Le Château Frontenac, a Canadian pacific Railway hotel in Quebec City constructed in 1892, is often revered for being the heart of Old Quebec. Although the hotel nowadays is considered to be luxurious and picturesque, it has not always been thought of so highly throughout the past. What tends to be overlooked are the details and moments that have led up to the hotel’s existence today, as well as the near and far social implications and effects the hotel has invoked.

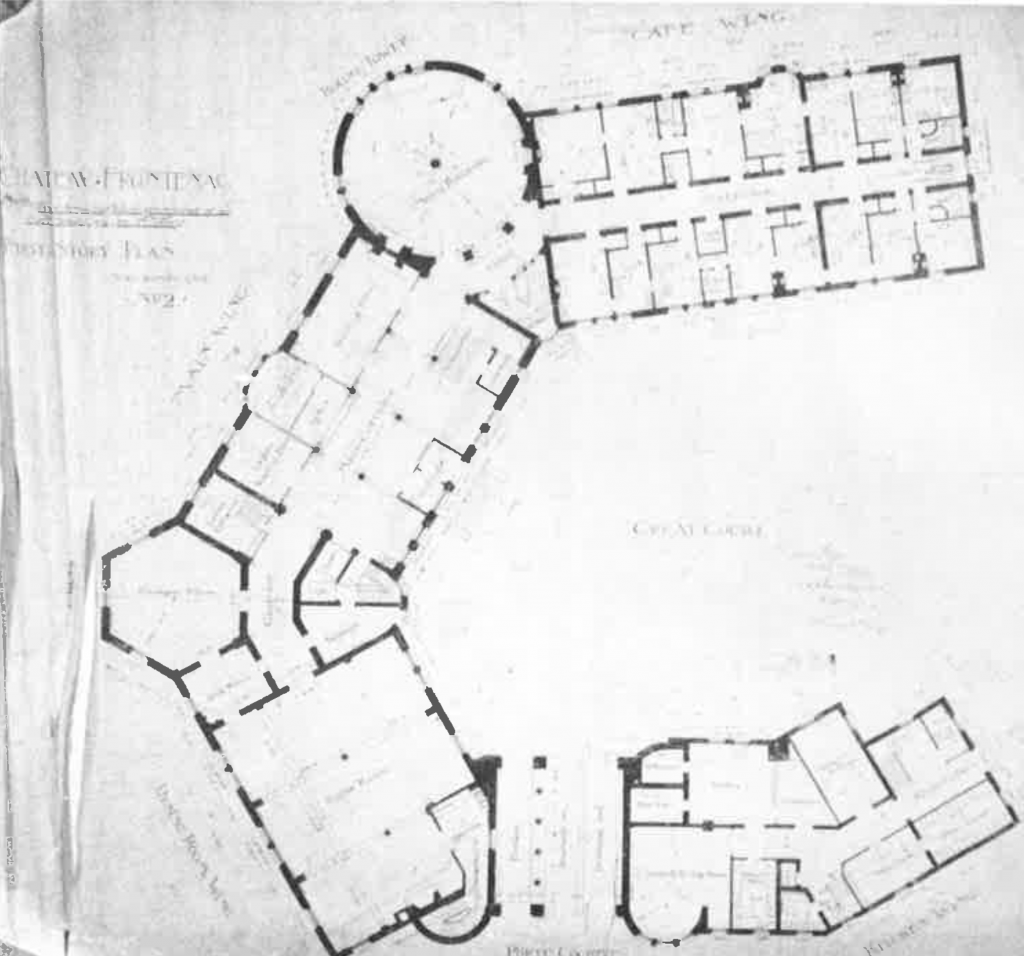

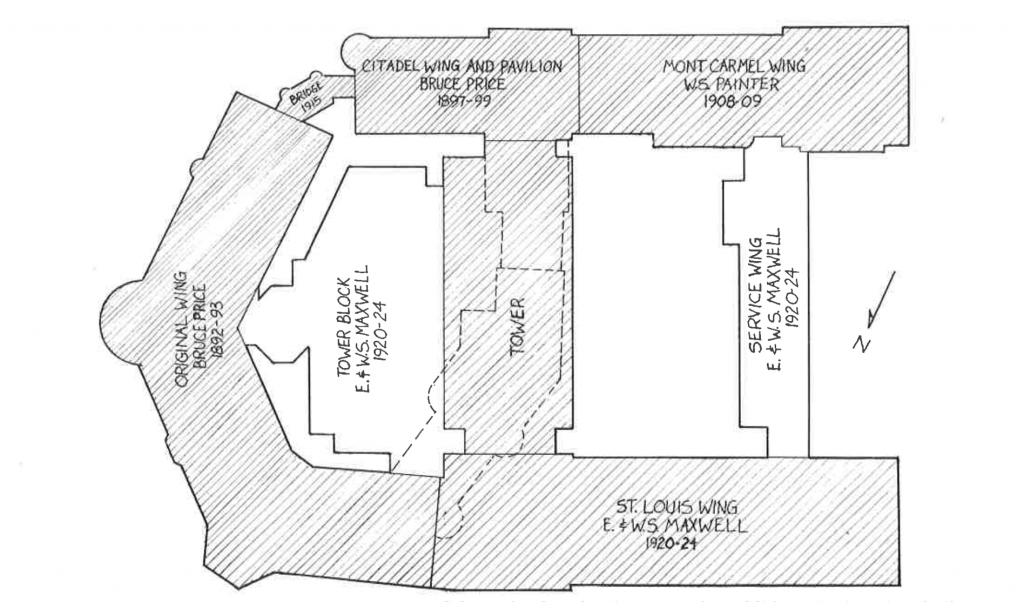

On November 7, 1885, the last spike of the Canadian Pacific Railway transcontinental line was driven into the ground, completing Canada’s first continuous track from coast to coast.1 In order for the completed line to serve the needs of the travellers and to to achieve a profit off of the infrastructure, places for temporary accommodation were the next priority. The CPR was significant to Canada because it built the nation with regards to the material connections it forged across the continent, but also because it was the very condition for Canadian confederation.2 William Van Horne, president of the Canadian Pacific Railway, initiated the development of the string of CPR hotels positioned alongside the rail line across the country. Succeeding the completion of the rail, the initial lodgings were constructed in British Columbia in 1886, followed by Alberta.3 Quebec was the next destination in the expansion of the railroad hotel system. The initial concept was to establish a castle on a cliff, promoting the construction of a luxury hotel in order to attract affluent travellers to the capital, aiding in the development of tourism.4 In 1982, a group of businessmen associated with the CPR formed the Château Frontenac Company, led by William Van Horne.5 Bruce Price, an American Architect was selected as the designer, and the hotel in Quebec City was completed in 1893. Throughout its existence, it has undergone several renovations and additions, manipulating the existing structure (Figure 2).

