The expansion of colonies overseas and the growth of the colonial culture continued to shape the ego of Parisiens and the metropole of Paris to be a world centre and a global nexus in 1900[1]. As the last in the five most important[2] World’s Fairs held in Paris, the Paris exposition of 1900 presented a ‘picture of the world at the close of the nineteenth century with a minuteness and vividness never approached before’. It also featured an unprecedented scale compared to the previous one in the urban space of Paris[3]. The exposition was divided into sections apart from one another and pavilions were distributed along the banks of the Seine[4]. This has contributed a practical reason to the innovation of the double system of the electric railway and the adjacent elevated trottoir roulant[5] that could not only transport visitors across different venues but in the meantime, presented a kind of urban travel and pedestrian experience powered by electricity. Although numerous artifacts and goods were on display to amuse the public, mobility and electricity were remained to be the key demonstrations of urban sophistication and modernity[6] during the exhibit. The engineering of trottoir roulant materialized an integration of electricity and mobility in an urban infrastructure that was tight knitted to the existing urban fabric of Paris. The building of a sensorial landscape on the trottoir roulant was based on the scripted motions and the rapidly growing technologies of that time, which inevitably privileged certain groups in variable contexts. The trottoir roulant not only inspired a new mode of pedestrian travel but also implied a compelling spatial control over the humans, the city, technology, and their relations as Paris was progressing towards modernity.[7]

