Your blog assignment is to hyper-link your research on the characters and symbols in GGRW — according to the pages assigned to you on our Student Blog page.

Your blog assignment is to hyper-link your research on the characters and symbols in GGRW — according to the pages assigned to you on our Student Blog page.

—————————————————-

PAGES 70 – 80, 1993 Edition, PAGES 85-97, 2007 Edition (referencing will be based on 2007 Edition)

The section that I cover in Green Grass, Running Water, illustrates several of the central themes of the novel: characters on journeys of self-discovery will not find direction in the traditional Christian settler institutions , Native narratives are fluid (with water as the dominant metaphor) and circular and the settler’s insistence on a vacant landscape to be mapped and navigated with linear roads is a fallacy, Native matriarchal creation stories defy the male dominated Christian story, and only through revisiting our stories and circling back to the beginning are Native peoples likely to find that direction. King demonstrates these themes while satirizing settler narratives, myths and institutions and highlighting the missed themes of Native oral narratives.

Alberta Frank Driving

As Jane Flick points out, Alberta’s name is a potential reference to the province in Canada, where King once resided. Additionally, Frank, Alberta was buried in 1903 when the mountain became unstable because of underground coal mining and parallels the risk that Eli fears from the dam. Frank is on the Turtle River, an allusion to the next chapter, where the turtle is part of the Creation story. Additionally, Alberta the land is personified as the shy female that has been colonized by non-Native settlers. Alberta the woman is subjected to figurative colonization by her white husband.

The chapter elucidates the theme of Native people not finding life’s direction following Christian settler institutions and includes many images of roads, trains, cars and maps. As Marlene Goldman points out “the novel intimates that their journeys will never assume a meaningful direction, so long as they stick to the … non-native discursive maps” (Mapping 27). For example, Alberta now rejects the institution of marriage after her own failed first marriage to a stereotypical white male who wanted her to acquire cars and possessions so that she would not “spend the rest of [her] life in a teepee” (GGRW 86) and her drunk father. Not only does Alberta reject marriage, but she seems to reject the settler social conventions of gender and legally binding union of a man and a woman and pursues the tribal affiliations and relations. Alberta’s job as a settler university lecturer does not provide a satisfactory life journey. Her role as lecturer on the Plains Indians ties her to the four Fort Marion Natives who will try to show the lost characters the Native path.

As Alberta reflects on Amos and Ada’s failed marriage one of the novel’s continuing metaphors of water and images of cars being submerged in water surfaces. Amos, who is an abusive drunkard, departs and is not missed while his truck slowly rusts in the water (a lake originally created from the outhouse). Arnold Davidson explains that “the repeated depiction of cars being submerged in water reminds readers that Native tales of origin begin, not with a void to be mapped and driven across, but with water” (Border 121). Furthermore, he suggests that King uses water as part of his narrative strategy to demonstrate the fluidity of Native oral storytelling compared to non-Native linear narratives.

Babo Starts the Story Again

In the next chapter, the police officers are questioning Babo Jones, the janitor from Dr. Hovaugh’s Florida asylum from which the four Indians have escaped. Jane Flick points out that Babo is likely a reference to the black slave in Melville’s Story “Benito Cereno”. The interrogating officers, Jimmy Delano and Sargeant Ben Cereno are also characters from this story. In the Melville story, Babo is thought to lead a mutiny to take the ship to freedom in Africa. King’s Babo in fact mentions that his great-great-grandfather was a barber on a ship (with a cutting blade for shaving). Perhaps King is relating freedom of the slaves to freedom of the Indians in Florida. Jimmy Delano could also be a reference to Columbus Delano who was in the Bureau of Indian Affairs and defended imprisonment of Plains Natives. Marta Dvorak suggests that Melville’s characters are used by King to highlight non-Native white patriarchal imperialism narratives.

