This post is authored with Koyah Morgan-Banke and Jocelyn Mushumanski, second year science students.

Celeste:

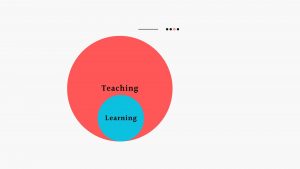

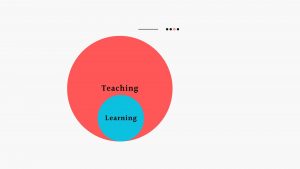

Traditional ways of thinking about teaching and learning can be visualized by imagining learning as some subset of what is taught. These overlapping circles of teaching and learning can be dynamic, changing size as learning expands or shrinks.

Traditional assessments then, can be thought of as pulling a thread (or 3 or 5,000) out of the tapestry of what is taught and framing this thread as a problem for students to solve in some sort of timed setting. If the student is careful or lucky, this collection of threads representing what was taught also represents what they learned in these overlapping dynamic circles.

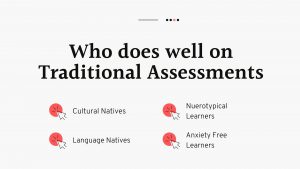

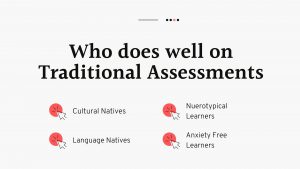

We know that traditional assessments work best for a certain subset of learners, which means they do not work well for many others. (The Racist Beginnings of Standardized Testing is a good place to start if you’re curious about this.)

But here’s an interesting thought. As teachers, most of us have experienced a time when a student learned something in class. And then a while later, maybe the next class, the student comes and says, “That thing I learned was so interesting! I investigated and found out X, Y, Z…” and we think to ourselves, now THAT is real learning.

We can now imagine a shift with learning inspired by, but not encompassed by our teaching.

And that real learning is not ours to own or control. It is fully the product of the student, but should be honoured and celebrated… and assessed as part of the learning arc. Our students bring loads of knowledge with them and learn loads more on the way. This knowledge is more than a passing tangent – it is essential contribution to our understanding of ourselves and our world. Inviting students into the academy in this way truly respects their belonging in this institution – But how do we assess this learning that we don’t own?

In my recent courses, I’ve used an approach that loosely encompasses 3 -steps:

1) Tell me What you Learned! This open ended project format works best when there are fewer constraints and more creativity options for the student. This must allow students to share what they bring and what they learned along the way.

2) Justify a Mark. As learners, I truly trust that students are best able to assess their own learning. (I use ungrading – see Ungrading, edited by Susan Blum).

3) Select the Weighting for this Work. Most recently, I have incorporated Jayme Dyer’s Multiple Grading Schemes, with a lot of personal modifications (see below)

This past term, I developed a Tree Project. In a nutshell, students picked a tree and watched it throughout the term, tying in what they witnessed and investigated to our course material. This project could be done in teams or solo, and could count for 10% or 25%, if a student chose to do the project. (It was also an option to not do the project and to simply count exams instead.) For projects worth 25%, this project was framed as an alternate way to demonstrate understanding of course material and students were given this guidance:

“**The default will be 10% of your course grade. Some learners learn best with project based assessments. If you would rather put substantially more effort into this project, you can choose to count this project for 25% of your grade, with justification. Your exams will count for less in this scenario, but will still be weighted equivalently.

For a project worth 25% of your course grade, you should demonstrate that you understand every major concept, or nearly every major concept. For example, your genetics should cover: ploidy and chromosome number, a demonstration of cell division with crossover, a Mendelian genetics problem (a hypothetical trait is fine), a pedigree“

Koyah:

“Often when courses provide a marking rubric, the expectations are clearly outlined, and your execution of those standards depends solely on whether or not you included that content. Because the guidelines of this project weren’t heavily structured, there was a lot of room to experiment with new ideas- it motivated me to think outside the box and determine what “exceeding expectations” would mean to me. There was no direction from anyone telling me what I would need to do in order to succeed, and because I didn’t know that standard, I was more inclined to push the limit of this project.

