Sir John Soane was a prominent neo-classical architect in Britain between the 18th and early 19th century. Possibly his most famed building was the London townhome he inhabited during the latter half of his career. Having begun its renovations in the early 1800’s, Soane lived and worked at Lincoln’s Inn Fields until his death in 1837. During this time, his home grew and transformed as an archive of his projects and his expansive art collection. As this collection grew, the original townhome expanded into two adjacent townhomes, filling them with a complexity of spaces and things.[1]

Before Soane’s death, he legally preserved his home as a public museum to cement his life’s work into architectural history.[3] As a result, it became one of the first public institutions of a private space, and subsequently a model of the gentleman’s domestic interior.[4] The Sir John Soane Museum is widely studied and visited today and was equally popularized as it opened as a museum in 1837. Remarkably, it has been introduced to us in multiple courses during our design program, and thus remains an active participant in modern architectural education. Its mysteries are still shared amongst students and professionals of architecture, remaining a highly original precedent 200 years into the future. The glorification of this museum can be attributed to both its spatial complexities and the fragmented staging of historical artifacts in a domestic space, rather than in a traditional institution. As such, because the house-museum remains a place of education, does it also influence acts of colonialism invisible to the eye? Alternatively, does the fracturing of history and time emphasised by its architecture disrupt the European canon of architectural history and thus present opportunities to decolonize such institutions today? To facilitate this debate, this paper will focus on the architecture and collection of the museum’s interior to unravel its effects as an educative tool of architectural history.