Beyond the superficial level, one can begin to understand the further intricacies of the Château Frontenac and how it both developed alongside and stimulated social contention. The CPR is usually dissociated from its racial logics, even though it’s associated colonization premised on the dehumanization of Indigenous people.6 Deborah Cowen writes that “whole neighborhoods – Black and working class – that came to define the political and social life of the city were built around the physical infrastructures of the rail yards, tracks and stations that constitute its physical form to this day.”7 Although often neglected, the CPR hotels become a link of establishments that are tied to racial regretful treatment. Quebec City had the locational advantage of being at the centre of the land and sea transport interface, acting as a major North American seaport at the heart of the Eastern Canada railway network. Van Horne saw it as his mission to promote the expansion of the British Empire by making the CPR part of an all-British route to the Orient.8 It is perhaps common to dissociate the racial mistreatment with the building of the CPR rail and the attraction of the CPR hotels, but they are so closely intertwined. The hotels provided an economic resource to the CPR infrastructure, attracting tourists to ride the rail and stay in the lodgings.

Another source of contention is how the style of the Château Frontenac came about and what it implies regarding the political authority and social construction of the nation. Conflict between British Protestant and French Catholic perspectives comprised the founding years of Canada as a nation. The Château style became interpreted as the architectural symbol of the alliance between the two founding peoples since it combined Scottish Baronial and French chateaux motifs.9 The hotel represents a hybrid of the two colonizers. The initial construction of Le Château Frontenac is horseshoe-shaped in plan (Figure 1), with public rooms on the first two floors. The original establishment contained space for 170 guests, with the best bedrooms placed in the main wing facing the St. Lawrence River.10 The interior contained different types of suites: the Habitant Suite, which was furnished in the style of early French Canada, an homage to the surrounding environment; the Chinese Suite, announcing that Le Château Frontenac was the first stop after Europe in the Canadian Pacific’s route to the Orient; and the Dutch suite, which honoured the Amsterdam shareholders who supported the company in the early stages.11 The different suites place emphasis on particular cultures, curated to project a distinct image to the visitors. This begins to contribute to the misalignment of perspectives with the local Quebecois citizens.

