Pow Wow and the Power of Imagination

Fuck 2016

Asking ‘What If’

“Its amazing how those ideas spoken back in the present have become the future.”

– The Henceforward

Indigenous Futurism (IF) is the re-imagining of Indigenous bodies, identities and spaces in the past, present and future. IF is imagining the what if. It creates an alternative vision to the realities of colonialism that serves to inspire resurgence and resistance. But it goes well beyond inspiration too: IF has the capacity to change the future by imagining it differently. Imagine Otherwise as Daniel Heath Justice might say.

In Plato’s Republic he argues against the legitimacy and importance of poets and theatre. He distinguished between praxis or ‘real life’ and fictio or ‘make-believe’ and says that anyone who reacts emotionally to something that is not real life is not in their right mind. Clearly Plato has never seen an episode of Criminal Minds.

Cast of Criminal Minds

Cyberspace is the modern arbiter of identity and it shapes the landscape of imagination. It’s connected to real life – it is real life. Here in cyberspace the lines between praxis and fictio are not as binary as Plato assumed.

Plato Face Palm via Laura Breiling (Tumblr)

IF understands this because Indigenous ways of knowing tend to be less bound up in binaries than Western thought. IF also knows that the lines between imagination and reality are not so easily defined. Imagination has the power to inform reality.

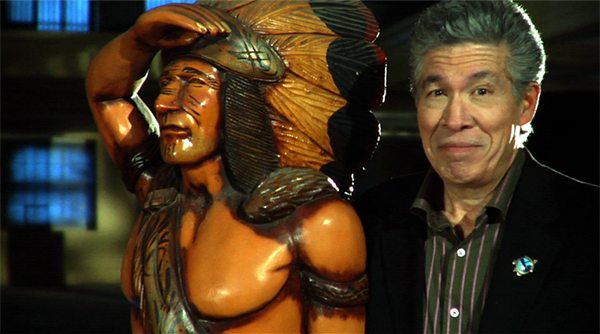

Skawennati Tricia Fragnito clearly understands the power of imagination in IF. She says that the Pow Wow of the Future in Timetraveller™ “was the first time [she] consciously imagined Native people in the future”. Reflecting back on this moment she remembers thinking “there are no Native people in the future… and I think that’s scary. Its possible that if we’re not imagining ourselves in the future we won’t be there.”

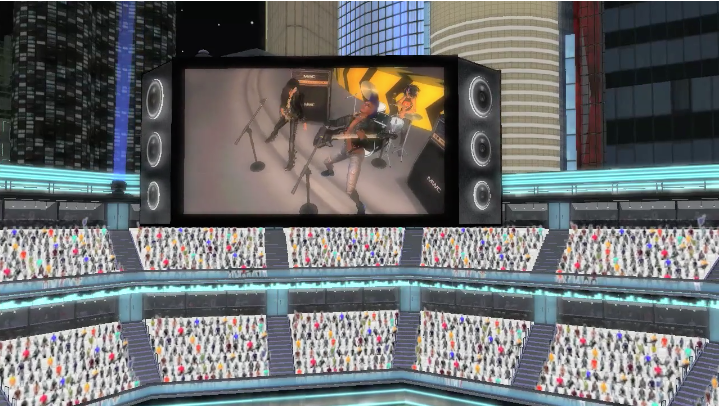

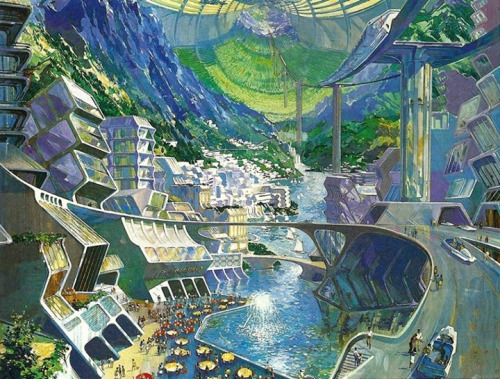

In the Pow Wow of the Future, she boldly imagines a world where Indigenous people are not simply present but they are powerful, self-determined and thriving. When Karahkwenhawi transports to 2112 the scene opens with a packed stadium where a vibrant, global-scale Pow Wow is unfolding.