I don’t think that there is enough opportunity for first-year science students to be creative, and as someone who often tries to bridge the gap between science and art, I saw this project as a challenge and a chance to try something different. One of the parts of this project type I particularly appreciated was the optional weighting – it gives students the opportunity to take big risks without having to worry so much about it not working out to the extent they would have liked it to. This optional weighting style also caters well to different types of learners, as I find myself often suffering from severe exam anxiety. I prefer to have something I can continuously work towards and refine over time, but this isn’t the case for all students, and this project style respects that.”

Jocelyn:

“In all of my other first year university classes at UBC, the rubrics and expectations for projects and assignments were quite specific and detailed. This led my peers and me to usually choose the easiest and fastest way to achieve the allotted points. The Tree Project in Biology 121, however, was designed in a way that was completely unique to me. While working on past projects in high school, I had completed self-evaluations and had the chance to declare a grade that I thought was fair, but the Tree Project gives students complete control over their learning. This project gave my partner and me total freedom to investigate and include any topic that we found interesting or important, allowing us to stray away from only discussing the topics we had been taught in class. We were able to explore the cultural and historical significance of our plant, rather than just relying on a scientific point of view. At first, having complete authority over the contents of our project was daunting. I felt unsure of the quality of my ideas as well as the length and depth of our work. I knew Koyah and I could easily complete a decent project, but achieving an extraordinary grade seemed difficult. Yet, throughout the term, as Koyah and I devoted so much time to this project and consulted many experts and peers, I gained confidence in the content of our project. I was immensely proud of our work as we reached completion and I knew this was the most outstanding project I had ever worked on. While the Tree Project taught me so much about Salal, I also profusely developed my self confidence, and it helped me learn how to rely on my own validation rather than others.”

Celeste:

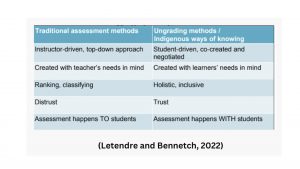

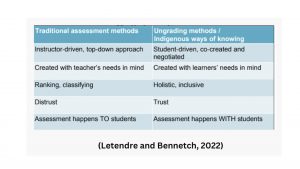

So what does this have to do with decolonization? For several years, I have leaned into a poster (Letendre and Bennetch, 2022) with this small but very impactful table in the upper corner:

At it’s core, decolonzing assessments centres the learner and proceeds with a sense of respect and negotiation.

And then the first project came in and it was beautiful, creative, learner centred, and captured everything I hoped for:

Biology 121 Term Project, The Tree Project, Morgan-Banke and Mushumanski

Koyah:

“I knew instantaneously that I wanted to do my project on salal. My family and I have had many dinner table conversations about the historical importance of the plant and how little it is acknowledged today.

When this project was first announced and I began trying to formulate a plan, I found myself stumped as to how I would get an “amazing” grade. Thinking in numbers proved to be quite harmful to my overall movement through this project. However, as reassured by my professor and the limited project guidelines, I forced myself to let go of the importance of a specific number grade and focus my energy towards creating a project that I myself thought would be both impressive and reflective of what I learned throughout the term. I basically brainwashed myself into thinking that if I do my best, and I mean my very best, then my effort will be represented in my work and provide me with a final mark that is fair. I knew I needed to take a risk in order to make sure this project would be memorable, which is why I decided to create a comic book. I have little to no experience writing comic books, so I was aware of how time consuming and challenging this whole process was bound to become. I was going to need some help, hence why I decided to recruit a trusted friend of mine who was also taking the course with me. I couldn’t find anyone else willing to work with me on such a challenging idea, as many other students I spoke to figured we were biting off more then we can chew – a totally fair assumption! Even if we were biting off more then we could chew, I was dedicated to the success of this project more than any assignment I have completed in my first year of university. This is probably because the alternate assessment encourages students to include elements that the student themselves are passionate about. For me, cultural history was a big interest of mine that I wanted to incorporate into the project. I found inspiration from the double-language-labeled signs around UBC, and from my family, who has worked in language archiving for decades.”

