Fort San Pedro is a military structure created at the height of the Spanish colonial presence in Cebu, located in the Central Visayas region of the Philippines. The project faces the Cebu strait, where it defended Spanish colonial settlements from Moro raids and conflicts with Dutch forces. As with numerous similar forts distributed throughout the islands, Fort San Pedro was intended to defend and facilitate Spanish colonialism in Cebu, through Christian conversion and the establishment of nucleated settlements. The construction of the fort and the means of its upkeep were in part determined by the power that Christianity held in shaping the attitudes of Spanish imperialism and its methods of control. The fort, in relation to the spread of Christianity as a key objective of Spanish imperialism, was a product of how missionary activity employed native labour and responded to exterior military threats during 17th century Cebu.

Coastal Conflicts

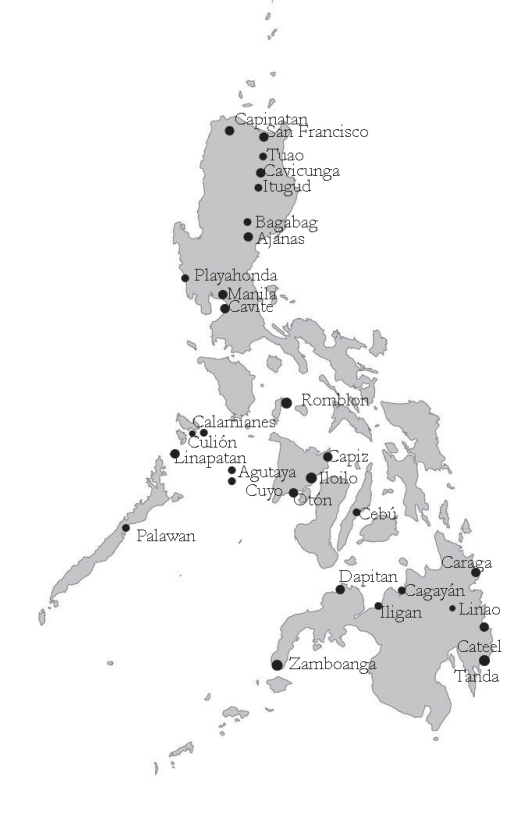

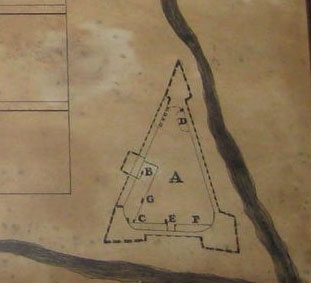

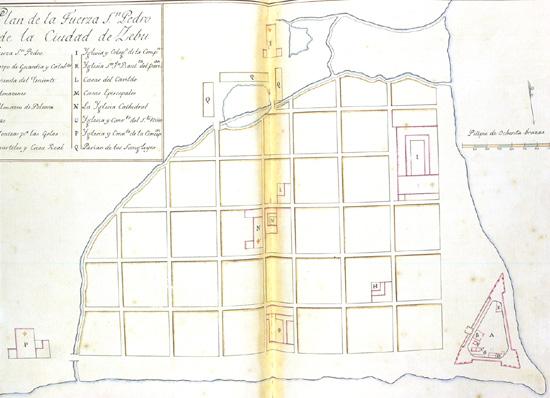

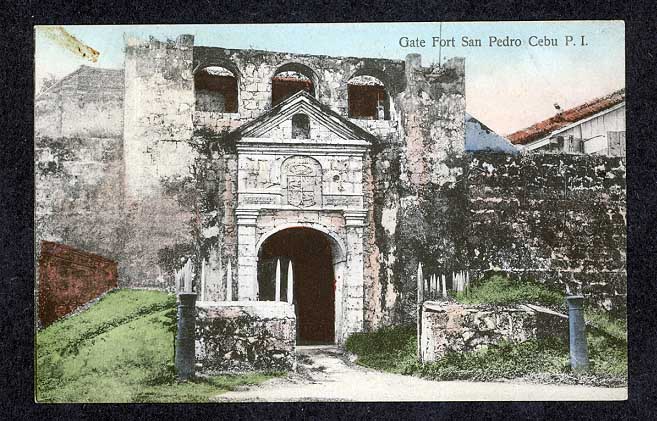

Construction on Fort San Pedro first began in 1565 with the arrival of a Spanish expedition led by Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, when it was first made of wood. The fort was only constructed with stone later, in the early 17th century, when it became necessary to defend the coast of Cebu from Moro raids and other threats to colonial Spain. Measuring over 2000 square metres of inside area with walls over six metres high, it is both the smallest and oldest triangular military defense structure in the Philippines. Two sides of the fort face the sea, where they are stationed with towers and cannons facing the water. Legazpi established the first Spanish settlement in Cebu, known as the Villa de San Miguel, which served as the centre of Spanish imperial activities in the Philippines for the first few years¹. The fort was part of a larger network of coastal bastions distributed throughout the islands, comprised mostly of smaller unconnected structures that acted to maintain commercial routes over the water. These structures were largely freestanding without other supporting buildings, built to resist attack from singular directions. Like the early construction of Fort San Pedro, they were often made of wood and were not designed for combat with Western militia in the early stages of Spanish colonialism, as local conflicts and resistance to imperial Spain were the initial concern while seizing territory².