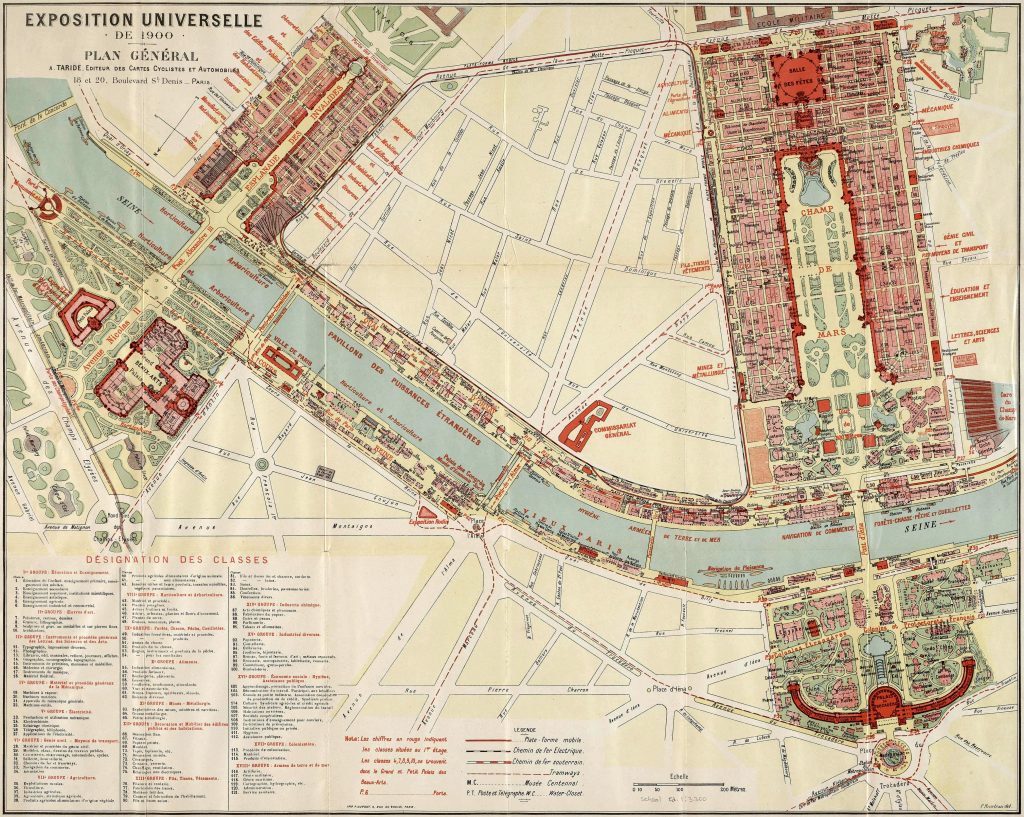

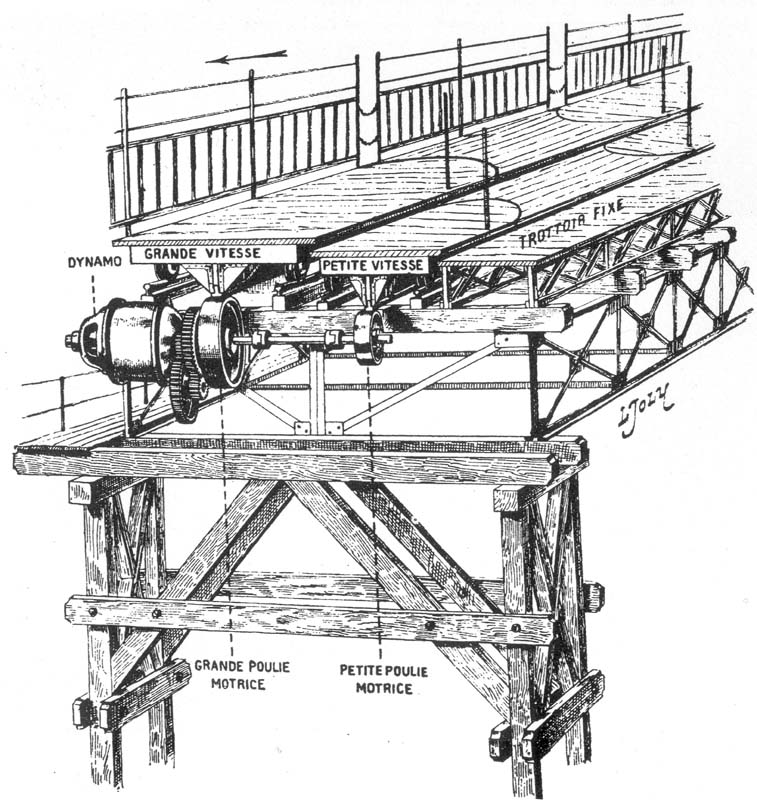

The trottoir roulant was a mobility system proposed by engineer Charles Cavelier de Mocomble (representing the system Blot-Guyenet-de Mocomble) that covered roughly 3300 meters on top of an elevated viaduct at the even height of 7 meters[8]. It was consisted of three parallel platforms: a stationary platform at the outer loop and two movable ones, one at the speed of 1 metre per second and the other one doubled that[9] and was supported by a purposely built independent power station[10]. From the general plan of the exposition[11], the trottoir roulant formed into a complete circuit in the shape of an irregular quadrilateral above Quai d’Orsay along the Seine in the north, Rue Fabert along Esplanade des Invalides, the home of Art applied to Industristies in the east, Avenue de la Motte-Picquet in the south and Avenue de la Bourdonnais in the west next to the main exhibition area of Champ-de-Mars where departments of machineries, electric devices, agriculture, food, etc were exhibited.[12] The trottoir roulant was able to thread the fragmented venues on the south bank of the aforementioned sectors into a cohesive whole[13]. However, it is obvious that the Colonial Exhibits of exotic artifacts and remote races[14] at Trocadéro was not included in the route of trottoir roulant from the plan and nor was it close to the underground railway. Visitors heading to the Colonial Exhibits at Trocadéro would have to cross the bridges on foot, walking aside from the main the highlights of 1900 World’s Fair that could be reached almost effortless from the trottoir roulant. This spatial separation epitomized the aspiration of the World’s Fair of ‘drawing the attention of the entire civilized world to a particular point, at a particular time’[15]. The intricate transportation network lying on only one side of the Seine was a strong indication of visitors’ attention and thus alluding to ‘the civilized world’.

The central position of the trottoir roulant at the 1900 World’s Fair, its fundamental role in jointing the fragments of the exhibits and its careful layout of electric power and mechanics[16] as well as its distancing from the Colonial Exhibits was no accidents but with clear intention to accentuate the centrifugal forces of the exposition[17]. The mastery of technology would enable the possession of power and control, and the manipulation of civilizations.

