Question:

Question:

- In this lesson I say that our capacity for understanding or making meaningfulness from the first stories is seriously limited for numerous reasons and I briefly offer two reasons why this is so: 1) the social process of the telling is disconnected from the story and this creates obvious problems for ascribing meaningfulness, and 2) the extended time of criminal prohibitions against Indigenous peoples telling stories combined with the act of taking all the children between 5 – 15 away from their families and communities. In Wickwire’s introduction to Living Stories, find a third reason why, according to Robinson, our abilities to make meaning from first stories and encounters is so seriously limited. To be complete, your answer should begin with a brief discussion on the two reasons I present and then proceed to introduce and explain your third reason from Wickwire’s introduction.

There are many reasons why those listening to first stories in 2016 have limited capacity for understanding or making meaningfulness from them. The two reasons that Professor Paterson discusses in English 470A notes include the fact that the social process of the telling of the story is disconnected from the story and the 75 year gap in families and community storytelling as children from 5-15 were removed to non-native residential schools. Professor Wendy Wickwire, in the introduction to Living by Stories: A Journey of Landscape and Memory, further explores our limitations to hear the stories, and suggests that they are related to our narrow perspectives shaped by the colonial and imperial “official”1 written narrative histories of power and dominance. This blog will discuss the support cited for the three reasons identified above.

Separation of the social process of telling the story from the story creates a problem in attributing relevance and meaning. The stories were often told at a potlatch in a ceremony where laws are prescribed through the telling of the story. As important to the telling of the story in this ceremony, is the presence of a listener who is able to witness the telling of the story, and inscribe the laws by repeating them. Hearing the story in absence of the song and ceremony and multi-sensory aspects of the potlatch can render the story confusing and meaningless. If the story is written down and read without the words and songs of the storyteller they can be misinterpreted. If the reader or listener is unfamiliar with the context of the telling and his responsibility of the listening, it will not be understood or repeated properly.

When Indigenous children were removed from their families and communities, the listeners were removed, and thus the next generations’ storytellers. While in the residential schools the Indigenous children were told different stories bythe non-native administrators and communities. They were punished for use of their own languages, so even if they did tell ancestors stories that they remembered later, the language was often lost and interpretation distorted by non-native narrative. Many children and their stories died because of abuse, negligence, or exposure to disease in larger communities. The later listeners of the surviving stories had often lost the language and the ability to hear the story and understand the potlatch ceremony.

Wickwire explains that the listeners of Indigenous stories today cannot hear their message because they have embraced the history as written in the text books and captured by early anthropologists. This history includes Cook’s official1 account of the “discovery” of the west coast of Canada. Cook was sent to make claim on the land for a European imperial power during the Age of Enlightenment. He scientifically remapped and renamed all of the places and told his story (which was edited further by officials in England who did not even observe things first hand). The listener of an Indigenous story today carries many preconceived concepts and histories and finds too many disparate views to his own understanding to listen openly and hear them as the storyteller intended.

Wickwire discusses the impact of one of the 20th Century’s prominent anthropologists, Franz Boas, in limiting our ability to hear the stories of the Indigenous. Boas “collected” some Indigenous stories. They were short and “lifeless” according to Wickwire. Boas and other collectors had edited stories for broad consumption, eliminated community and individual names, and even combined stories. Words like “gun” were removed to transition stories to pre-contact myths.  Wickwire claims that because Boas focused on gathering ancient anthropological “myths” of the Indigenous and did not hear or document their stories of land, generations of readers and writers dismissed these stories as unimportant. The desire was to “collect” a static myth set in prehistoric times. Therefore, many of the stories that were captured to maintain some of the oral histories despite the devastation of the Indigenous because of the removal of the children from their communities, the stories of change and current life were lost or muddled. Boas’ own inability to understand Indigenous storytelling tradition across time and space led him to dismiss many of the stories as “nonsense”. The anthropological collectors dismissing, rewriting and reframing Indigenous stories limited generations of readers’ and listeners’ (and even subsequent documenters of storytellers such as Wickwire) ability to hear what is really being said.

Wickwire claims that because Boas focused on gathering ancient anthropological “myths” of the Indigenous and did not hear or document their stories of land, generations of readers and writers dismissed these stories as unimportant. The desire was to “collect” a static myth set in prehistoric times. Therefore, many of the stories that were captured to maintain some of the oral histories despite the devastation of the Indigenous because of the removal of the children from their communities, the stories of change and current life were lost or muddled. Boas’ own inability to understand Indigenous storytelling tradition across time and space led him to dismiss many of the stories as “nonsense”. The anthropological collectors dismissing, rewriting and reframing Indigenous stories limited generations of readers’ and listeners’ (and even subsequent documenters of storytellers such as Wickwire) ability to hear what is really being said.

Wickwire and Paterson provide compelling arguments as to why we cannot understand the first stories. The necessary continuity of oral ceremonial communication from storyteller to responsible listener was severely interrupted by removing generations of children from communities and families and outlawing their ceremonies. Anthropologists such as Boas and explorers such as Cook told imperial stories and edited Indigenous stories that have been embedded in our consciousness for generations post contact, limiting our ability to hear the real stories.

