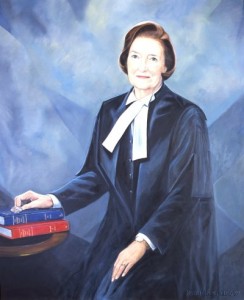

W. Anita Braha

by Susan Boyd and Camille Israel

W. Anita Braha gave an inspiring talk titled “A Feminist Practice: A Chronicle of Issues Over the Years” about her experiences as a feminist and a human rights lawyer. Her stories showed us that her work on feminist projects as a student gave her experience and contacts that paid off in future opportunities.

Law was not Anita’s first career choice – she told us she used to want to be a comedian, and certainly her sense of humour was evident in her talk. Once she settled on law, though, her clear goal was to be a human rights lawyer. She went to graduate school to pursue a Master’s in Political Science at the University of Toronto, where she was part of a coalition of students and administrators who, after a long struggle, got the university to pass one of the first sexual harassment policies in Canada. Anita then studied law at Osgoode Hall Law School, which in the 1980s could be a hard and hostile environment for feminists and lesbians. While there, she was active in the

National Association of Women and the Law (NAWL), which had a number of caucuses across Canada. In her third year, she undertook a directed research project on the issue of pay equity, meeting feminists who were working in the field, such as Carole Geller of the PayEquity Coalition, with whom she later worked.

After graduating in 1986, Anita articled with the Official Guardian of Ontario (now the Children’s Lawyer), which provided an interdisciplinary environment due to its focus on child protection and mental health. Her principal was Susan Himel, now a judge on the Ontario Superior Court.

In the late 1980s, Anita moved to Vancouver, where, through her involvement with NAWL, she met a number of feminist lawyers, such as Gwen Brodsky and Shelagh Day, who hired her as a researcher on their important 1989 publication Canadian Charter Equality Rights for Women: One Step Forward or Two Steps Back? She then (re)articled at the BC Public Interest Advocacy Centre, and was offered a position despite the fact that they did not normally hire back articling students.

During this time, she was asked to represent the first complainant under the University of Toronto’s sexual harassment policy, who was an engineering student. At issue was whether leering constituted sexual harassment. The defendant, 60-year old chemical engineering professor Richard Hummel, was accused of following and intensely staring at female swimmers at Hart House Pool. The board held that his actions did constitute sexual harassment. The decision was immediately appealed, and the defense hired Morris Manning, a prominent criminal litigator. As co-counsel, Anita retained Kate Hughes, who later represented LEAF in its intervention in Meoirin v. BCGSE, the landmark gender discrimination case. Anita’s client won the appeal, but the decision was not uncontroversial. Maclean’s columnist Barbara Amiel strongly criticized the case as “the utter debasement of the genuinely serious nature of sexual harassment.”

Anita worked on other groundbreaking cases, including a worker’s compensation case that established Rape Trauma Syndrome (RTS) as a compensable injury. In that case, the victim had been brutally attacked and raped, but had no lasting physical injuries. Anita worked with Vancouver feminist legal consultant Sandra Goundry and an expert witness to show that RTS constituted an injury, and her client received a full disability pension.

Anita started her own

law firm with a colleague in 1992, sharing a library and other resources with another small firm. She eventually ended up taking institutional as well as individual clients, and has, somewhat unusually, worked for unions, employers and individuals. She has done policy work as well as litigation and education. She has also collaborated with other lawyers on many files. She was an appointed adviser to the

City of Vancouver Women’s Task Force.

Anita’s talk contained many nuggets of wisdom. She told students interested in pursuing a feminist/social justice legal career to follow their passion, and that volunteering with people or organizations doing the kind of work that interested them is a great way to make connections, which could turn into paid opportunities down the line–sometimes in unexpected ways! It is important to help other lawyers and activists and they will reciprocate sooner or later. She said that creativity, persistence, preparation and hard work were crucial in her pursuit of the kind of career she wanted. Most of all, she reminded students to stand by their convictions and principles and to draw strength from them. In her experience, people are drawn to those who have strong core principles, including feminist principles. It is important to speak up and to “stand up and be counted” whenever possible. You may be attacked for your convictions, but others will rally around you. Finally, Anita told us that it is important to be respectful of one’s clients and that she had learned a tremendous amount from her own clients about strength and grace in the face of hardship.

This piece is an excerpt from an article that first appeared in LawFemme Volume 10, Issue 2.