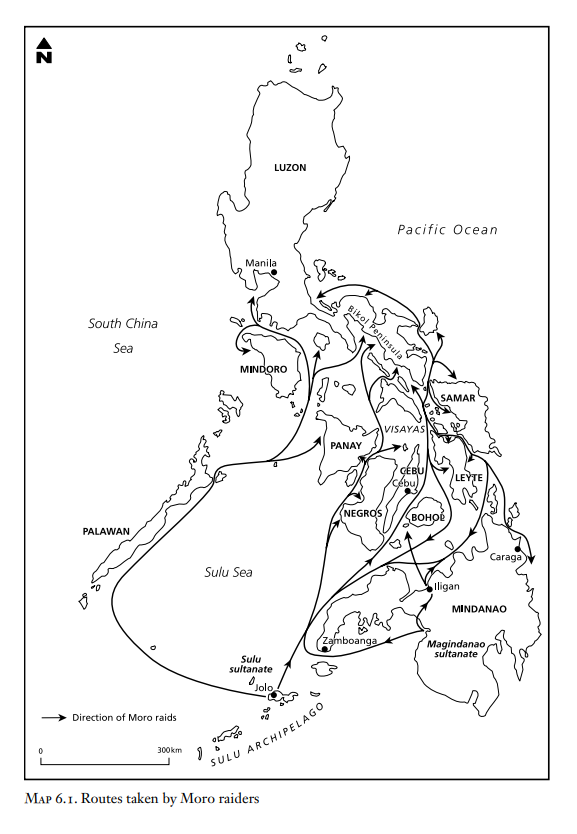

As the presence of Spain became more established in Cebu, their fears shifted towards the threat of attack by other European imperial powers seeking to sabotage commercial sea routes, as was common for many colonial powers in Southeast Asia. Consequently, Spain’s coastal forts were focused largely on the defense of their settlements and maintaining control over territories and waters. The San Pedro fort in Cebu was part of a collection of forts on various islands that helped retain Spanish control over the Sulu Sea, from example³. Most detrimental to the security and population of Spanish settlements, however, were the intermittent Moro raids that frequented the eastern Visayas. These raids occurred on an annual cycle with regular routes and struck coastal communities like Cebu, where towns were destroyed and between 700 to 1000 Filipino captives were taken each year⁴. Conflict from the Hispano-Dutch War posed further threat to Spanish settlements and native towns in the late 16th century, when Dutch forces began contesting Spain for control over land and trade routes. The establishment of the United East India Company allowed Dutch conflicts to grow in aggression, as they aimed to disrupt trade and colonize the Philippines themselves⁵. These ongoing conflicts, which necessitated the construction of Fort San Pedro and others to defend imperial Spanish settlements, influenced the population of Cebu and the activities of Christian missionaries as they sought to exercise better control over the territory.

¹Akiko Kishiue & Amano, Koichi & Cal, Primitivo & Lidasan, Hussein. The Transformation of Cebu City through the Development of its Transportation Infrastructure (1521–1990). Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol.5. October 2003

² Pedro Luengo. ” Transcultural Fights: Fortification in Southeast Asian Seas during the Eighteenth Century”, Journal of Early Modern History 23, 1 (2019): 29-66

³ ibid.

