- Explain why the notion that cultures can be distinguished as either “oral culture” or “written culture” (19) is a mistaken understanding as to how culture works, according to Chamberlin and your reading of Courtney MacNeil’s article “Orality.

The view that cultures can be separated into “oral culture” and “written culture” is a flawed conception of how culture works according to J. Edward Chamberlin in If this is Your Land, Where are Your Stories? and Courtney MacNeil’s Orality. Chamberlin defines “oral cultures” as those “whose major forms of imaginative expression are in speech and performance” (Stories 18) and “written cultures” are generally considered those that use alphabetic writing. MacNeil identifies that orality can be defined as the means through which we exchange information and as a media in competition with other forms. It is important to examine the rational arguments Western readers require to see the flaws in the concept so that they can begin to transition thinking away from use of the distinction to divide “them and us”, the “civilians and barbarians”. This blog will show how Chamberlin and MacNeil demonstrate the errors in the concept of separated cultures through illustration that many oral cultures are abundant in non-syllabic writing and many written cultures have oral traditions.

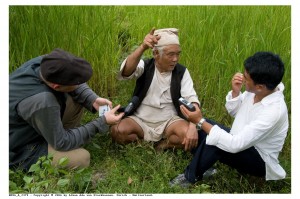

Chamberlin rejects the distinction between oral cultures and written cultures as a “misconception” (Stories 19) that entrenches the divide between peoples and dismisses as primitive those from cultures considered to be oral. To dispel the myth that there are exclusively oral cultures, he identifies the non-syllabic writing that take the same prominence in the society as written texts do for cultures using alphabetic writing. Such non-syllabic writing includes various weavings, carvings, masks, hats, and strings. Princeton Professor of linguistics Joshua Katz said that the majority of modern English texts use only twenty words, whereas Father Cobo in History of the Inca Empire: An Account of the Indians’ Customs and Their Origin, Together with a Treatise on Inca Legends, History, and Social Institution explains that indigenous Andeans from the Inca empire used quipos (made of rope) with an infinite number of knots and many colors to tell such complex and subtle histories that specialists, “quipo camayos” were required to maintain them and “read” them. The Incan Andeans were considered illiterate (and thus inferior) by the Spanish because they did not have an alphabetic language. As Chamberlin claims, “written” language can take many forms.

Chamberlin then identifies how European cultures, considered written cultures for several centuries, have well established, ritualized oral traditions for some of their most important institutions such as churches, parliaments, schools, and courts. In addition to these highly formalized oral traditions, he identifies the role of oral stories, songs, rhymes, anthems and myths in many cultures’ creation stories and ceremonies of belief. Furthermore, he identifies that “finding consolation requires ceremony” (Stories 102) as he talks about how many non-alphabetic and alphabetic cultures, including 20th century Americans, use dirges, poems, and songs for emotional support. Oral traditions form a fundamental part of many cultures, including those who use alphabetic written language.

MacNeil quotes Chamberlin as she agrees with him that “speech and writing are so entangled with each other in our various forms” (Orality) and advances his arguments through discussion of how the many technological advances, namely cyberspace, have demonstrated how natural this entanglement is for humankind. She also rejects the view that orality is primitive and that written language is key to the evolutionary process as espoused by those such as Walter Ong and Marshall McLuhan. (In this short video Ong argues that oral cultures are inferior because they cannot create scientific treatises: Walter Ong – Oral Cultures and Early Writing https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uvF30zFImuo.) She says that their claims that orality is ephemeral is wrong as clearly demonstrated with audio files and the explosion of such applications as YouTube. Conversely, applications where written communications will disappear after reading such as Snapchat belie the permanence of the written word! This explosion of integration of the oral and written shows the natural way that cultures work.

MacNeil, like Chamberlin, expands upon the use of orality as a broad human way of “accessing collective memory or innate human truth” (Orality) in such forms as laments, dirges, or slam poetry. She defines these forms as part of meschonnic orality, the fundamental way that humans access an interior drive toward interaction and connection. In many cultures, even those with extensive written language, orality is still the overriding art form and an essential part of the arts. MacNeil concludes that despite evolution and modernization, most of us use orality as the main means of communication.

Chamberlin and MacNeil illustrate how cultures are both oral and written and how digital and non-digital cultures weave both together. Understanding this allows us to step back and question our interpretation of the written word as “the truth” and the spoken, sung, or chanted word as inferior. McLuhan predicted in 1965 that “world connectivity” would bring us to “wholeness” (The World is Show Business: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NNhRCRAL6sY). As Tom Pettit says “print literacy is an exception in a much longer trajectory of human thought, which may be in the process of restoring earlier modes of communication based on speech and instantaneity rather than space and time-delay” (After Ongism 207).

Works Cited

Chamberlin, Edward. If This is Your Land, Where are Your Stories? Finding Common Ground. Toronto: AA. Knopf, 2003. Print.

Cobo, B. History of the Inca Empire: An Account of the Indians’ Customs and Their Origin, Together with a Treatise on Inca Legends, History, and Social Institutions. University of Texas Press, 2010. Web 11 Nov 2015.

Courtney MacNeil, “Orality.” The Chicago School of Media Theory. Uchicagoedublogs. 2007. Web. 19 Feb. 2013.http://lucian.uchicago.edu/blogs/mediatheory/keywords/orality/

Hartley, John. “After Ongism, the Evolution of Networked Intelligence” Orality and Literacy, London: Taylor and Francis, 2013. Ebook Library. Web. 21 Jan. 2016.

McLuhan, Marshall. The World is Show Business: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NNhRCRAL6sY

Ong, Walter. Oral Cultures and Early Writing https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uvF30zFImuo

4 responses to “Assignment 1.3: Are there Oral and Written Cultures?”