Babo is “the native bamboozling the naïve anthropologist” in a “mistold myth” (Abo-Modernist 196) in a story to the officers using oral storytelling as a Native trickster. Babo lightheartedly mistells a Native earth diver creation story, beginning, of course, with water. The talking animals are contrasted with Christian creation stories where only humans are made in God’s likeness. The story of animals swimming in water is in contrast to the biblical story of Noah and the Ark and the story is in another place, not heaven. In a Native narrative style, Babo restarts the story when the ducks get tired of swimming and a woman falls from the sky and sits on a giant turtle and creates dry land. Laura Donaldson suggests that King attempts to displace the Christian foundational narrative of the biblical story of Noah with a new flood myth, perhaps as humorous retaliation for the settler myth that Native Americans were descendants of Noah’s disgraced son, Ham. Furthermore, having the creation story with First Woman is in contrast with Noah’s Christian view that women caused the Fall. Donaldson sees Babo’s stories as Native resistance to settler Christian narratives.

Toward the end of the chapter Babo looks out the window for the Pinto, one of the cars that disappears in the water. Jane Flick mentions that while the Pinto represents one of the many settler vehicles that leads to nowhere for Native characters, it is also potentially a reference to Columbus’ ships or a Plains horse (as drawn by Fort Marion prisoners).

Dr. Hovaugh is interrogated by the officers

The next chapter has Dr. Hovaugh responding to the officers’ questions about the escaped Indians and exposes several non-Native myths. The officers assume that the Natives fit stereotypes including drunken and drugged. Dr. Hovaugh, according to Jane Flick, is a play on the Christian name Jehovah. Dr. Hovaugh represents the white Christian settler-invader imprisoning the Plains Indians with his non-Native myths. Blanca Chester provides analysis of Dr. Hovaugh as Northrop Frye, in “Green Grass, Running Water: Theorizing the World of the Novel”. Dr. Hovaugh is then representative of the rigid classification of literature which precluded oral storytelling or contextual reference to contemporary events. Frye was the promoter of the static Native myth, which aids in the settler narrative of a vacant land and disallows any modern day allusion to challenges to land transfer. Dr. Hovaugh tells of his great-grandfather’s vision, a colonial story of an empty land. His grandfather was “an old world Evangelist” (a Christian – unlike modern day evangelists like Jim Baker) who made his money in real estate (selling land stolen from the now extinct local tribes – a reference to the massacre).

In this chapter King makes reference to 1876. During this year Treaty Six was signed in Alberta with disparity between Native and non-Native interpretation. According to the testimony of Alberta Treaty Six elders, the treaty provided for land sharing, not outright land surrender. Dr. Hovaugh says that “our Indians” arrived (in Florida, also Fort Marion, in 1891, which is just after Wounded Knee, the South Dakota site of the last battle with Plains Indians.

Norma as Matriach and Native stability

As the chapter opens Norma, who takes the unpaved path toward the Sun Dance and is humming a round-dance song, represents Native matriarchal stability. She is taking her nephew Lionel, one of the directionless Natives, back to the traditional Sun Dance and his community. Lionel wonders if Dr. Loomis is still alive and Cecil made it to Wounded Knee. Potentially Dr. Loomis is Reverend Loomis, a Presbyterian minister who contributed to the Centenary Fund in 1889 to pay for Wounded Knee. Lionel recalls looking at his reflection in a window in the past. This could potentially be an allusion to The Picture of Dorian Grey where the character stays the same, while the picture ages and reflects the horror of its environment. Oscar Wilde wrote Picture to put forward the view that art should be pure and not reflect contemporary events, just as Frye felt that Native myth should be timeless and static.

Norma picks up the four Indians at the side of the road, who, like Lionel look lost. Lionel is of course standing in a pool of water, a metaphor for starting at the beginning. References to direction and roads once again signify the challenges of modern life throughout the novel. These Indians are the Fort Marion Indians, Native shape-shifters who can exist in different places and time. John Coleman indicates that the continual reference to the four Indians is a rejection of the colonial Native archetype “as a radicalized Other symbol” (Writing 5) of violence and savagery. The chapter and section closes with reference to the Indian wearing a black mask, to rewrite a stereotype with British literary characters and American Western drama type-cast roles.

GGRW and this section are complex circular narratives that challenge non-Native stereotypes, myths, and historical interpretations with oral storytelling, Native tricksters, creation stories, and narrative structures. These challenges reveal the flaws in the colonial narratives of Canada.