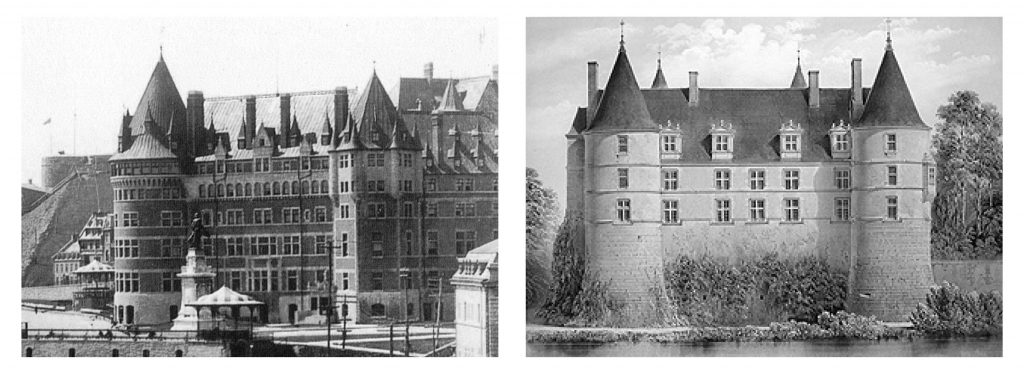

Figure 4. (right) Château de Jaligny, 1841.

Comparison of these two images reveals similarities in architectural style.

When comparing the Château to earlier precedents, parallels arise with early French architecture, particularly in Château de Jaligny from 1841.12 Further analysis of Figure 3 and Figure 4 highlight similar horizontal wall articulation featuring a tall flat facade with small windows depicting the interior units. Cylindrical forms soften the corners of the buildings with steep conical roofs complimenting the roof slope of the rest of the building. Further ornamentation extrudes off the roof with finials, establishing a sense of depth from front to back. It is often perceived that the Château and its medieval imagery were born out of a particular imperialist nostalgia for an idealized French Canada.13 Furthermore, Bruce Price was American, taking influence and inspiration from other American architects. Many of the major figures involved in the development of the Canadian railway hotels were lured from companies in the United States. A factor contributing to the growing admiration for French historical and modern design was that several American architectural students trained at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, bringing its lessons and virtues into their own practice.14

On the contrary, Price described the inspiration for the hotel to come from the local site and surrounding context, emphasizing the naturalness of the design. Considering the site the apex of the picturesque old city, it became an effortless endeavour, incorporating the building into the natural surroundings.15 In contradiction, the exterior walls are made of orange-red Glenboig brick imported from Scotland, questioning the hotel’s relation to its local context.16 Contributing to the stylistic contention, materials were sourced from outside of Canada despite the availability of local high-quality bricks. Larger-scale desires of social and political power were reflected in design decisions of the building. Scotland had a significant influence on the development of the French château style in Canada, but it became a source of social conflict for French-Canadians, demonstrating how culture, identity, and tradition were selectively created by the interplay of political, commercial, and individual forces over time.17 The design for the hotel became less about taking inspiration from the site and its surroundings, and instead imposing external perspectives onto the French-Canadian city.

Moreover, this influence had further social implications that directly affected the French-Canadian population residing in Quebec. In its early years, the hotel was targeted mainly towards Anglo-Saxon tourists, becoming a source of resentment and exclusion to some French-Canadians. The main language spoken inside the hotel was English, which conflicted with the local French inhabitants. The guest ledger reveals that for the first year of operations, there was a near total absence of French-Canadian names amongst the guest registrants.18 Many tourists were attracted from the Eastern coast of the United States with an influx during the summer months to escape their summers.19 The interior workings of the hotel featured discriminatory employment practices, with English-Canadians or Americans holding the highest managerial positions.20 The French culture that the hotel was attempting to project was not the hybridized culture of the Quebecois population, but instead a purified version that was carefully selected to project aspects of the local culture that mesh with the Château’s image.21

By delving into the specifics of Le Château Frontenac’s history, one can begin to understand the social and political implications and contestation, reflecting the British and French colonial strife.

