On the outskirts of London, UK, lies Kew, home to the Royal Botanical Garden and its Palm House conservatory. This significant glass house was designed by Decimus Burton and constructed by Richard Turner from 1844 to 1848, although there has been some debate as to who rightfully lays claim to the design1. The Palm House was inspired by similar conservatories that came before it but was the largest building of its kind when it was constructed. It’s large size served to expand the possibilities of this construction method and quite possibly inspired future more ambitious projects like the Crystal Palace designed by Joseph Paxton2. The Kew Gardens Palm House was constructed in a period where prefabricated iron construction was changing architecture and building design forever with its high strength and ability to be manufactured on a large scale. The many ways in which this new construction method could be put to use were developed alongside and after the Palm House, and shifted many aspects of European society from industrial factories to museums to shopping centres and markets. This new construction method was closely linked with the colonial implications of climate control and international trade. The glass house building typology was a testing ground for new building technologies that allowed for the eventual commercialization and commodification of colonized cultures and environments. The Palm House at Kew Gardens was a prime example of this testing at play as well as an example of how glass houses and their absolute control of colonized environments and flora were used as a symbol of British Imperial power.

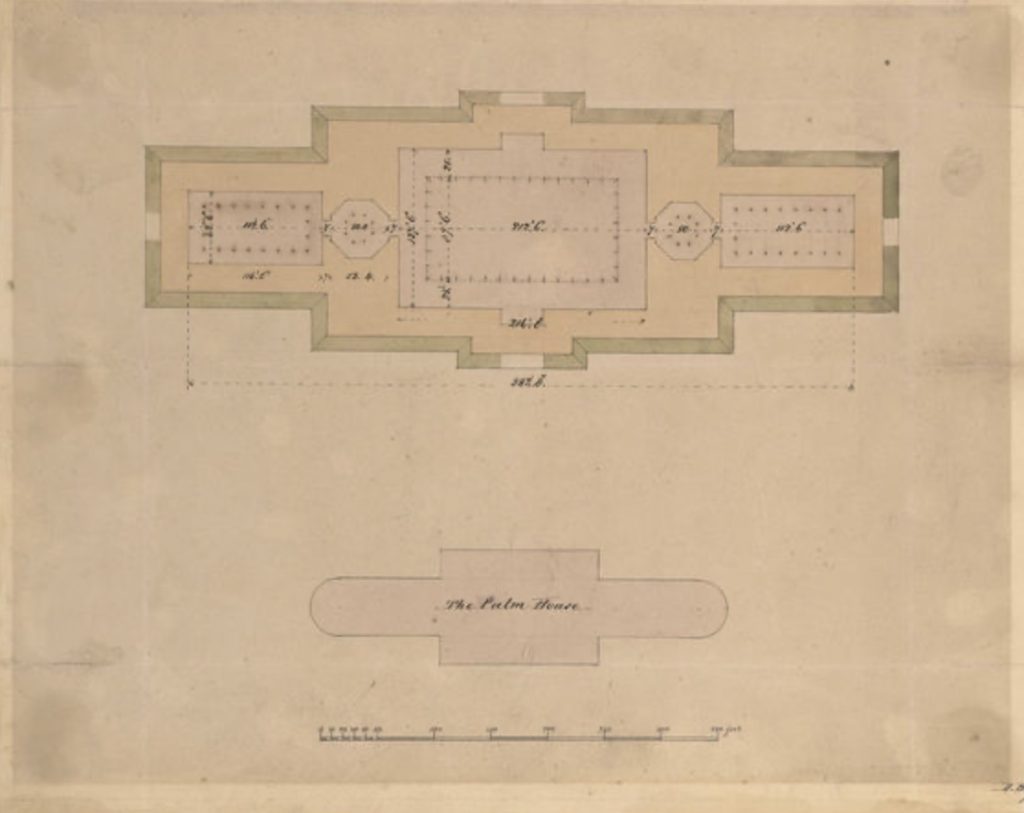

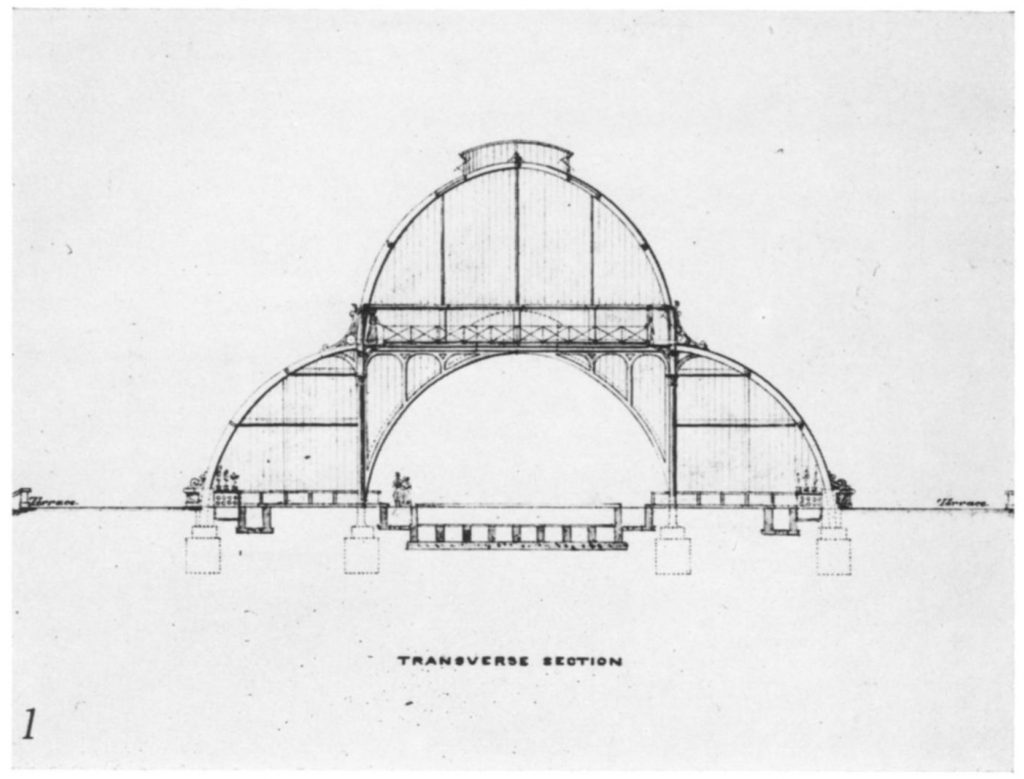

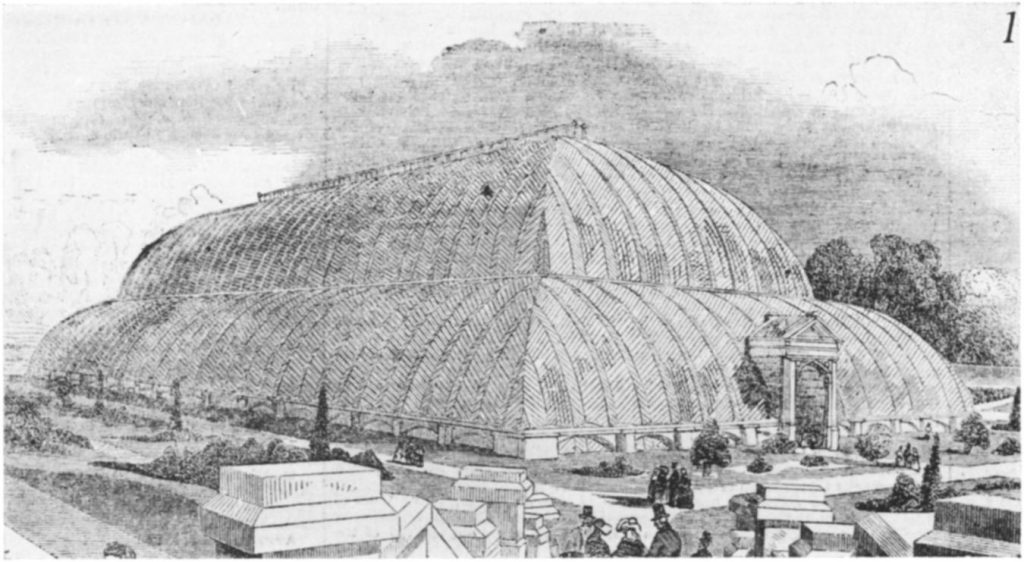

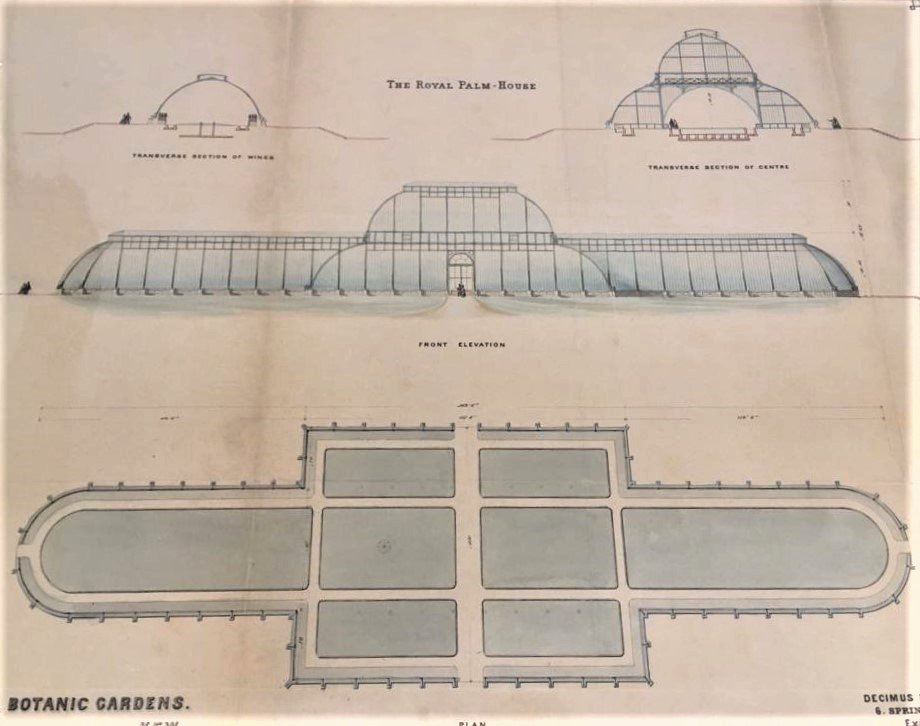

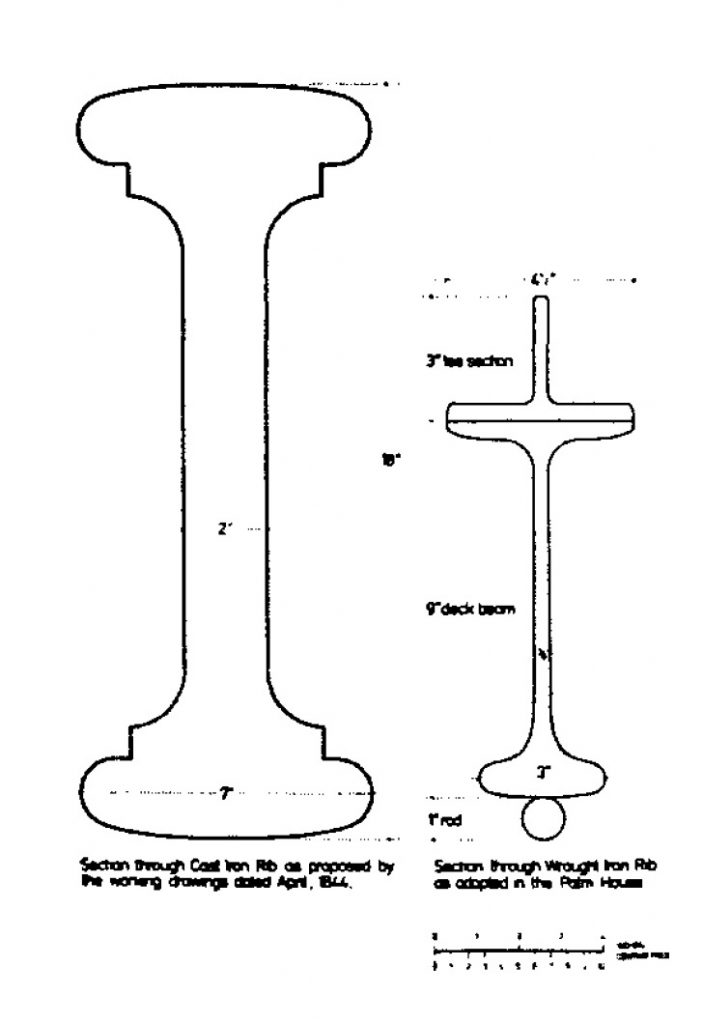

The Palm House is one of the larger buildings at Kew Gardens, rivalled only by the another nearby glass house designed by Decimus Burton called the Temperate House (figure 1). The form of the Palm House takes clear inspiration from that of the Great Conservatory at Chatsworth designed by Joseph Paxton with its curved semi circle walls creating a bubble like form (compare figure 2 and 3). The former work of Richard Turner, such as the Killikee Conservatory (figure 4), can also be seen in the design of the Palm House with its elongated plan centred on a prominent dome to accommodate the tallest plants (figure 4). It was constructed from a combination of cast and wrought iron members and glazed in glass. The design of the members was specially formulated for this building however the technology used was developed by the ship builders James Kennedy and Thomas Vernon. It involved the use of the innovation of rolled wrought iron “bulb tee” deck beams, the modern equivalent of which is a steel I beam.3 For the Palm House, the design of these members was modified to include ornamental aspects as well as flanges to secure the glazing (figure 5). Being a conservatory designed to grow plants suited to warmer climates the Palm House also had an extensive heating and ventilation system designed by Richard Turner.4 This was perhaps the most important part of the building and definitely one of the most important lasting effects that this building typology had on the world of architecture in a colonial context. The developments in heating and ventilation required to create artificial climates in the glass houses of this industrial era were precursors to more comprehensive climate control used in architecture which facilitated extended colonial control over tropical climates and cultures.5