⁴ Linda A. Newson ‘Chapter 6: Wars and Missionaries in the Seventeenth Century Visayas’. Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009. 80-112

⁵ Linda A. Newson ‘Chapter 3: Colonial Realities and Population Decline’. Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009. 24-36

Imperial Spain and Christianity

Within the framework of Spanish imperialism, Christian conversion held a greater degree of importance than with other European forces. The mission of the Catholic Church, to spread Catholicism throughout a region, was a defining aspect of imperial Spain. The spread of religion was an objective in itself, beyond being an agent of imposing Western civilization or way to control native residents. Unlike the attitudes of British, Dutch or Portugese forces which prioritized commercial interests and not social transformation, Spanish conquest aimed to fully override the culture of which they were invading. The creation of Fort San Pedro, while primarily a military fort, was also in service of these social and religious interests.

In addition to being the purveyors of Christianity, Jesuits played a political role in establishing order across colonized territories. Clergy were responsible for creating a cultural network that permitted easier control of the people of Cebu: To achieve this more effectively, Jesuits offered support to Filipino communities affected by Moro raids. Jesuit support against these raids was most prevalent in the Visayas, where they organized Filipino communities to actively defend against Moro raids as well⁶. Visayan Jesuits were responsible for training local militia, constructing watchtowers and maintaining mission compounds and forts like Fort San Pedro⁷. The damage wrought by exterior threats therefore not only created military structures such as Fort San Pedro, which controlled the landscape, they also allowed Jesuits to convert and control communities with greater efficacy.

To make Christian conversion and administration more convenient, imperial Spain tried to concentrate Filipino communities into denser, permanent settlements rather than dispersed villages⁸. This was also because missionaries were distributed very thinly across the Visayas in the first four years of settlement, with clergy frequently working alone while visiting towns. In 1600, this system was changed to one where central missionary residences were established, from which clergy would travel to other towns on a rotation to preach, baptize and assist in defense⁹. Cebu was selected as one of these central residences, due to its strategic coastal location. The city became both the religious and economic capital of the Visayas in 1595¹⁰. Following the interests of imperial Spain, the Catholic Church was closely involved from the start for each of Spain’s imperial conquests, including the settlement that created Fort San Pedro¹¹. The cultural network imposed by the Jesuits, working to convert and occupy the Philippines, was enabled by the conflicts, defense and strategic harbour associated with Fort San Pedro. The fort, constructed at the very conception of the Spanish and Christian invasion in Cebu, is as much a religious agent as it is a military one.

⁶ Newson, 27

⁷ H. De La Costa. “The Jesuits in the Philippines 1581-1959.” Philippine Studies 7, no. 1 (1959): 68-97. Accessed April 22, 2021.

⁸ Newson, 27

⁹ De La Costa, 74

¹⁰ Newson, 80

¹¹ Francis B. Galasi. Jesuits in the Philippines: Politics and Missionary Work in the Colonial Setting. (CUNY City College of New York: 2014)

Reliance on local labour

Although imperial Spain and the Church intended to supplant Filipino culture, the Spanish population in Cebu was relatively low: This meant that the maintenance, defense and construction of settlements largely depended on native labour. The survival of Spanish settlements and Christian missions relied on work done by Filipinos, which generated the necessary revenue and construction needed to create defense fortifications, religious buildings and residences such as those inhabited by Cebu missionaries and Fort San Pedro. The conflicts with Moro raids and Dutch forces further exacerbated the demand for workers, while towns and populations simultaneously suffered from the damages. Cebu, in the Visayas, was among the most heavily affected by the Moro raids and the subsequent demand for forced native labour¹². The early history of Fort San Pedro’s construction, renovations and upkeep was largely built by Filipino workers. With the coast of Cebu being under regular attack, the conservation of the fort depended on such labour to reconstruct damages. The workers involved with the maintenance of Fort San Pedro were trained by European engineers in construction and technical drawing: Higher Spanish authorities could not visit the fort personally, so Filipino workers were ordered to produce and send them updated drawings of the fort¹³. They were also responsible for the reconstruction of the fort from wood to stone, in response to Moro raids. As the colonies grew, the construction of buildings and defense became more closely entwined with the exploitation and consequential depopulation of Filipino labourers. In addition to poor working conditions and insufficient wages, imperial Spain also taxed Filipino residents and drew workers from subsistence labour, which collectively resulted in shortages in money and food supply¹⁴. Clergy involved in the defense and missionary activities in Cebu, who intended to reduce the exploitative enterprising of Spanish soldiers during the conquest of the Philippines¹⁵, were also reliant on native labour and construction. The Spanish monarchy’s original intentions were to regulate working conditions, with regular hours and pay, so as to assimilate the Philippines into the Spanish empire peacefully¹⁶. However, the unexpectedly heavy reliance on native labour due to the ongoing conflicts around the waters of Cebu meant that Spanish settlements, missionary centres and military forts in Cebu could not continue without exploitation.