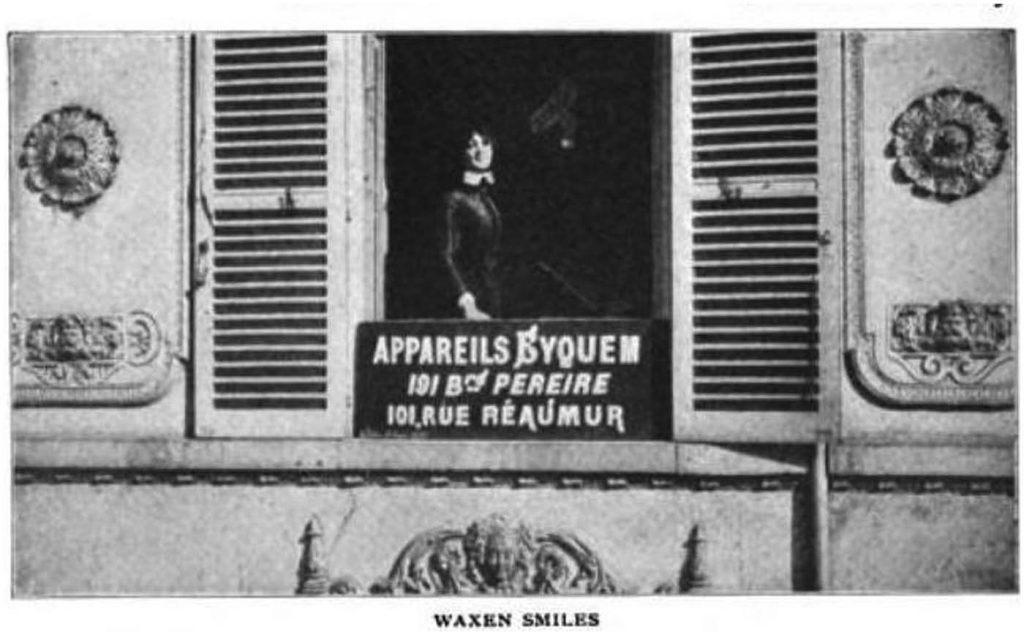

Surrounded by the trottoir roulant, the city blocks of boulevards, retails and residential buildings between Esplanade des Invides and Champ-de-Mars became part of the exhibition[18]. With the viaduct and the trottoir ranlout lifted above the ground, passengers were able to view the city of Paris as a panoramic visual spectacle[19], where the vibrant life of Parisiens was vividly reflected in each ’scene’. As Paris enjoying the fame as ‘a centre for great exhibition’[20] and as each successive exhibition growing bigger and bigger, and making advantage of the urban infrastructures to spatially connect the exhibit venues, the city and the exposition were getting increasingly interrelated[21]. One day the city itself would be the exposition.[22] The trottoir roulant ran in front of many apartment windows, through which passengers heading to the destinations could get a glimpse of the interior life of the apartments[23]. The adjacency of the urban view was further enhanced by the mere movable platforms without the partition of walls and framing of windows.[24] The trottoir roulant was built as a spectacle delivering the reforming power of electricity on people’s daily lives. Its aerial disposition[25] and the designated trajectory privileged an animate viewing platform that almost resembled a surveillance vehicle carrying spectators patrolling the city and observing from above. The visual pressure coming from the trottoir roulant also changed the spatial relation of ‘the second story windows’ to the city. This is particularly addressed in Burton Holmes’s ride on the trottoir roulant where he passed an attractive woman waving her hand in a window and only found out that it was a life-size wax figure with an artificial moving hand[26] to advertise for Maurice Eyquem[27].

The sensorial experience riding on the trottoir roulant largely derived from the travel in motions. An observer reported that the travelling ‘through time and space and simultaneously gazing at all the other passengers passing by – as if encountering a representative sample of humankind: Aha, those colorful appearances who pass by on the runway are not just visitors to the exposition – no, they symbolize the whole of humanity as it passes through time – brr, brr, brr – it almost seems to purr and buzz continuously, and so it goes on and on and on…’[28] The trottoir roulant separated the effortless movement and the spatial-temporal travelling manner above ground from that of the pedestrians below. This impression was described in The Moving Pavement of Butler ‘Endless crowds of people were seen being swiftly carried along, a few who were walking had the effect of skaters rapidly and easily skimming past the rest. All seemed to be travelling in a manner which the tired pedestrian looked upon with envy.’[29]

Through the construction of spatial separation in both the horizontal and vertical planes, the trottoir roulant successfully became an exhibit wonder of the 1900 World’s Fair and continued to appeal the Parisiens in various media publications.[30] The spatial segregation created a provoking narrative echoing the divisions of the civilized and the colonized in the late nineteenth century. As an engineering marvel, the trottoir roulant won the publicity but it also asked for our thinking on how technologies lived in our daily lives and how the strict planning behind would not allow any defiance.

[1] Alexander C.T. Geppert, “Chapter 3 Paris 1900: The Exposition Universelle as a Century’s Protean Synthesis,” in Fleeting Cities: Imperial Expositions in Fin-De-siècle Europe (Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 66.

[2] Geppert, “Fleeting Cities”, 62.

[3] Geppert, “Fleeting Cities”, 74 & 79.