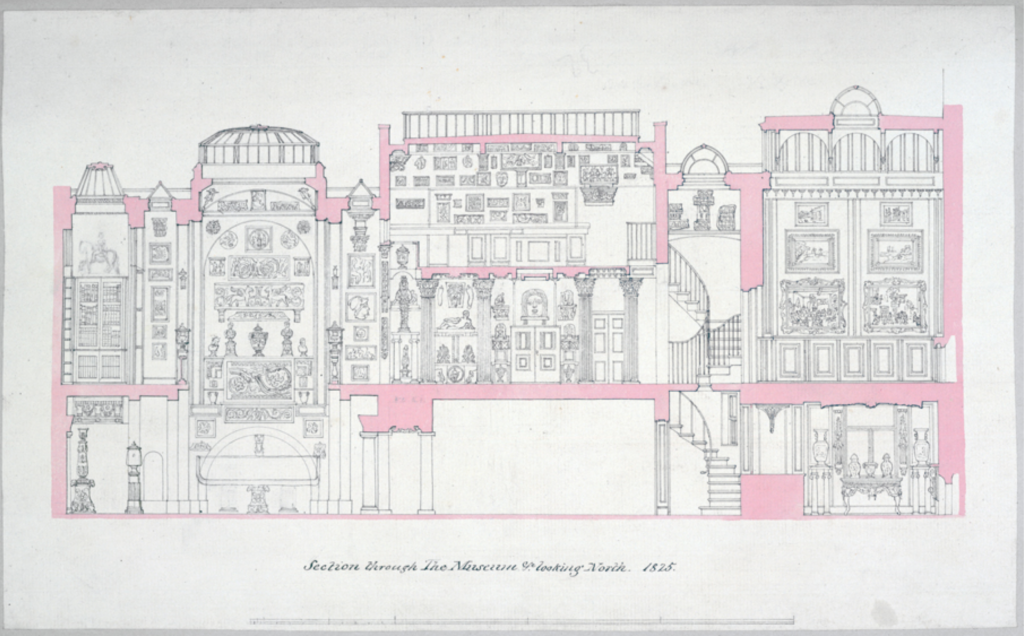

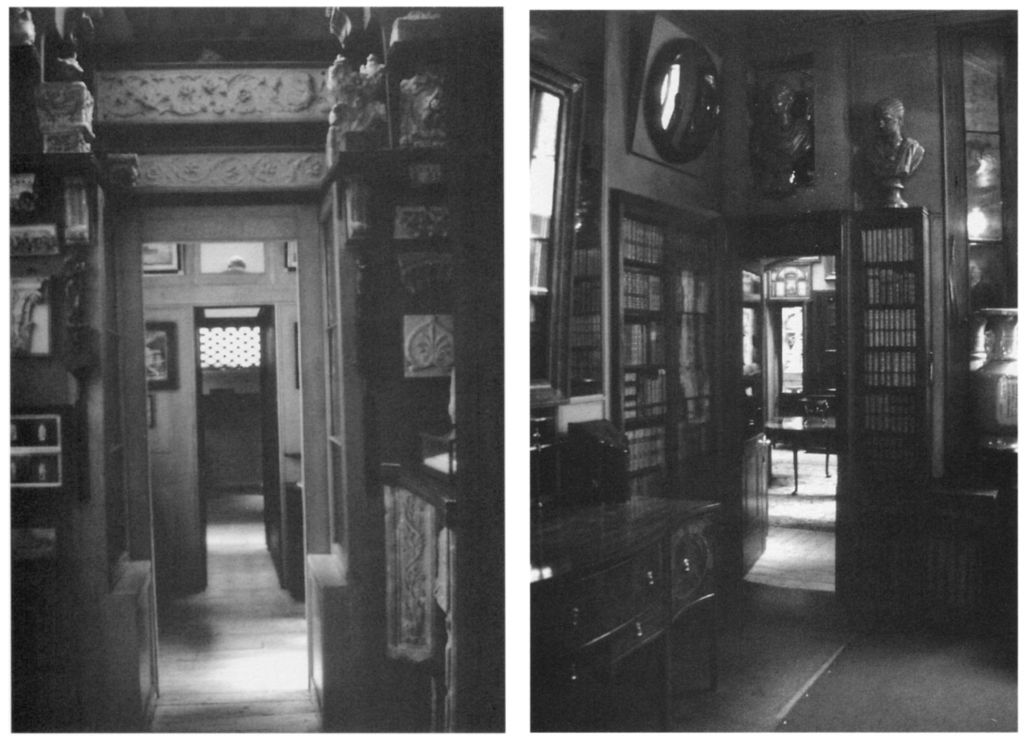

At the house-museum, Soane was known to entertain guests and support architectural studios from the Royal Academy where he was a professor of architecture.[5] Soane, an enthusiast of the sublime and the picturesque, adopted these landscape theories into his interior architecture language.[6] Soane was famed as a magician of space who curated his collection as a theatrical experience for the viewer.[7]As an architect with a background in drawing conventions, he adopted many of these traditional vantage points (section, perspective) into the architecture. He played with varying levels of floors with openings and vertical site lines that suggested a continual unfolding space.

