Introduction

Perched on the North peninsula of Halifax, Nova Scotia is a replica of a vintage church, sitting in solitude, overlooking the bay. The park is deceptively serene, and betrays the violent reality of the landscape’s history. A century before, the site was not a park, but a thriving black community named Africville. Africville, established by previously enslaved black families in 1848, boasted quaint houses, a hockey league, and perhaps most importantly, the beloved Seaview African United Baptist Church1. It has been said that the first settlers were initially drawn to the area as it sat above the Bedford Basin, a beautiful bay perfect for baptisms. Shortly after settling, the residents built the church in 1849, and it became the heart and soul of Africville over the next century2. Unfortunately, as the church thrived, its surrounding community lay victim to a government that strategically withheld and implemented certain infrastructures in order to stigmatize, punish, and dominate Africville’s black residents. These racist actions ultimately came to a head in the 1960s when, after years of degrading the landscape, the government labelled Africville as an industrial site and demolished the buildings. Unfortunately, the church was destroyed on a night in 1967 without any proper permission 3. The church that now stands in the same place is a replica built in 2011, a simple structure left to represent a razed community and its culture. However, in the pinnacle of the original church’s life, it represented much more. This essay will explore how the Seaview African United Baptist Church symbolizes Africville’s resistance to institutionally imposed hardships in terms of its role in the community, its position in Africville, and its context in history.

- Clairmont, Donald H. The Spirit of Africville. Halifax, N.S.: Formac Pub., 2010.

- Halifax Regional Municipality. “Africville Map Series.” arcgis.com, 2015. https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=8821561a4f2c44689bc02b172241883c.

- Clairmont, Donald H, and Magill, W Dennis. Africville: the Life and Death of a Canadian Black Community. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 1999.

