid. 154.

- Schreiner, John. 63.

- Ibid. 65.

Bibliography

Franklin, M. J. “Timothy Morton, the Poetics of Spice: Romantic Consumerism and the Exotic; Keith Sandiford, the Cultural Politics of Sugar: Caribbean Slavery and the Narratives of Colonialism.” English (London) 51, no. 201 (2002): 310-315.

Mackie, John. “Sugar-Coated History: BC Sugar Refinery Is Vancouver’s Oldest Industrial Site, Dating Back to 1890.” Vancouver Sun, April 6, 2011. https://vancouversun.com/news/sugar-coated-history-bc-sugar-refinery-is-vancouvers-oldest-industrial-site-dating-back-to-1890.

McDonald Robert A.J. Making Vancouver: Class, Status, and Social Boundaries ; 1863-1913. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2000.

Moore, Nikki. 2016;2017;. “Architecture, Landscape, and the Agrilogistics of Sugar in the Dominican Republic.” Architectural Theory Review 21 (3): 330-348.

Moynagh, Michael. Brown or White?: a History of the Fiji Sugar Industry, 1873-1973. Canberra: Australian National University, 1981.

Schreiner, John and Melva J. (REVIEWER) Dwyer. Schreiner, John. the Refiners: A Century of BC Sugar // Review. Vol. 23. Vancouver: British Columbia Historical News, 1990.

Waite, Donald E. Vancouver Exposed: A History in Photographs. Maple Ridge, BC: Waite Bird Photos, 2010.

Figures

1. Locations, photograph, Lantic Rogers, https://www.lanticrogers.com/en/about-us/locations/.

2. Vancouver Daily World, January 28, 1910

3. Chas E. Goad. “Fire insurance plan of the British Columbia Sugar Refining Co. Ld. Vancouver B.C.” 1899. Drawing. Modified.

4. Vancouver-Fiji Company Photographs, photograph, The City of Vancouver. https://searcharchives.vancouver.ca/vancouver-fiji-sugar-company-photographs.

5. Vancouver-Fiji Company Photographs, photograph, The City of Vancouver. https://searcharchives.vancouver.ca/vancouver-fiji-sugar-company-photographs.

6. Gabriola, photograph, the Vancouver Public Library, #1489.

One reply on “Rogers Sugar, Vancouver, 1891.”

Dear Laura,

Thank you so much for writing this article. I am working on a piece that expands the scope of the development of Roger’s Sugar to include my family history. I was born in a suburb in the lower mainland, while my parents and grandparents were born in Fiji. I’ve traced my family history back to Cawnpore, Uttar Pradesh, with the help of Dr. Marina Carter of the University of Edinburgh.

Now I’m weaving together the story of my family history, with the development of the British Empire, the ‘need’ for labor in Fiji, my families role in the development (which is nuanced), and using this story to re-frame the narrative of the development of Vancouver, as has always been a global city that has re-emerged after it’s ‘White Settler’ policy.

Thanks again for compiling this.

Akhtar (UBC 2011 Political Science and History)