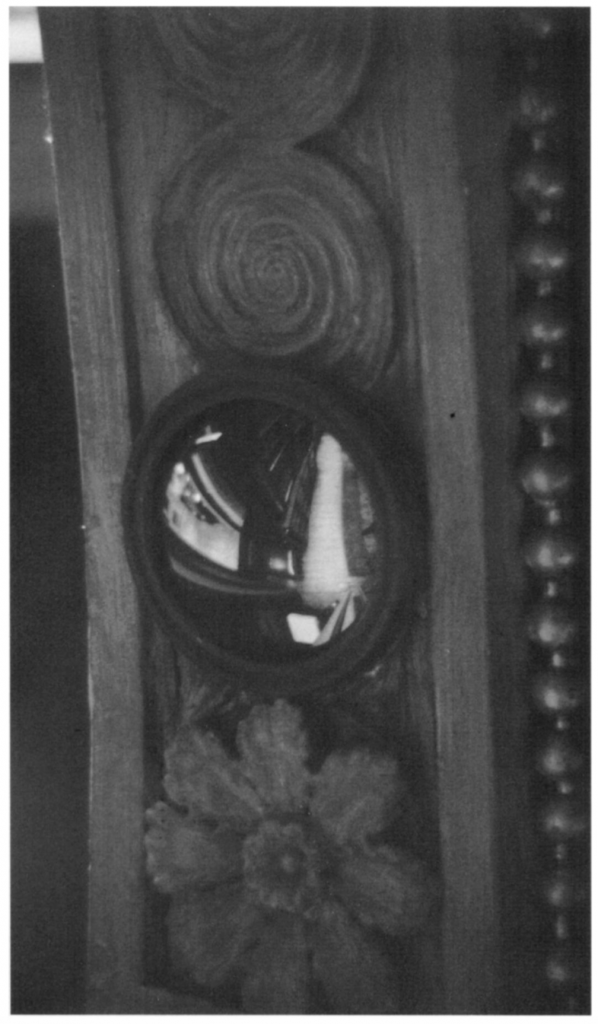

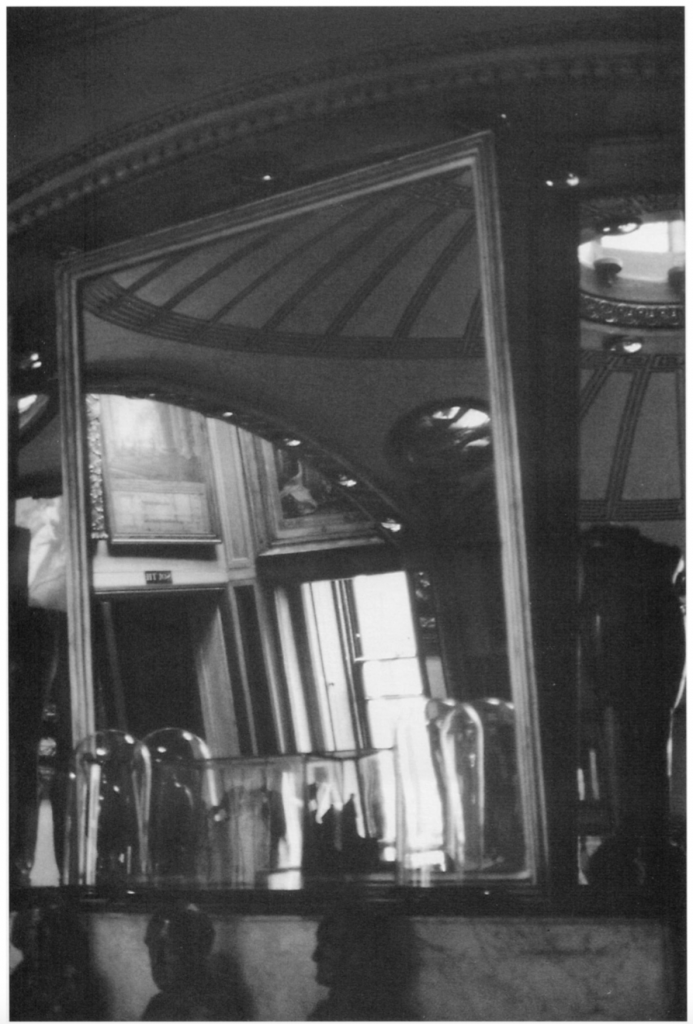

The openings to the lower crypt and above the mezzanine studio cast patterns of light and shade throughout. He further framed unfolding perspectival views with narrow hallways and moving walls and used mirrors to direct the visitor and isolate objects amongst the collection. Mirrors were commonly used by landscape painters of the time and were gaining popularity in the recreational activity of nature tours. Participants would use mirrors to frame and prospect certain landscape views and capture sublime moments of light just as their favorite landscape artists would have.[9] As an admirer of this art movement, Soane used mirrors to fragment and disorient these historical objects from their traditional lineage. As a result, varying themes of time can be drawn from the museum, and mirrors helped facilitate this fragmentation. In the house, Soane used a mix of convex and angled mirrors and positioned them in archways and along the walls. Helene Furján writes in the Specular Spectacle of the House of the Collector, “These mirrors proffer up a miniaturized (and thus collectible) image of the world of the viewing subject”, and the convex image provides a “coordinated world” reduced to the scale of comprehension.”[10] Furján suggests that Soane used mirrors not only to reflect light but to also simplify a view in a disorienting and dense space.