[1] J. C. Beaglehole, ed., The Journals of Captain Cook on His Voyages of Discovery, Vol. I: The Voyage of the Endeavour 1768-1771 (Cambridge: at the University Press, published for the Hakluyt Society), cxxxvi.

Works Cited:

Cook, James. The Journals of Captain Cook on His Voyages of Discovery, Vol. I: The Voyage of the Endeavour 1768-1771, ed. J. C. Beaglehole. Cambridge: University Press, published for the Hakluyt Society, 1955. Print.

Clayton, Daniel. W. Islands of Truth: The Imperial Fashioning of Vancouver Island. University of British Columbia Press, 1999. Web. 15 February. 2015.

Paterson, Erika. “Lesson 2.2.” ENGL 470A Canadian Studies: Canadian Literary Genres. University of British Columbia, 2013. Web. 16 Feb. 2016.

Robinson, Harry. Living by Stories : A Journey of Landscape and Memory. Talonbooks, 2005. Web. 19 Feb. 2016.

Wickwire, Wendy. “The Grizzly Gave Them the Song: James Teit and Franz Boas Interpret Twin Ritual in Aboriginal British Columbia, 1897-1920”. American Indian Quarterly 25.3 (2001): 431–452. Web 2 Feb. 2016.

While there are certainly some common elements of “home” for our class, I found that there were some unique concepts as well. Although we have a lot in common in our lives in that we are UBC students connected with Vancouver, it is obvious to me that our concepts of home, like many aspects of our thinking, depend upon our histories and where we have been. While several people commented on their connection to land and feeling at home with nature, others spoke much more of emotional spaces and connections as “home”, with no mention of a connection to a place. Sometimes the connection with nature and stimulus from remembered interactions with nature evoked emotional memories of family and home. The change and evolution of nature was tied with the changing concept of home (and decay to some extent). While family was often associated with home and a strong emotional space, most spoke of immediate, living family. A few people spoke of ancestors (in fact Beatrice mentioned 32

While there are certainly some common elements of “home” for our class, I found that there were some unique concepts as well. Although we have a lot in common in our lives in that we are UBC students connected with Vancouver, it is obvious to me that our concepts of home, like many aspects of our thinking, depend upon our histories and where we have been. While several people commented on their connection to land and feeling at home with nature, others spoke much more of emotional spaces and connections as “home”, with no mention of a connection to a place. Sometimes the connection with nature and stimulus from remembered interactions with nature evoked emotional memories of family and home. The change and evolution of nature was tied with the changing concept of home (and decay to some extent). While family was often associated with home and a strong emotional space, most spoke of immediate, living family. A few people spoke of ancestors (in fact Beatrice mentioned 32

I love where we live, but now we have too big of a house for my husband and I, so we will likely move when my youngest daughter goes to university in 2017. My daughters, like most of their friends, feel a need to go away, and find their own home and experience. Cypress Mountain cross country skiing 2016.

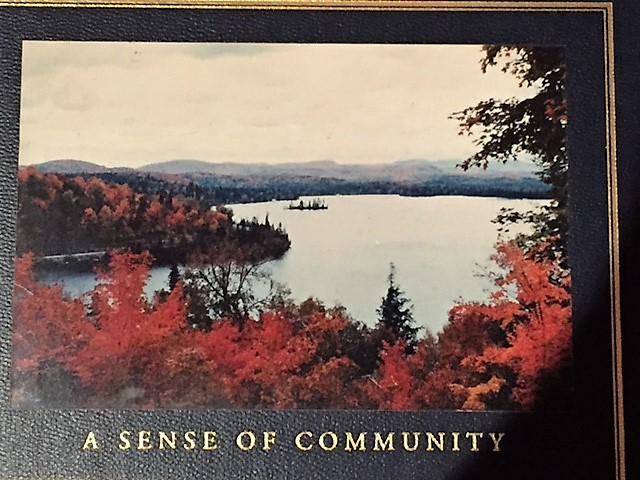

I love where we live, but now we have too big of a house for my husband and I, so we will likely move when my youngest daughter goes to university in 2017. My daughters, like most of their friends, feel a need to go away, and find their own home and experience. Cypress Mountain cross country skiing 2016. My daughters love our little cottage and speak of bringing their children there – it is understood that this is where our family history will continue. They love the sense that their ancestors were there, that everyone returns from all over Canada and the U.S. for these bi-annual events, that there are books written about the community. There is a sense of land, with raspberry patches and wild blueberries. There are wide open fields for children to run free and a clear, clean lake for swimming, canoeing, and skating.

My daughters love our little cottage and speak of bringing their children there – it is understood that this is where our family history will continue. They love the sense that their ancestors were there, that everyone returns from all over Canada and the U.S. for these bi-annual events, that there are books written about the community. There is a sense of land, with raspberry patches and wild blueberries. There are wide open fields for children to run free and a clear, clean lake for swimming, canoeing, and skating. One winter Bear’s mother sent him on a great chunk of ice to find a new place for fish. She looked at the moon to tell him a good place to go, but the moon forgot and Bear

One winter Bear’s mother sent him on a great chunk of ice to find a new place for fish. She looked at the moon to tell him a good place to go, but the moon forgot and Bear