The Church’s Role in the Africville Community

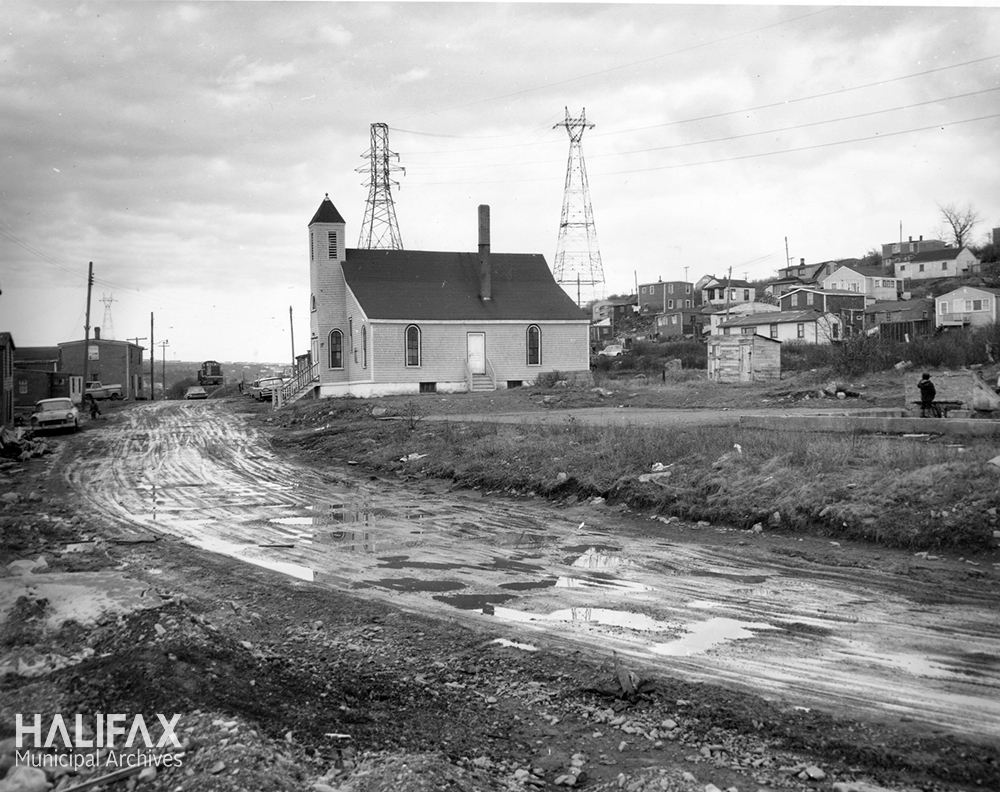

The image above, taken of Africville’s Seaview United Baptist Church in the 1960s, captures the church in all its glory, despite the intrusive infrastructure and ramshackle buildings surrounding the subject. However, at the heart of this systematically-impoverished town, without financial or structural means to even maintain the homes, sat the church, a relatively pristine building of simple architecture. The church featured a classic red gabled roof with a cream exterior and white trim. A variety of window styles were placed at different heights, and wooden stairs led up to the double front door. Details such as a rectangular bell tower, arched windows, and overall larger size differentiated the otherwise modest building from its neighbors and identified the structure as one designed to attract and accommodate a gathering of people for worship. While humble and perhaps even homely to some, Africville’s residents described the building as one that “gleam[ed] in the sun” 4. Indeed, the architecture was straightforward, but the town’s attentiveness and attachment to the church imbued it with additional layers of charm: it was physically preserved and emotionally prized. Religion was of central significance for the majority of Africville’s residents, and through the creation of the church, a collective sentiment of shared values and interests forged a bond in the community. As an apex of the community, the church was not only a place of worship; it was the site for community activities such as youth organizations, clubs, ladies’ auxiliaries, missionary societies, even school classes 5. The church provided an ungoverned, untouched space and fostered a collective identity in a systematically deprived town. While architecturally plain, the residents instilled it with meaning. They made it come alive, quite literally. Upon approaching the building, Africville residents reported a sensorial second architecture of space that was tangible before even inside: in those days, the building pulsed and shook with music and dance as churchgoers worshipped 6. It (was) beat and pounded; it was the heart that pulsed and pumped power and resilience into Africville. The church was more than a physical building, it was a space of pride for collective activity, with its noise, spirit and vibrations reverberating beyond the walls and into the community.