Jocelyn:

“This project gave me a chance to investigate a plant I had never heard of and immerse myself in a culture I had not previously explored. My partner Koyah introduced me to Salal plants and explained their deep significance to coastal indigenous communities, such as her own. While I initially felt more confident discussing the scientific aspects of this plant, I gained extensive knowledge and understanding of the cultural and historical perspectives of Salal. By the time we handed in our project, I knew a great deal about Salal from many different perspectives. The freedom we were given with this project allowed me to better know my friend, the land I live on, and the culture of the indigenous people of that land. ”

Biology 121 Term Project, The Tree Project, Morgan-Banke and Mushumanski

Celeste:

What immediately stood out to me, along with the artistry, was the substantial incorporation of Indigenous knowledge that ran throughout the project. I did explicitly invite students to do this, so I was excited to see this in action and I immediately went to the student’s self-assessment. The following quotes are exerts from the very thoughtful reflection (shared with permission):

“Working on this project has not only allowed me to relate what we are learning in lecture to real-world practices, but it has also encouraged me to reflect on my place in the science community as an indigenous student.”

and later…

“For this comic, I made it a goal of mine to research and include the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ language name and the English assigned name. I used these terms throughout the comic to encourage the memorization and casual use of this name. I then reached out to my grandmother, Chief — of the — Nation, as to gain her thoughts and knowledge on how I can incorporate cultural significance into my project.”

I felt overwhelmed and I phoned a friend, Elisa Baniassad (who leads our Centre for Teaching and Learning Technology). In her perfect Elisa way, she eloquently summarized what I could not articulate in my head:

“You did a thing to remove humiliation and subjugation from your syllabus. And voila — an Indigenous student is able to actually feel seen, and do their work with pride and confidence. You can see that in the product. It is not an apologetic product, where the student is hesitant or fearful. You can feel the sense of fundamental belonging in the entire artifact”

And that was it. By offering unrestricted significant options for students to demonstrate their learning with pride, we can systematically remove some of the punishment protocols that are embedded in our processes. We further UBC’s stragic plan, which commits to “support(ing) Indigenous students to achieve success, however they choose to define

it.” (Note that our strategic plan carefully passes the definition of success to the learner.)

Several students in this class submitted projects highlighting trees from their home countries or regions, reinforcing their feeling of belonging, emphasizing that their prior knowledge matters, and inviting a sharing of knowledge with a spirit of humility. By doing so, we are able to centre ourselves as learners of the knowledge systems that our students bring to us.

“We have inherited and benefited from our current systems of harm”

–Will Valley, West Coast Teaching Excellence Award recipient, 2024

I am confident that we can do better by acknowledging the harm we continue to do, and working with our learners towards a practice of humility with our assessment work.

Biology 121 Term Project, The Tree Project, Morgan-Banke and Mushumanski

Koyah:

“Both my partner and I agree that the final project we submitted was the best assignment we have submitted in our entire academic careers. No aspect of creating this project came easy per say, but it is definitely easier to stay motivated when you are encouraged to include aspects of yourself that you are passionate about . This project gave me the opportunity to discover more about the rich history of salal plants as a staple food for many indigenous communities. This prompted me to work outside the classroom and connect with my family in Macoah, BC. However, it was also important to me to research and include the history of the indigenous communities whose land my partner and I were able to create the comic on, and whose land all UBC activities take place on. Hence, we used both the English and Musqueam interchangeably to encourage language learning during the read and provided a land acknowledgement within our comic.

Taking part in the creation of this project has influenced the way I will approach future projects at UBC, as I have learned a great deal about my strengths and interests through the completion of this alternative assessment. This project has offered me a safe place to take risks and improve my overall confidence. I look forward to taking more risks like this in future assignments and will continue to try and work outside of the box.”

Reference:

Letendre, Angela and Bennetch, Rebekah J. (2022). “‘A new-old way of doing assessment: Indigenous ways of knowing and Ungrading in a pandemic” Poster at the Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. https://www.stlhe.ca/conferences/2022-stlhe-annual-conference/