1 R. G. Desmond, “Who Designed the Palm House in Kew Gardens?,” Kew Bulletin 27, no. 2 (1972). doi:10.2307/4109457.

2 D. Valen, “On the horticultural origins of Victorian glasshouse culture,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 75, no. 4 (2016): 417, doi:10.1525/jsah.2016.75.4.403.

3 “Richard Turner and the Palm House at Kew Gardens,” in Structural Iron 1750–1850, ed. R.J.M. Sutherland (Routledge, 1988), 90.

4 “Richard Turner and the Palm House,” 93.

5 Dustin Valen, “Imperial Atmospheres: Race and Climate Control on the Niger,” ABE Journal, no. 17 (2020): 5, doi:10.4000/abe.8106.

The colonial implications of the rudimentary forms of climate control developed in 19th century glass houses like the Palm House did not just come into play through later developments in technology but existed from their very inception. Much in the same way that museums like the South Kensington Museum served to reinforce British Imperial power by taking objects from British colonies and displaying them to the British public6, glass houses such as the Palm house at Kew Gardens were places where British colonial power could be displayed by showing control over the very climate and vegetation of its colonies. The ways in which the South Kensington Museum supported the British Colonial project was to display objects from colonized countries in a manner akin to trophies of conquest, communicating the extent of British Imperial control to all who visited its exhibits.7 Colonial displays in museums like the South Kensington Museum also served to create commercial interest in the materials and products of the British colonies, effectively promoting the commodification of cultures as seen by the eye of the colonizer.8 I would argue that this narrative was played out and expanded in the victorian glass house. These glass houses allowed British gardeners to dominate and control nature to benefit the British Empire both socially and economically.9 The act of taking plants from warmer colonies and displaying them in Britain to the public is a direct parallel to the act of taking culturally important objects and displaying them in British museums. In each scenario the object or plant is taken out of its natural environment and displayed how the European colonizer thinks it should be displayed, that is to say without the knowledge of the intricacies and culture and ecosystem that the object and plant belong to respectively. This contributes to harmful imaginings such as that of the “Orient” or colonized other.10 The colonial implications of British Imperial power over colonized climates was twofold; the innovation of the glass house in 19th century Britain allowed tropical climates to be effectively recreated and controlled outside of their natural location however a more disturbing effect of innovations in climate control is when the opposite situation is created.

The form of climate control that was created and improved within the Palm House at Kew Gardens in the mid 1800s was not the HVAC systems we know today but it was the beginning of the concept. Propelled by fears of airborne disease in tropical climates, the drive for colonial expansion, and innovations in climate control in buildings like the Palm House there was interest in attempting to recreate the European climate in tropical colonies.11 This was pioneered in a British government supported expedition to the Niger River in which two ships were outfitted with climate controlled rooms to protect the white men on the expedition from illnesses such as malaria that at the time British scientists believed was airborne.12 This new kind of climate control, pioneered for this exhibition by Scottish physician, chemist, and ventilation engineer David Boswell Reid13, allowed British scientists to use the air they inhabit as a way to implement hierarchies of race and power in colonial settings.14 This early use of climate control was a extension of the ideas formed in glass house design and shows the origins of the technology we have today along with its colonial implications.

6 Tim Barringer and Tom Flynn, “The South Kensington Museum and the colonial project,” in Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum (London: Routledge, 2012)

7 “The South Kensington Museum,” 11.

8 “The South Kensington Museum,” 12.

9 “Victorian glasshouse culture,” 406.

10 “The South Kensington Museum,” 16.

11 “Imperial Atmospheres,” 3.

12 “Imperial Atmospheres,” 5.

13 “Imperial Atmospheres,” 6.

14 “Imperial Atmospheres,” 5.