Pause here: this can’t be overlooked.

There is a stadium filled with Indigenous people freely celebrating their culture and practicing their traditions uninhibited and uninterrupted by settler colonialism. Given the context of a post-contact history bent on wiping out this population and its culture – small pox blankets, potlatch bans, residential schools, wounded knee, the Indian Act, mass incarceration – this is not a docile vision that can be taken for granted. Indigenous existence in the present speaks to their resilience as a people. This imagination of Indigenous people in the future is pure and fiery defiance to the settler-colonial agenda.

TimeTraveller™ Episode 4: Host of the Pow Wow of the Future

Skawennati expands on this defiance, and resilience, through the dialogue of the Pow Wow’s host:

“My grandmother told me, at one time her grandmother told her, the Pow Wow was outlaaaaawed.

*crowd boos*

“They didn’t want us to get together because we’d talk… we’d plan… so what did we do? We got together in private. We got busyyy. As record numbers of Indian babies were born in the 21st century, the Pow Wow grew and thrived with more dancers, singers, and drummers – bigger shows, larger audiences, woooorld wiiiiiide broadcast rights”

*crowd cheers* *view zooms out to show a packed Winnipeg Olympic Stadium*

TimeTraveller™ Episode 4: The FN Punk band “Dead Mohawks” at Pow Wow of the Future.

Another significant component to the way Skawennati has imagined the Pow Wow of the Future is the way that Karahkwenhawi participates in it. She doesn’t just watch – she is in it. It is one thing to present a far away vision of the future. But it is quite another to ask the viewers to participate in it in their present through identification with the protagonist.

Of course, we haven’t completely arrived at Skawennati’s vision of the future in the present yet. That is part of why Skawennati’s use of IF is so powerful. There’s the ‘not yet’ and the already happening are joined yet in tension with one another – with the longing for the ‘not yet’ firmly situated in the present, fully available to participate in until it is realized in full.

TimeTraveller™ Episode 4: Karahkwenhawi participating in a jingle dance competition at Pow Wow of the Future.

“Beauty has the power to be solicitous. It moves us towards different arrangements”.

– Richard Topping

Speaking on the power of imagination to change the future, theologian Richard Topping calls into question modernity’s tendency to laugh at or label as naïve those who imagine a better future. He is critical of those who say, “you’ve got to live in the real world.”

“What modernity lacks is the capacity of imagination. We call something the real world because we just can’t imagine it changed. The ‘real world’ is very often the world that people with the biggest speakers say it is – they can just drown out other voices.”

– Richard Topping

In contrast, he encourages us to be bold in our imagination of the future. Much like Skawennati demonstrates in Timetraveller, Topping argues that imagination is an integral tool in social change towards a more just world.

“The world you imagine you’re living toward has this kind of ethical force to change your behaviour now… ontology shapes ethics.”

– Richard Topping

What Skawennati’s TimeTraveller and Topping’s theology of imagination have in common is that they both ask ‘what if’ in a manner that shifts what is. This activity is at the heart of Indigenous Futurism.

TimeTraveller™ Episode 4: Drumming at Pow Wow of the Future.

Treatment

Now, I know we’re supposed to write a treatment in this blog post for a new episode of Timetraveller. The truth is, I’m struggling with that. I’m struggling to use my imagination. It’s been a strange and difficult week for all of us with the election and I think I unknowingly used up my creative faculty in the last few months imagining a world where the most qualified candidate in recent history could be elected President of the United States regardless of her gender. I spent too much creative energy imagining a world where racism, misogyny, and bigotry wouldn’t succeed, wouldn’t receive accolades.

I may have spent the last ounce of creativity I had on writing this poem.

2016

Fuck 2016.

“You don’t even know.”

Fuck 2016.

I know,

I know.