Fort San Pedro and its context tells a narrative of Spanish imperialism as it was exercised through religion and labour. The defense system constructed in response to coastal threats from Moro and Dutch forces was not only created from Filipino labour, but also served to defend imperial Spanish settlements physically and socially. Relief offered by Christian missionaries in response to these damages consolidated Spanish authority in the Philippines, particularly in religious and commercial capitals like Cebu. Geographically, Fort San Pedro was key to defending Spain from other European powers seeking to invade the Visayas, but its presence was also greatly in service of the Christian interests of Spanish imperialism.

¹² Newson, 30

¹³ Luengo, 37

¹⁴ Newson, 30

¹⁵ De la Rosa, Alexandre Coello. Gathering Souls: Jesuit Missions and Missionaries in Oceania (1668-1945). Brill Research Perspectives in Jesuit Studies, Vol. 1 Issue 2. Jan 2019

¹⁶ ibid.

Sources

Luengo, Pedro. ” Transcultural Fights: Fortification in Southeast Asian Seas during the Eighteenth Century”, Journal of Early Modern History 23, 1 (2019): 29-66, doi: https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/10.1163/15700658-12342628

Newson, Linda A. ‘Chapter 6: Wars and Missionaries in the Seventeenth Century Visayas’. Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009. 80-112 muse.jhu.edu/book/8333.

Newson, Linda A. ‘Chapter 3: Colonial Realities and Population Decline’. Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009. 24-36 muse.jhu.edu/book/8333.

De La Costa, H. “The Jesuits in the Philippines 1581-1959.” Philippine Studies 7, no. 1 (1959): 68-97. Accessed April 22, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42719422.

Galasi, Francis B. Jesuits in the Philippines: Politics and Missionary Work in the Colonial Setting. (CUNY City College of New York: 2014)

De la Rosa, Alexandre Coello. Gathering Souls: Jesuit Missions and Missionaries in Oceania (1668-1945). Brill Research Perspectives in Jesuit Studies, Vol. 1 Issue 2. Jan 2019. doi https://doi.org/10.1163/25897454-12340002

Mojares, Resil B. “THE FORMATION OF A CITY: TRADE AND POLITICS IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY CEBU.” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 19, no. 4 (1991): 288-95. Accessed April 22, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29792067.

Kishiue, Akiko & Amano, Koichi & Cal, Primitivo & Lidasan, Hussein. The Transformation of Cebu City through the Development of its Transportation Infrastructure (1521–1990). Journal of the Eastern Asia Society for Transportation Studies, Vol.5. October 2003.

Images

Fig. 1: Fuerza de Fort San Pedro, Public Domain, 2006

Fig. 2: Adam Daley, Inside Fort San Pedro Facing Entrance, 2010

Fig. 3: Illustration of Fort San Pedro in 1565,Public Domain, 2009

Fig.4: Map of the Philippines with locations of forts in the 18th century. Luengo, Pedro. in ” Transcultural Fights: Fortification in Southeast Asian Seas during the Eighteenth Century”, Journal of Early Modern History 23, 1 (2019). Fig.3, p39

Fig.5: Routes taken by Moro raiders. Newson, Linda A. ‘Chapter 6: Wars and Missionaries in the Seventeenth Century Visayas’. Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2009. Map 6.1. p86

Fig.6: Cdvl, Layout of San Pedro floor plan, Public Domain, 2009

Fig.7: Cdvl, Location of Fuerte de San Pedro during 1643, Public Domain, 2008

Fig.8: Cdvl, Front entrance of Fuerte de San Pedro c.1900, Public Domain, 2008