[4] Erkki Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking at the Fair: About Mobile Visualities at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900,” Journal of Visual Culture 12, no. 1 (2013): pp. 61-88, https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412912470523, 67.

[5] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 68.

[6] Geppert, “Fleeting Cities”, 83.

[7] Peter S. Soppelsa (2009), 8.

[8] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 67 & 69.

[9] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 69 & Geppert, “Fleeting Cities”, 79.

[10] La Plate-Forme Mobile Et Le Chemin De Fer Électrique / Program Hebdomadaire De l Exposition (Paris Édition du Figaro “, 1900), 9.

[11] Fig. 1

[12] Geppert, “Fleeting Cities”, 79 & B. D. Woodward, “The Exposition of 1900,” The North American Review 170, no. 521 (April 1, 1900): pp. 472-479, 473.

[13] Geppert, “Fleeting Cities”, 74.

[14] Woodward, “The Exposition of 1900”, 473 & 478.

[15] Geppert, “Fleeting Cities”, 65.

[16] Fig. 2

[17] Geppert, “Fleeting Cities”, 65.

[18] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 67.

[19] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 73.

[20] Geppert, “Fleeting Cities”, 62.

[21] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 73. Gaston Bergeret, Journal d’un nègre à l’exposition de 1900 (1901), 5.

[22] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 73.

[23] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 73.

[24] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 73.

[25] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 73.

[26] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 73-74.

[27] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 86. Notes: “Maurice Eyquem was a well-known mechanical engineer and hardware manufacturer, whose premises were on the Boulevard Pereire.”

[28] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 82. Böttcher, Weltausstellungs-Glossen, 16; see also M. S., ‘The Paris Fair as an American Sees It’, New York Times (19 August 1900), 18.

[29] Geppert, “Fleeting Cities”, 79. Ibid.; Butler, ‘The Moving Pavement’, 276.

[30] Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking”, 71-72.

Bibliography

Fullerton, John, and Jan Olsson. “Trottoir Roulant: the Cinema and New Mobilities of Spectatorship.” Essay. In Allegories of Communication: Intermedial Concerns from Cinema to the Digital, 264–68. Eastleigh: John Libbey, 2004.

Huhtamo, Erkki. “(Un)Walking at the Fair: About Mobile Visualities at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900.” Journal of Visual Culture 12, no. 1 (2013): 61–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412912470523.

La Plate-Forme Mobile Et Le Chemin De Fer Électrique / Program Hebdomadaire De l Exposition. Paris Édition du Figaro “, 1900.

Soppelsa, Peter S. “The Fragility of Modernity: Infrastructure and Everyday Life in Paris, 1870–1914,” 2009.

T., Geppert Alexander C. “Chapter 3 Paris 1900: The Exposition Universelle as a Century’s Protean Synthesis.” Essay. In Fleeting Cities: Imperial Expositions in Fin-De-siècle Europe. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Woodward, B. D. “The Exposition of 1900.” The North American Review 170, no. 521 (April 1, 1900): 472–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/25104981?refreqid=search-gateway.

Vue Prise d’Une Plate-Forme Mobile, III. Catalogue Lumière , 1900. https://catalogue-lumiere.com/plate-forme-mobile-iii/.

Images

Captions:

Figure 1. Genergal Plan of the 1900 Paris World’s Fair. The trottoir roulant lies between Esplanade des Invalides and Champ-de-Mars.

Figure 2. Mechanism of the trottoir roulant.

Figure 3. The “waxen smiles” from Burton Holmes.

Figure 4. The novel and peculiar experience of travelling between branches.

Sources:

Cover image

Étiquettes. March 21, 2013. https://lecomptoirdetitam.wordpress.com/2013/08/21/rue-de-lavenir-paris/.

Figure 1.

Bineteau, P. Exposition Universelle De 1900 : Plan Général. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, November 16, 2013. http://imagebase.ubvu.vu.nl/getobj.php?ppn=330026089.

Figure 2.

Joly, L. Mécanisme Du Trottoir Roulant De L’Exposition Universelle De 1900. March 11, 2011. https://www.worldfairs.info/forum/viewtopic.php?f=10&t=125.

Figure 3.

Erkki Huhtamo, “(Un)Walking at the Fair: About Mobile Visualities at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1900,” Journal of Visual Culture 12, no. 1 (2013): pp. 61-88, https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412912470523, 74.

Figure 4.

ANOTHER VIEW OF THE MOBILE SIDEWALK . August 13, 2013. https://paleofuture.gizmodo.com/rare-photos-of-pariss-mechanical-moving-sidewalks-from-1123349748.