.Works Cited:

Andrews, Jennifer. “Border Trickery and Dog Bones: A Conversation with Thomas King”. Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, [S.l.], june 1999. ISSN 1718-7850. Available at: <https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/SCL/article/view/14248>. Date accessed: 27 mar. 2016.

Chester, Blanca. “Green Grass, Running Water: Theorizing the World of the Novel.” Canadian Literature 161-162. (1999).Web. April 04/2013.

Coleman, John. “Writing Over The Maple Leaf: Reworking the Colonial Native Archetype in Contemporary Canadian-Native Literature.” Bridges: An Undergraduate Journal of Contemporary Connections. Volume 1, Issue 1, Article 3. Wilfred Laurier University. 2013. http://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=bridges_contemporary_connections

Davidson, Arnold E., et al. Border Crossings: Thomas King’s Cultural Inversions. Buffalo;Toronto;: University of Toronto Press, 2003. Web.

Donaldson, Laura E. “Noah Meets Old Coyote, or Singing in the Rain: Intertextuality in Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water”. Studies in American Indian Literatures 7.2 (1995): 27–43. Web 25 March 2016. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.library.ubc.ca/stable/20736846?pq-origsite=summon&seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Dvorak, Marta. “Thomas King’s Abo-Modernist Novels” Thomas King: Works and Impact. Ed. Gruber, Eva. Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2012. 11-34. Web.

Flick Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass, Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162 (1999). Web. March 18h 2016.

Goldman, Marlene. Canadian Literature: Mapping and Dreaming: Native Resistance in Green Grass, Running Water. University of British Columbia Press, 1999. Web. 16 Mar. 2016. https://canlit.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/canlit161-162-MappingGoldman.pdf

Shackleton, Mark. “Have I Got Stories – “ and “Coyote was There” : Thomas King’s Use of Trickster Figures and the Transformation of Traditional Materials”. Thomas King: Works and Impact. Ed. Gruber, Eva. Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2012. 184-198. Web.

Taylor, John Leonard. “Treaty Research Report – Treaty Six (1876)” Treaties and Historical Research Centre, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 1985. https://www.aadnc-aandc.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-INTER-HQ/STAGING/texte-text/tre6_1100100028707_eng.pdf

Wilde, Oscar, and Andrew Elfenbein. Oscar Wilde’s the Picture of Dorian Gray. New York: Pearson Longman, 2007. Print.

Native Dance. Native Dance Partners, Contributors, and Production Team. Carleton University, Editors: Dr. Elaine Keillor, Cle-alls (Dr. John Medicine Horse Kelly), Dr. Franziska von Rosenhttp://www.native-dance.ca/index.php/Renewal/Round_Dances?tp=z

Frank, Alberta Slide: http://history.alberta.ca/frankslide/slidefacts/docs/fsic_facts.pdf

4) In her article, “Green Grass, Running Water: Theorizing the World of the Novel,” Blanca Chester focuses on an analysis of Northrop Frye as Dr. Joe Hovaugh. She writes;

4) In her article, “Green Grass, Running Water: Theorizing the World of the Novel,” Blanca Chester focuses on an analysis of Northrop Frye as Dr. Joe Hovaugh. She writes;

Question:

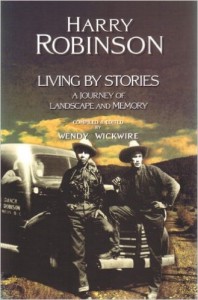

Question: Wickwire claims that because Boas focused on gathering ancient anthropological “myths” of the Indigenous and did not hear or document their stories of land, generations of readers and writers dismissed these stories as unimportant. The desire was to “collect” a static myth set in prehistoric times. Therefore, many of the stories that were captured to maintain some of the oral histories despite the devastation of the Indigenous because of the removal of the children from their communities, the stories of change and current life were lost or muddled. Boas’ own inability to understand Indigenous storytelling tradition across time and space led him to dismiss many of the stories as “nonsense”. The anthropological collectors dismissing,

