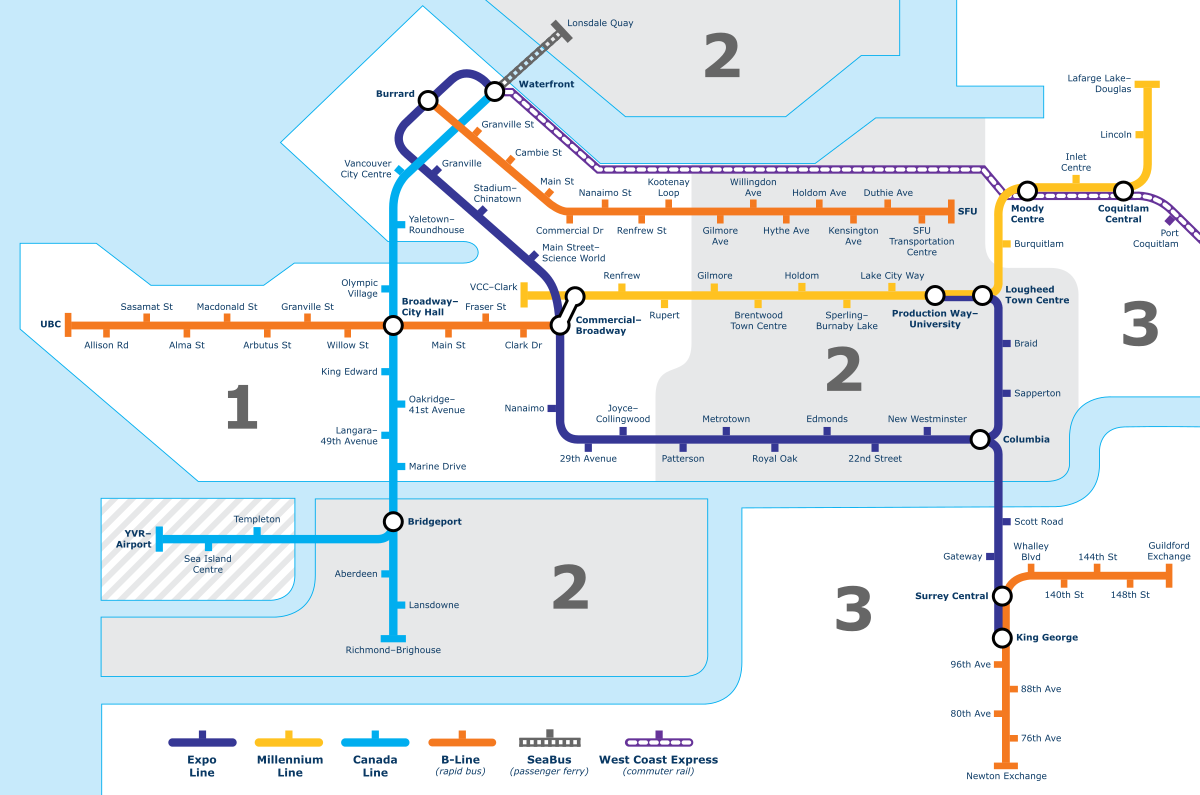

Sustainability is the biggest driver behind transportation planning policies in Metro Vancouver. Some of the guiding documents include: Transportation 2040, Greenest City 2020 Action Plan, Metro Vancouver 2040, and TransLink’s 10 Year Vision. What goals and methodologies do these documents lay out, and how do they really play out in Vancouver’s transportation engineering?