4. Clairmont, 16

5. Clairmont and Magill, 72

6. Clairmont, 17

The Church’s Value Amid a Geography of Disenfranchisement

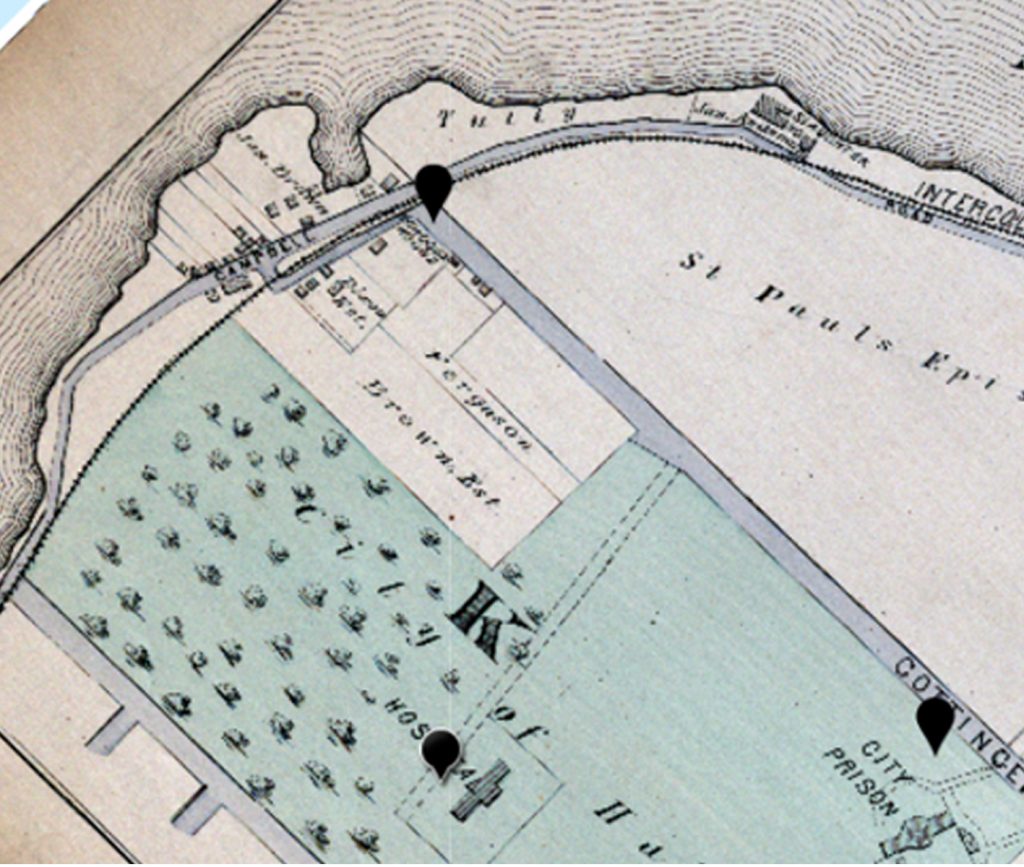

As described above, the Seaview African United Baptist Church was fundamental to weaving a sense of community in the fabric of Africville. Revered and preserved by residents, it additionally stood as a gleaming juxtaposition of hope amid a geography of disenfranchisement. The image above illustrates the extended context of the church, placing the comparatively immaculate building in its landscape of deteriorating infrastructure and decaying buildings. This state of destitution was not reflective of Africville’s residents, but was a direct effect of outright racist maltreatment in a society that viewed black people and the space they occupied as inferior. Despite paying taxes, most necessary services were withheld by the government in a blatant act of racism and attempt to subjugate the community. There was no proper sewage, access to clean water, garbage disposal program or maintenance of the public infrastructure 7. As a result, Africville became a landscape of deterioration and disadvantage, strategically designed by the discriminating government. To exacerbate this issue, Halifax constructed all of its necessary but undesirable developments in the Africville community. In 1853, the Nova Scotia Railway Company cut tracks through the Bedford Basin, ripping through homes and subjecting residents to constant interruption by the deafening train8,9. Incidentally, when passing directly by the church, the train’s rumble finally found a competitor with the church’s passionate worship. Additionally, in 1858, the City relocated their sewage pits to the edge of Africville, and in the next 20 years, they would continue on to build Rockhead Prison, slaughterhouses and an Infectious Disease Hospital. Buildings such as these were relegated to Africville due to worry and complaints from Haligonians about the proximity to their homes, a concern not extended to Africville out of superiority9. By compounding the undesirable constructions on the poorly funded geography of Africville, the City was able to construct the narrative that Africville was dirty and dangerous, and even the beloved Seaview African United Baptist Church was simply that “little brown church”10. However, to Africville’s residents, the church was everything and more. As the incremental addition of undesirable infrastructure inched Africville ever closer to the label of ‘industrial zone’, the church stood as a symbol of hope and resilience as a true representation of Africville’s own culture and pride. Moreover, the church provided a charming space for residents to take ownership over. It was said that even for those who did not attend the church or use its services, it was still described as “our church”, whereas the dump was never something that was theirs, simply something they were allotted, and association with which they fought 11. Suffice it to say, emphasized by an imposed landscape of subjugated undesirability, Africville’s church was a beacon of comparative beauty, pride, and value.

7. Matthew McRae. “The Story of Africville.” CMHR. Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://humanrights.ca/story/the-story-of-africville.

8. Clairmont, 10

9. Halifax Regional Municipality. “Africville Map Series.” arcgis.com, 2015. https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=8821561a4f2c44689bc02b172241883c.