The second line is a quote from the film Moonlight (WHICH YOU SHOULD ALL SEE – the first paragraph of this review explains the scene this line is taken from). The last lines are from an imagined conversation between Hillary Clinton and Huma Abedin about emails and cheating husbands from a This American Life episode called “Master of Her Domain… Name”. My friend answered the phone with “fuck 2016” to me the other day. So it’s a stretch to say I even wrote this poem.

Still from Barry Jankin’s ‘Moonlight’.

Hillary Clinton and Huma Abedin.

I feel like a bit of a hypocrite, saying we need to re-engage with our imagination but seemingly lacking the capacity myself.

If I were to write a treatment, it would probably have something to do with Indigenous people around the world leading a movement of renewable energy that was consistent with their self-determination and relationship to land. It would somehow manage to lift the world out of the current climate crisis and simultaneously thwart the fossil fuel industry’s tendency to exploit Indigenous land and people for profit.

I believe this can happen. I earnestly do. But even as I type it the cynic in me is crouching in the shadows, leering at any possible impediment to hook onto and drag it down. The policy analyst in me scoffs at the plethora of institutional barriers in the way. The consumer in a neo-liberal capitalist society slyly questions whether I really want that vision to be realized.

I’m part of the problem in that way. I need to forget the ‘real world’ and imagine. I need to ask what if.

Even that’s not entirely accurate though: I can imagine. Sometimes I’m even good at it. But I’ve always been reticent to voice what I see in my imagination. It’s fear. I’m afraid of looking foolish, naïve. I’m afraid of failing. I’m afraid I’ll change my mind about what I want in my imagination. If people knew what I imagined and then it didn’t happen it would be the result of either hypocrisy or failure. I need to get over this. But that’s hard while abruptly coming down from the high of imagining a world “in which women’s inferiority isn’t a given”.

Part of the issue is that when it comes to policy I consider myself a pragmatist. That means that despite acknowledging its abounding flaws, I like to work within the system for gradual change. I believe the work of Justice is slow and sometimes grey. I don’t believe in smashing the patriarchy. I believe in dismantling it, piece by oppressive piece.

I need to learn how to hold imagination and pragmatism in tension. I need to believe that both are at once possible. Maybe I have Plato to blame for the difficulty I have in this. The binary between praxis and fictio has survived the last 2,300 years and wound its way into my Fuck 2016 worldview. I know that there has to be a way to dismantle the patriarchy through pragmatism while simultaneously imagining otherwise.

