HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) and AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) affected nearly 37 million people and killed about 940,000 people worldwide in 2017. HIV is a sexually transmitted virus that can lead to AIDS and a weak immune system susceptible to a variety of smaller illnesses. The virus works by reducing the number of CD4 (T cells) in the body which fight off infections. Currently, there is no effective or widely used cure and HIV/AIDS is treated using antiretroviral therapy, which can prolong infected peoples’ lives. However, there have been some claims of people being “cured” of HIV, but the language used to describe it should be analyzed further.

Two instances of a “cure”?

In 2006, Timothy Brown (often referred to as the “Berlin patient”) was using antiretroviral drugs to treat his HIV when he also developed acute myeloid leukemia, a blood cancer. He chose to undergo a blood-stem-cell transplant and at the same time volunteered for an experimental anti-HIV treatment; his bone marrow was replaced with that of a tissue-matched donor who had two mutated copies of a gene that prevents HIV infection (a Δ32 mutation of the CCR5 gene, which codes for a receptor). Mr Brown was cleared of leukemia and HIV had stopped replicating in his body.

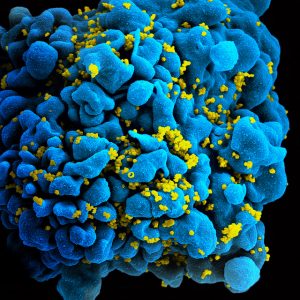

Scanning electromicrograph of an HIV-infected T cell. Creative Commons Credit: NIAID

Another such recent case is being dubbed the “London patient”. Doctors at University College London led by Ravindra Gupta treated a patient living with HIV and Hodgkin’s Lymphoma with a similar stem cell transfusion. The donor also had the protective double Δ32 mutation inherited from both parents. The patient stopped using antiretrovirals 16 months after treatment, and 18 months after stopping the drugs there has been no sign of HIV returning to his body. This second case proved that the first case was not a fluke and that this type of treatment could be widely used.

Issues in news reporting

However, it might not be appropriate to call these definitive “cures”; it would be better to label them as “functional cures”. This is because the virus could still be lying dormant in the body, as it most likely is, and be at a level that is undetectable in the blood. Furthermore, this treatment acts by stopping the reproduction of the virus and not completely removing it from the body. Therefore, it is also acceptable to use the phrase “in remission” when describing the state of the virus. Unfortunately, this issue of science communication using incorrect language can be seen in many articles about this story, such as this article by the New York Times. Obviously this article will attract more attention because of its exciting headline, but it is not good journalism and can lead to misconceptions. In conclusion, news sources should ensure they are using correct language when describing possible major events in science to better inform readers.

HIV/AIDS awareness symbol Creative Commons Flickr

-Sepehr Haghighat