Wickwire claims that because Boas focused on gathering ancient anthropological “myths” of the Indigenous and did not hear or document their stories of land, generations of readers and writers dismissed these stories as unimportant. The desire was to “collect” a static myth set in prehistoric times. Therefore, many of the stories that were captured to maintain some of the oral histories despite the devastation of the Indigenous because of the removal of the children from their communities, the stories of change and current life were lost or muddled. Boas’ own inability to understand Indigenous storytelling tradition across time and space led him to dismiss many of the stories as “nonsense”. The anthropological collectors dismissing, While there are certainly some common elements of “home” for our class, I found that there were some unique concepts as well. Although we have a lot in common in our lives in that we are UBC students connected with Vancouver, it is obvious to me that our concepts of home, like many aspects of our thinking, depend upon our histories and where we have been. While several people commented on their connection to land and feeling at home with nature, others spoke much more of emotional spaces and connections as “home”, with no mention of a connection to a place. Sometimes the connection with nature and stimulus from remembered interactions with nature evoked emotional memories of family and home. The change and evolution of nature was tied with the changing concept of home (and decay to some extent). While family was often associated with home and a strong emotional space, most spoke of immediate, living family. A few people spoke of ancestors (in fact Beatrice mentioned 32

While there are certainly some common elements of “home” for our class, I found that there were some unique concepts as well. Although we have a lot in common in our lives in that we are UBC students connected with Vancouver, it is obvious to me that our concepts of home, like many aspects of our thinking, depend upon our histories and where we have been. While several people commented on their connection to land and feeling at home with nature, others spoke much more of emotional spaces and connections as “home”, with no mention of a connection to a place. Sometimes the connection with nature and stimulus from remembered interactions with nature evoked emotional memories of family and home. The change and evolution of nature was tied with the changing concept of home (and decay to some extent). While family was often associated with home and a strong emotional space, most spoke of immediate, living family. A few people spoke of ancestors (in fact Beatrice mentioned 32

I love where we live, but now we have too big of a house for my husband and I, so we will likely move when my youngest daughter goes to university in 2017. My daughters, like most of their friends, feel a need to go away, and find their own home and experience. Cypress Mountain cross country skiing 2016.

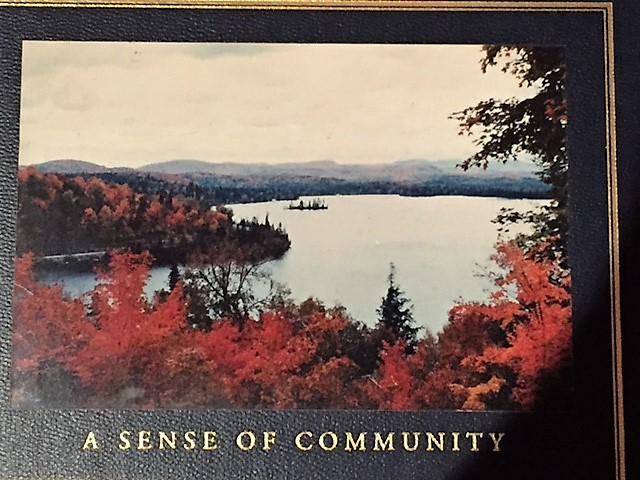

I love where we live, but now we have too big of a house for my husband and I, so we will likely move when my youngest daughter goes to university in 2017. My daughters, like most of their friends, feel a need to go away, and find their own home and experience. Cypress Mountain cross country skiing 2016. My daughters love our little cottage and speak of bringing their children there – it is understood that this is where our family history will continue. They love the sense that their ancestors were there, that everyone returns from all over Canada and the U.S. for these bi-annual events, that there are books written about the community. There is a sense of land, with raspberry patches and wild blueberries. There are wide open fields for children to run free and a clear, clean lake for swimming, canoeing, and skating.

My daughters love our little cottage and speak of bringing their children there – it is understood that this is where our family history will continue. They love the sense that their ancestors were there, that everyone returns from all over Canada and the U.S. for these bi-annual events, that there are books written about the community. There is a sense of land, with raspberry patches and wild blueberries. There are wide open fields for children to run free and a clear, clean lake for swimming, canoeing, and skating. One winter Bear’s mother sent him on a great chunk of ice to find a new place for fish. She looked at the moon to tell him a good place to go, but the moon forgot and Bear

One winter Bear’s mother sent him on a great chunk of ice to find a new place for fish. She looked at the moon to tell him a good place to go, but the moon forgot and Bear