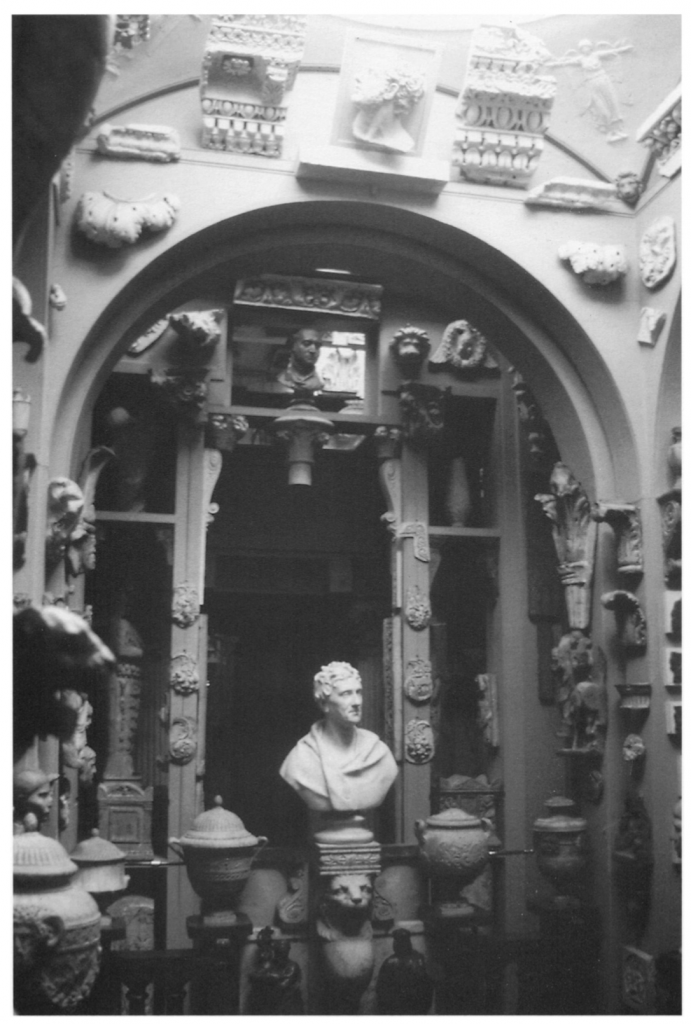

The collection organized in this way includes a mixture of old and present (at the time) artifacts that demonstrated Soane’s interests in architectural history. Included in the collection are paintings from the romantic era, a collection of books, hundreds of castings of sculptures, columns and ornament from classical Greek and Roman buildings, artifacts such as a sarcophagus from ancient Egypt, and cork and plaster models of Greek and Roman ruins he visited throughout his tour of Europe.[13] Even in the architecture supporting the collection, Soane mimicked fragments of columns, staircases, archways, and vaulted ceilings of famed Roman, Greek and Englishbuildings. Amongst the collection, Soane placed his own work throughout the museum, including over 60000 of his drawings and hundreds of his models. [14] The display of this collection was a theatrical performance that solidified his cultural and aesthetic tastes and status as a gentleman. [15] It secured his neo-classical style into the history of architecture while also promoting the arts in Britain. The image of a sculpture of Soane centered amongst fragments of history says a lot about how he viewed his contributions to the history of Architecture and how he viewed the house-museum as a learning tool past his death. Even before he passed, the house-museum operated as a library, of which his students could explore and sketch the artifacts of the world all in the confines of their studio. [16]