10. Clairmont and Magill, 73

11. Clairmont, 17

The Black Church’s Resistance Throughout History

In addition to the church’s unmatched role and contrasted with the significance in Africville, the Seaview African United Baptist Church represented a symbol of resistance at the historical scale. Much like Africville, the cultural significance of Catholicism in the black community is deeply rooted in the North American slave trade. As is still the case today in larger populations, the majority of the black residents in Africville identified as Baptists12. Baptism as a formal religion became popular in England in the early 1600s, and its emergence in African American populations occurred somewhat simultaneously13. Enslaved peoples were introduced and attracted to the evangelical religion of their masters, as it featured a god that viewed all of His followers, even slaves, as equals under Him. However, slave masters insisted their inferiors attend white churches, in order to control independent, “false” worship and avoid rebellion 14. Nevertheless, as an act of rebellion, slaves found ways to secretly organize gatherings to celebrate their faith, incorporating singing and dancing to create what was called “Negro spirituals” 15. These meetings, hidden acts of rebellion against the system, were dubbed hush harbours, and were organized with secret signals and passwords in order to retain independence. They were not oppositions of physical violence, but the mere act of establishing a separate form of worship to express hope for the future was a strong resistance against the slave masters. Following freedom, churches were not only places of spirituality for previously enslaved peoples, but organizing elements that contributed to the creation of new lives as “citizens rather than property.” 14 As explained by Clairmont and Magill, for blossoming geographies of black culture like Africville, “[t]he establishment of churches and schools in the segregated black communities laid the basis for possible growth of a genuine black Nova Scotian subculture.” 16 Not only do baptist churches help a community grow, but they also allow independence. Each local baptist church is autonomous, meaning there is no governing body that decides the methods of worship, leadership, or financial decisions. In a community uncontrollably on the path to complete decimation at the hands of a racist government, a church that has no human authority, as Jesus is the Lord of the church, is an integral and essential space of freedom 17. In sum, the Seaview African United Baptist Church stands in defiance of the government through the context of history, as historically, black churches represent resistance against the restriction of free thought, and in all relevant eras, they provide a safe space to spur individual and social change.

12. Lincoln, Eric, and Mamiya, Lawrence. The Black Church in the African American Experience. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.

13. Lincoln and Mamiya, 21

14. Maffly-Kipp, Laurie F. “The Church in the Southern Black Community.” Documenting the American South, May 2001. https://wayback.archive-it.org/3828/20141028162837/http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/intro.html.

15. Cox, Tony. “Why Did African Slaves Adopt the Bible?” NPR. NPR, January 24, 2007. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6997059.

16. Clairmont and Magill, 29

17. “Baptists Believe in Church Autonomy.” Baptist Distinctives, January 20, 2015. https://www.baptistdistinctives.org/resources/articles/church-autonomy/.

Conclusion

Africville was a community that had its fate successfully predetermined by a government intent on exploiting the black community for their own benefit. However, the cultural impact of the Seaview African United Baptist Church was a victory unforeseen and lived apart from the government’s control. Even amid the abandoned infrastructure, unwelcome developments, and deep systematic wounds inflicted by a racist society, the sense of pride, collective values, and unity in religion that the church represented cemented the humble building as the heart of a loving community. It may not exist today in its original form, but its impact and symbolism as a site of resistance endures in the memory of anyone who knows the story of Africville.

_____________________________________________________

Bibliography

“Baptists Believe in Church Autonomy.” Baptist Distinctives, January 20, 2015. https://www.baptistdistinctives.org/resources/articles/church-autonomy/.

Clairmont, Donald H. The Spirit of Africville. Halifax, N.S.: Formac Pub., 2010.

Cox, Tony. “Why Did African Slaves Adopt the Bible?” NPR. NPR, January 24, 2007. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6997059.

Halifax Regional Municipality. “Africville Map Series.” arcgis.com, 2015. https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=8821561a4f2c44689bc02b172241883c.

J., Clairmont Donald H, and Dennis W. Magill. Africville: the Life and Death of a Canadian Black Community. Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press, 1999.

Lincoln, Charles Eric, and Lawrence H. Mamiya. The Black Church in the African American Experience. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.

Maffly-Kipp, Laurie F. “The Church in the Southern Black Community.” Documenting the American South, May 2001. https://wayback.archive-it.org/3828/20141028162837/http://docsouth.unc.edu/church/intro.html.

Matthew McRae. “The Story of Africville.” CMHR. Canadian Museum for Human Rights. Accessed February 16, 2021. https://humanrights.ca/story/the-story-of-africville.

_____________________________________________________

Images

Figure 1. Brooks, Bob. Boys crossing railroad tracks towards Seaview African United Baptist Church, Africville, Nova Scotia Archives 1989-468 vol. 16 / negative sheet 5 image 36. Accessed Feb 16, 2021 from https://archives.novascotia.ca/africville/archives/?ID=9

Figure 2. Seaview United Baptist Church, 196? (cropped from original). 102-16N-065.F. Accessed Feb 16, 2021 from https://www.halifaxpubliclibraries.ca/blogs/post/halifax-municipal-archives-remembering-africville-source-guide/

Figure 3. Map of Halifax, 1878, Nova Scotia Archives. Accessed Feb 16, 2021 from https://www.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=8821561a4f2c44689bc02b172241883c