The innovations in iron and glass construction technology that were made during the construction of the Palm House and other glass houses like it helped to develop many forms of iron and glass buildings during the 1800s. With their requirements for large spans and thin members for maximum daylighting, glass houses pushed the boundaries of what architects and iron workers thought was possible at the time. With its large scale and construction in the first half of the 1800s, the Palm House was an early example of the possibilities of the relatively new building material that was cast iron. A number of important ferrovitreous building typologies developed alongside and after the glass house typology, most pertinent to the context of this paper are the market hall, arcade and finally the department store.15 The importance of these buildings in connection to glass houses is the roll that they play in the beginning of a culture of commerce in Britain.16 Market halls were an evolution of the traditional open air food markets and served as a central place were citizens of European municipalities could gather to buy and sell meat and produce. In combination with the retail equivalent in arcades, and later department stores, these building types served the same role as modern supermarkets and can even be considered the origins of the malls and big box stores we frequent today.17 The commercialized shift in culture that iron construction helped to bring about was the beginning of the demand for globalized trade, a system that has and continues to support and profit from colonial extraction economies.

The Palm House at Kew Gardens was the largest glass house of its time and is a prime example of a building typology and construction innovation that had deep and multifaceted ties to colonialism. The Palm House was constructed from iron and glass and borrowed on technologies form the ship building industry as well as innovating heating and ventilation techniques that helped to progress climate control technologies. Glass houses served as a parallel to British museums such as the South Kensington museum by collecting, controlling and displaying plants from British colonies in much the same way museums took and displayed cultural objects. Climate control technologies were conceived and innovated on in buildings such as the Palm House. These technologies served as a starting place for climate control in tropical colonies where this technology was used to further colonial and imperial power and control. The building technologies developed in the age of iron and glass buildings helped form building types such as market halls and arcades which urged a shift into a commercialized culture. The Palm House at Kew Gardens stand at the centre of a time where engineering, design and colonialism were closely intertwined and had immeasurable lasting effects on the systems of our world.

15 Mayine L. Yu, “Frame and infill construction,” in Skins, Envelopes, and Enclosures: Concepts for Designing Building Exteriors (London: Routledge, 2013), 120.

16 James Schmiechen, Kenneth Carls, and Professor K. Carls, “Food, Markets, and History,” in The British Market Hall: A Social and Architectural History (New York: Berghahn Books, 1999), ix.

17 “Food, Markets, and History,” ix.

Bibliography

Barringer, Tim, and Tom Flynn. “The South Kensington Museum and the colonial project.” In Colonialism and the Object: Empire, Material Culture and the Museum, 11-27. London: Routledge, 2012.

Desmond, R. G. “Who Designed the Palm House in Kew Gardens?” Kew Bulletin 27, no. 2 (1972), 295-303. doi:10.2307/4109457.

“Richard Turner and the Palm House at Kew Gardens.” In Structural Iron 1750–1850, edited by R.J.M. Sutherland, 78-102. Routledge, 1988.

Schmiechen, James, Kenneth Carls, and Professor K. Carls. “Food, Markets, and History.” In The British Market Hall: A Social and Architectural History. New York: Berghahn Books, 1999.

Valen, D. “On the horticultural origins of Victorian glasshouse culture.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 75, no. 4 (2016), 403-423. doi:10.1525/jsah.2016.75.4.403.

Valen, Dustin. “Imperial Atmospheres: Race and Climate Control on the Niger.” ABE Journal, no. 17 (2020). doi:10.4000/abe.8106.

Yu, Mayine L. “Frame and infill construction.” In Skins, Envelopes, and Enclosures: Concepts for Designing Building Exteriors, 115-155. London: Routledge, 2013.

Images

figure 1: Top: Plan of Temperate House. Bottom: Plan of Palm House. Kew Gardens. 1860. Kew Images. https://images.kew.org/history/maps-plans/plan-palm-house-1860-18934675.html

figure 2: Section of the Palm House, Kew Gardens. Desmond, R. G. “Who Designed the Palm House in Kew Gardens?” Kew Bulletin 27, no. 2 (1972), 295-303. doi:10.2307/4109457.

figure 3: The Great Conservatory, Chatsworth. Desmond, R. G. “Who Designed the Palm House in Kew Gardens?” Kew Bulletin 27, no. 2 (1972), 295-303. doi:10.2307/4109457.

figure 4: Plan, elevation and section by Decimus Burton of the Palm House, Kew Gardens. Kew Gardens. https://twitter.com/kewgardens/status/1200037179604557826/photo/1

figure 5: Proposed cast iron rib as per specifications and working drawings (April 1844), and the wrought iron rib as adopted for the Palm House (June 1845). “Richard Turner and the Palm House at Kew Gardens.” In Structural Iron 1750–1850, edited by R.J.M. Sutherland, 78-102. Routledge, 1988.