Notes

1 Kalman, Harold D. “The Railway Hotels and the Development of the Chateau Style in Canada.” 1986. 5.

2 Cowen, Deborah. “The jurisdiction of infrastructure: circulation and canadian settler colonialism.” The Funambulist, (17), 2018, 14-29.

3 Kalman, Harold D. “The Railway Hotels and the Development of the Chateau Style in Canada.” 1986, 6.

4 Morgan, Joan E. “The Castle of Quebec.”

5 Kalman, Harold D. “The Railway Hotels and the Development of the Chateau Style in Canada.” 1986, 11.

6 Cowen, Deborah. “Following the infrastructures of empire: notes on cities, settler colonialism, and method.” Urban Geography, 41:4, 2020, 472.

7 Ibid., 473.

8 Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. “The Chateau Frontenac in Quebec City: The Social History of an Icon.” The Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, 2004, 53.

9 Liscombe, Rhodri W. “Nationalism or Cultural Imperialism?: The Château Style in Canada.” Architectural History, (36), 1993, 127.

10 Kalman, Harold D. “The Railway Hotels and the Development of the Chateau Style in Canada.” 1986, 12.

11 Ibid., 14.

12 Ibid., 13.

13 Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. “The Chateau Frontenac in Quebec City: The Social History of an Icon.” The Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, 2004, 53.

14 Liscombe, Rhodri W. “Nationalism or Cultural Imperialism?: The Château Style in Canada.” Architectural History, (36), 1993, 133-134.

15 Sturgis, Russell. “The Works of Bruce Price.” The Architectural Record, 1890, 82.

16 Kalman, Harold D. “The Railway Hotels and the Development of the Chateau Style in Canada.” 1986, 12.

17 Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. “The Chateau Frontenac in Quebec City: The Social History of an Icon.” The Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, 2004, 51.

18 Ibid., 55.

19 Lundgren, Jan O.J. “The Market Area of the Turn of the Century Hotel: The Château Frontenac in Quebec City.” Recreation Research Review, October, 1983: 11-16.

20 Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. “The Chateau Frontenac in Quebec City: The Social History of an Icon.” The Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, 2004, 56.

21 Ibid., 56.

Bibliography

Broudehoux, Anne-Marie. “The Chateau Frontenac in Quebec City: The Social History of an Icon.” The Society for the Study of Architecture in Canada, 2004: 51-62.

Cowen, Deborah. “The jurisdiction of infrastructure: circulation and canadian settler

colonialism.” The Funambulist, (17), 2018: 14-29.

Cowen, Deborah. “Following the infrastructures of empire: notes on cities, settler colonialism, and method.” Urban Geography, 41:4, 2020: 469-486.

Kalman, Harold D. “The Railway Hotels and the Development of the Chateau Style in Canada.” 1986: 5-47.

Liscombe, Rhodri W. “Nationalism or Cultural Imperialism?: The Château Style in Canada.” Architectural History, (36), 1993: 127-144.

Lundgren, Jan O.J. “The Market Area of the Turn of the Century Hotel: The Château Frontenac in Quebec City.” Recreation Research Review, October, 1983: 11-19.

Morgan, Joan E. “The Castle of Quebec.”

Sturgis, Russell. “The Works of Bruce Price.” The Architectural Record, 1890: 82.

Images

Cover Image: Historic Hotels Worldwide. Accessed April 26, 2021. https://www.historichotels.org/hotels-resorts/fairmont-le-chateau-frontenac/history.php

Figure 1: Kalman, Harold D. “The Railway Hotels and the Development of the Chateau Style in Canada.” 1986: 35.

Figure 2: Kalman, Harold D. “The Railway Hotels and the Development of the Chateau Style in Canada.” 1986: 39.

Figure 3: Fairmont Hotels & Resorts. Accessed April 24, 2021. https://www.canadiangeographic.ca/article/six-notable-moments-chateau-frontenacs-125-year-history

Figure 4: Victor Petit Chateaux of the Loire Valley 1841. Accessed April 25, 2021. https://www.panteek.com/Petit/