A by-product of the picturesque is that it ‘souvenirs’ the natural world and constructs a simplification of its story to be read out of context. It also severely alters any sense of distance and time between these places and cultures. The house-museum is described by Helen Furján as a cabinet of curiosities, a collection of mementos from around the world. The architectural staging of these mementos is largely inspired by the picturesque and thus actively appropriates these cultural artifacts into a history constructed by Soane. As a device of education, and a model of a gentleman’s interior, this influenced the collecting of things at a wide scale. Walter Benjamin describes in Paris, Capital of the world that near the end of the 18th century the interior became a place separated from work, where ‘man’ could indulge in fantasies of a better world. He writes, “In the interior, he brings together the far away and the long ago. His living room is a box in the theatre of the world.”[18] Benjamin believed the interior universe of the individual also left traces of domesticity, and that over time these traces of life wove into their collections, becoming an expression of personality.[18] The staging of Soane’s collection in his domestic space captures the essence of society in this period and his imagination of it. Entering the museum is much like entering a time capsule sending you back to Soane’s interior world, one that is encouraged by the museum’s architecture to appropriate and fantasize the fragments of the past. This ambition of Soane was a sign of architecture freeing itself from a set of past rules or hierarchies passed on through generations of history telling, and shifting into something more artistic, personal, and imaginative. Furján expresses this as, artistic genius. She suggests the museum was a moment when artistic genius, first associated with romantic art, shifted into design. [19] She writes, “Soane’s own house instrumentalizes his views on style: placing the production of this ‘new language’ within the context of its classical origins.”[20] As a place of education, the house-museum is organized as a celebration of history. The sarcophagus, urns and tomb in the basement crypt are layered beneath the teaching studio and Soane’s neo-classical work on the above floors, suggests as Furján explains, that Soane celebrated his British neo-classical style as a rebirth of the classical.[21]

Visiting Soane’s museum in the time of 19th-century modernity, greatly inspired a culture of collection that made it possible to own souvenirs of the world within a domestic space, a time when collecting became a way of symbolizing wealth and status.[23] This suggests acts of colonialism not only occurred in world fairs or overseas but infiltrated the domestic spaces and culture in Europe. This domestic practice of collecting and commodifying fragments of the world would also have been influenced by museum collections throughout Europe and the New World. However, it is unclear if Soane’s intentions were purely for social status and preserving of his legacy. Alternatively, they could have been positioned to disrupt the invented European history of Architecture by displaying them untraditionally in a domestic space. His house-museum could suggest a shift in architectural hierarchy, leaving visitors inspired to participate in architectural discourse in their domestic environments. Did the Sir John Soane Museum cause the erosion of a highly privileged and elite discipline to become attainable to non-professionals and lower classes?

The untraditional curating of the collection certainly suggests so. The collection ignored the traditional practice of grand displays against monotone backgrounds, diffuse lighting and was neither organized chronologically. Rather, it was designed in a domestic interior as a picturesque and sublime experience of space. The collection mostly of sampled fragments of history, (castings and plaster molds of the real thing) were dispersed throughout, inviting a more affordable hobby of collecting. In a time without electrical light – natural light, candles, and mirrors were used to cast light into the shadowy corners of the house. The density of sculptures, paintings, and architectural ornaments intertwined with domestic objects such as furniture, carpets, and wallpaper, created a series of dense spaces that evoked an imaginative journey throughout the house-museum. This formed a more exciting and less aristocratic enjoyment of art. Visitors were given a taste of how to design their interiors and promote their gentlemanly identity to their visitors and friends. In many ways it is similar to curating a social media page.