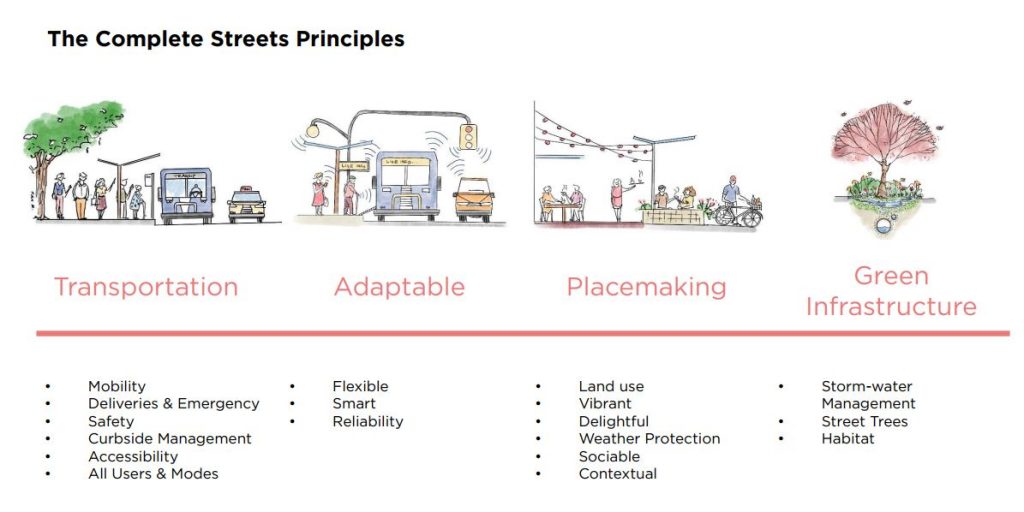

The primary goal of Vancouver’s sustainable transportation policies is to reduce carbon emissions to meet Greenest City 2020’s target of reducing community-based greenhouse gas emissions by 33% from 2007 levels by 2020. Currently, vehicles account for over 30% of greenhouse gas emissions in Vancouver. Transportation-specific targets to meet this goal are to increase the number of trips within the Lower Mainland by active transportation (bike, foot, or transit) to 50% by 2020 and 66% by 2050, and to reduce the average distance driver per resident by 20% from 2007 levels. On top of these, the Complete Streets Policy Framework creates guidelines for designing streets that integrate planning for all modes of travel as well as land use, urban design, green infrastructure, and public space. The Complete Streets Principles are shown below in Figure 1.

In order to meet these goals, the City of Vancouver has primarily looked at promoting active transportation via improving greenways, bikeways, and transit. Some examples of projects currently being undertaken within the scope of the Transportation 2040 Plan include: the Arbutus Greenway, the 10th Avenue Corridor bikeway, the Commercial Drive Compete Street, and the Georgia Gateway West Complete Street.

The result? Although the overall carbon emissions goal is currently projected to fall short of the 2020 target, the transportation targets have met expectations. As of 2016, both of the Greenest City 2020 transportation targets have been met; 50% of trips are currently being taken by active transportation means, and the average distance driven per resident has been reduced by 32% from 2007 levels.

So what’s missing here? The narrow focus of Vancouver’s sustainability policies on reducing greenhouse gas emissions creates a glaring gap in other elements of sustainability, such as road ecology and green infrastructure. This is somewhat mitigated by Vancouver’s Complete Streets initiative, which includes elements of green infrastructure in street level design, but still lacks transparent guidelines and goals for creating green roads. Furthermore, there has been a lack of research on the specific effects of urban road networks on Vancouver’s ecology. Moving forward, it would be great to see Vancouver’s sustainable transportation goals be expanded to include more than just climate change mitigation strategies.

References

City of Vancouver. (2017). Complete Streets Policy Framework.

City of Vancouver. (2012). Transportation 2040.

City of Vancouver. (2017). Greenest City Action Plan. Retrieved from City of Vancouver: http://vancouver.ca/green-vancouver/greenest-city-action-plan.aspx

Government of Canada. (2017, November 3). The Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. Retrieved from Canada.ca: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/pan-canadian-framework.html

Metro Vancouver. (2017). Retrieved from Metro 2040: http://www.metrovancouver.org/metro2040

Province of British Columbia. (2017). Climate Action. Retrieved from Province of British Columbia: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/transportation/transportation-environment/climate-action

TransLink. (2017). 10-Year Vision for Metro Vancouver Transportation. Retrieved from TransLink: https://10yearvision.translink.ca/

Figure 1: Trans Canada Highway Wildlife Overpass in Banff National Park

Figure 1: Trans Canada Highway Wildlife Overpass in Banff National Park