2 Weeks Later…

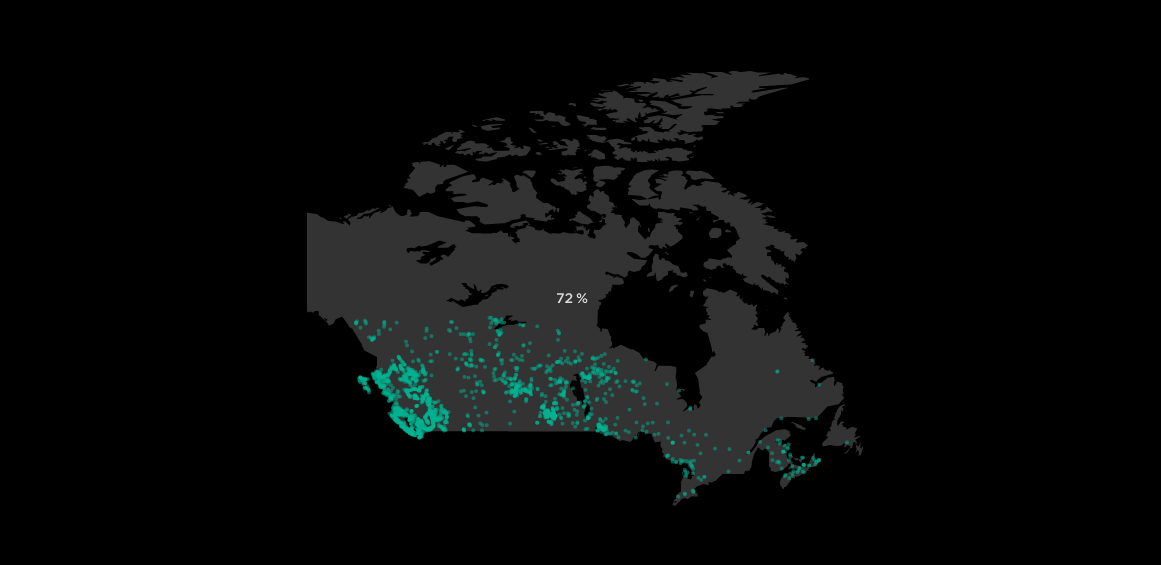

As a white cisgendered woman, I have the privilege to not be able to imagine otherwise sometimes. My survival doesn’t depend on it. But many others do not have the luxury to give up on imagining.

Thankfully, imagining isn’t something we have to do alone. In fact, creativity is bound up with community. When we struggle to imagine, we can rely on the imagination of others. In lieu of creating my own treatment, and in order to re-centre Indigenous voices in this post, I will rely on the strength of Faith Juma’s and Hunter Knight’s imaginations in The Henceforward podcast on Indian and Cowboy.

‘The Henceforward’ podcast cover art.

This series “considers relationships between Indigenous Peoples and Black Peoples on Turtle Island” by “reconsider[ing] the past and reimagin[ing] the future.” Episode #5 “Back to the Henceforward” imagines a city that remembers where it came from; where the #idlenomore and #blacklivesmatter movements have formed the city’s government; where Black and Indigenous histories are not forgotten but built into the very structure of the city. They imagine a city that smells tantalizing after society has been relinquished of its control by fossil fuels; where healthy relationship to the land informs the city’s design; where food is plentiful yet not wasted. They create a world where where empowering cross cultural kinship is the norm not the exception; where the relationship between past, present and future is not linear.

The Henceforward imagines a beautiful and decolonized future. But as it bends space and time it also acknowledges the struggle inherent in the work of imagination.

“We need to pause for a minute and talk about where we’re coming from. Because it turns out that thinking about the future is really hard. But that’s also why it’s necessary. If we’re serious about the work of decolonization then we need to know what we’re working towards.”

– The Henceforward

They explore this world through the TTCdelorean, “a time-space compression device” that is fuelled by hope alone. What I love about this is that the TTCdelorean can run even on even the smallest fumes of hope. When it becomes difficult to imagine the future it means we are running low on the fuel of hope. But we keep going. Because inherent in Indigenous Futurism is hope.

“We need a kind of extreme hope to be able to imagine that future”

– The Henceforward

This is Indigenous Futurism. Thank you Faith Juma and Hunter Knight for continuing to imagine when I was unable. Thank you for extreme hope. Thank you for asking what IF.

___________________________________________________________________

References

Barry Jenkins, Moonlight Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9NJj12tJzqc

Gratitude.

Daniel Heath Justice, Imagine Otherwise: http://imagineotherwise.ca

Gratitude.

Faith Juma and Hunter Knight, The Henceforward “Episode #5: Back to the Henceforward” on Indian and Cowboy: https://www.indianandcowboy.com/episodes/2016/9/6/the-henceforward-episode-5-back-to-the-henceforward

Gratitude.

Lauren Chval, “Moonlight Review: So Good it Hurts”, Red Eye Chicago: http://www.redeyechicago.com/movies/redeye-moonlight-review-so-good-it-hurts-20161027-story.html

Gratitude.

Lindy West, “Her Loss”: New York Times, 2016: What Happened on Election Day: http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/projects/cp/opinion/election-night-2016

Gratitude.

Skawennati Artist Talk, Dunlop Art Gallery, 2016: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sKjjZea_AlE

Gratitude.

Skawennati Tricia Fragnito, Timetraveller™: http://www.timetravellertm.com/index.html

Gratitude.

Richard Topping on Imagining Renewal, 2016: http://www.equipandbuild.org/equip-and-build/2016/9/19/imagining-renewal

Gratitude.

—————>

—————>