Soane believed that architecture had a role similar to the arts. It could elicit emotion, experience and most of all engender imagination. The distortion of these spaces allowed creativity and imagination to appropriate history.[25] This suggests why the Sir John Soane Museum remains such a highly studied precedent in the discipline of architecture. The museum is no less a home than a museum and is free to visit by the common person. The collecting of things from faraway places has continued over centuries, allowing one to imagine positioning oneself at far distances, experience foreign places or ancient cultures within a fabricated interior fantasy. A fantasy that places the individual at the center of the universe. However, it also raises concerns with colonial patterns continued today. The trend of collecting souvenirs from exotic cultures and displaying them in one’s home is surely both an act of appropriation and as well, a subtle participation in the colonial practice of commodifying other cultures, animals, and races. It shows a significant privilege that the colonizer can even go to a faraway culture and bring back with him or her various goods or replicas to then be put on display.

Inside Soane’s house-museum is an internalized example of the issues of history, where the past can be staged with fragments of physical evidence and reconstructed with those projections into the present. The house-museum therefore reveals that Soane recognized the gaps of information forgotten in the past and the fictionalization of history in the present. He gathered fragments of history that inspired him and his current architectural style. In doing so, a subjective interpretation and representation of history is displayed. This is what makes it a precedent closely tied to the conflict of designing colonial architectural history courses today. History, in general, is problematic in its accuracy, as it is largely based on ‘his story’ and as such is a fragmented storytelling from a subjective interpretation and retelling of evidence available. The collecting of souvenirs in private spaces and likewise in museums, exposes these limitations. As such, appropriations of cultures persist that students of the present should be wary of both in places of education and in domestic representations. Only by looking at these critically can one begin to deconstruct history telling (in its varying displays) and begin any kind of de-colonization process.

Citations:

Benjamin, Walter and Rolf Tiedemann.The Arcades Project. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press, 1999.

Furján, Helene. Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater. Abingdon: Routledge, 2011.

Furján, Helene. “The Specular Spectacle of the House of the Collector.” Assemblage, no. 34 (1997): 56–91.https://doi.org/10.2307/3171253.

“Soane, John. Description of the House and Museum on the North Side of Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields, the Residence of Sir John Soane. London: Printed by James Moyes (1832).

Understanding Architectural Drawings.” Sir John Soane’s Museum, September 25, 2020. https://www.soane.org/collections-research/key-stories/understanding-architectural-drawings.

[1] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.1-2.

[2] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.41.

[3] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.1.

[4] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.25.

[5] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.28.

[6] Helene Furján, “The Specular Spectacle of the House of the Collector,” Assemblage, no. 34 (1997): pp. 69

[7] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.19.

[8] “Understanding Architectural Drawings.” Sir John Soane’s Museum, September 25, 2020. https://www.soane.org/collections-research/key-stories/understanding-architectural-drawings.

[9] Helene Furján, “The Specular Spectacle of the House of the Collector,” Assemblage, no. 34 (1997): pp. 69.

[10] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.60.

[11] Helene Furján, “The Specular Spectacle of the House of the Collector,” Assemblage, no. 34 (1997): pp. 77

[12] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.96.

[13] Soane, John. Description of the House and Museum on the North Side of Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields, the Residence of Sir John Soane. London: Printed by James Moyes (1832).

[14] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.19.

[15] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.26.

[16] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.28.

[17] Helene Furján, “The Specular Spectacle of the House of the Collector,” Assemblage, no. 34 (1997): pp. 84

[18] Walter Benjamin and Tiedemann Rolf.The Arcades Project. (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press, 1999): pp.9.

[19] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.83.

[20] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.13.

[21] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.164.

[22] Helene Furján, Glorious Visions: John Soane’s Spectacular Theater (Abingdon: Routledge, 2011) pp.95.

[23] Walter Benjamin and Tiedemann Rolf.The Arcades Project. (Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press, 1999): pp.8.

[24] Helene Furján, “The Specular Spectacle of the House of the Collector,” Assemblage, no. 34 (1997): pp. 75.

[25] Helene Furján, “The Specular Spectacle of the House of the Collector,” Assemblage, no. 34 (1997): pp. 83