Gap Analysis

This past year feels like one, ongoing gap analysis. The more I’ve learned, the more gaps I see and it’s like I’m just trying to catch up my programming with my learning. Part of my drive and why I’m in this program is to address the gaps that people in my field aren’t currently addressing: tactics, as I’ve written about previously, is one but mental skills are the other. When it comes to mental skills, there is this idea that an official either has it or doesn’t. There’s no reason to believe that attitude is because decision-makers don’t value mental skills – no one with whom I’ve spoken has ever denied the importance of mental skills. Rather, this programming gap stems from a lack of expertise and understanding of how to build those skills.

The result is that mental skills are something that is “addressed” rather than built. Once a year, a performance “expert” (using the term expert very loosely, in some cases) makes a presentation at a training camp. This is usually something along the lines of “here are four tools to use in [X] situation”. It’s less of a mental training program and more the personification of a self-help Instagram post. We never really progress beyond the basics and there is no sense that we are building towards a defined end goal. This reality is reflected in the Hockey Canada officiating performance standards, in which the only mental skills measured are “attitude” and “reaction to pressure”. These are intended to be rated on a scale of 0-5 and 0-10 respectively but without clear benchmarks through which to make those judgements. No standardization means no reliable data, to which one could fairly ask: what’s even the point?

This system gap creates an athletic gap. Officials not only lack the mental skills to perform but also any clear idea of how to build those skills. They may take the disparate skills picked up from a lecture here or a webinar there and try to apply them on their own but, even if they achieve a modicum of success, they have no real way of measuring that success. The outcomes of this situation are threefold: 1) officials are left to succeed and fail based on their natural mental talents; 2) officials who have other skills come up against an invisible barrier and fail to progress/leave the program out of frustration; and 3) a further system gap is created because the program may invest in officials and subsequently promote them, only to have them fail because their mental skills were insufficient for that next level. Therefore, it is in the best interests of all parties to ensure a robust framework for the training and evaluation of mental skills.

Establishing the Baseline

As discussed in the previous section, current practices up to this point have left us with no baseline. Therefore, we cannot even ask what we should expect in terms of mental performance for an elite official and how we might measure it. One of the key limitations of my Gold Medal Profile assignment for KIN 515, particularly in the psychological domains, is that while I drew my benchmarks from scholarly, peer-reviewed research, I was necessarily transferring concepts and models from other sporting domains – often combining or using related but separate methods to infer conclusions. As a result, my program objective is to begin establishing baseline methods and results that can be used to produce useable data and conclusions.

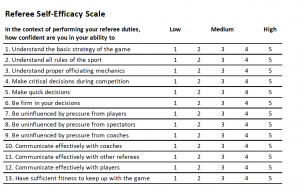

My athlete objective is obviously to improve the mental skills of the athletes. In the hopes of measuring this baseline, I am using a multi-sport tool, known as the Referee Self-Efficacy Scale (Myers et al., 2013). This tool has been validated across a variety of sporting contexts and the officials have completed this recently and will complete it again prior to the start of the season. In the absence of more comprehensive baseline readings, I hope that this will provide me with some measure of whether or not these interventions are successful.

Session #1

In order to begin this process, I proposed an ideal outcome, based on Clough, Earle, & Sewell’s (2002) “4 Cs” of mental toughness. We want our athletes to possess confidence, which is drawn from a commitment to maintaining the course through stress, the belief that they have control over their experiences, and the view of stress as a challenge that is a natural part of their development. Elite officials naturally possess a sense of control, as the very discipline commits to enforcing order on the chaos of sport and the female officials in this group are inherently committed because they came through male-dominated environments, experiencing discrimination as well as natural obstacles, to reach this point. Therefore, I drew our focus to the view that stress is a challenge that is a natural part of development.

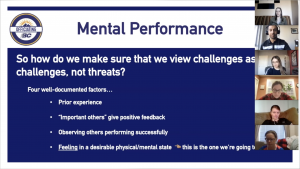

One thing I was conscious of, particularly in the context of an ongoing, 14-month global pandemic, was that I didn’t want the officials to feel discouraged – as if we were starting from zero. As we build towards the 4Cs, I wanted to present a framework in which the officials already had a most of the tools they needed, even if we still had a long way to go. To that end, I looked to Jackson, Beauchamp, & Dimmock’s (2020) four antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs: prior experience, positive feedback from “important others”, observation of other performing successfully, and feeling in a desirable physiological and mental state prior to performance. I illustrated how and why they all possessed the first three and we were going to focus on the last one: ensuring they could consistently feel in a desirable state, prior to competition.

We spent the balance of the first session trying to describe their “desirable states”. I had asked them to prepare by thinking about competition situations where they felt good. We focused on the emotional and cognitive aspects, thinking of the pre-competition state, rather than the competitive performance itself. For the most part, athletes were able to recall those performances fairly easily. One minor area of concern was the number of aspects that involved another person (for example, feeling comfort with a particular teammate) as team assignments are outside of the athlete’s control, particularly at the national and international levels. However, irrespective of this concern, the next step will be to analyze where those feelings and thoughts come from, so that they can be replicated.

Session #2

This session was really an extension of the previous one. The goal of Session #1 was to describe the ideal pre-competitive state, the goal of Session #2 was to analyze the “why/how” behind that state. It should be noted that our methodology is driven by Hanin’s “Individual Zones of Optimal Functioning” and the notion that while there are universal “goalposts”, the definition of the ideal pre-competitive state is ultimately determined by the athlete. From that perspective, the why/how of the pre-competitive state is where the coach expertise becomes important – both from the perspective of sporting expertise but also by facilitating the production of information.

The process was highly repetitive, so I won’t re-hash the entire thing, both for the reader’s sanity and for mine. But some common statements and clarifying questions include:

- I felt rested.

- How much did you sleep? What was your sleep quality? What time did you go to bed and get up? Did you have a nap prior to the game? Were you at work or school? What was your training like on the day before? Did you feel ready walking into the building or did you get ready through your warm-up?

- I was excited for the game itself.

- What were you excited for? In your mind, when you imagine a “good” hockey game, what are you thinking of? What does that look like when the puck goes down?

- I felt focused/in control.

- What does “focus” (or lack of focus) look like? What specifically are you focusing on? Are you consciously or unconsciously focusing? Did you do anything to get “focused”?

As we progressed through the second session, I was a little concerned at the lack of depth of some of the answers. Admittedly, it is difficult to run through these in a virtual, group setting. However, at this point in the ongoing global pandemic, I refuse to continue deferring crucial tasks to a hypothetical future date when we can gather in-person. Moreover, despite my presentation of a framework in which the officials already had the majority of the skills required for success, the reality is that we are starting from zero from a deliberate practice perspective. These athletes have never been asked to interrogate their own performance to this extent. So, there is reason to believe that more deliberate self-reflection will yield improved results, which will allow us to progress to the next phase.

Moving From Pre-Competitive State to Competitive State

The ultimate goal of this process is to produce an individual mental performance checklist that officials can begin to utilize when exhibition games resume (hopefully) in August/September. Once we have the ideal pre-competitive state finalized, we will shift to the competition itself. As mentioned previously, one of the four antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs is prior experience. However, in officiating, there will always be a new experience or an experience that is not directly analogous to a previous experience. An official will arrive at a National or World Championship and they have no pre-competition environment to “get a feel” for the action and the teams. This is particularly true at the international level, as officials can be promoted through the pyramid year-after-year. However, the end result is that an official may step on the ice at a certain level for the first time and their performance in that game could make or break their entire tournament. Naturally, this can be rather anxiety-inducing and, as a program, we see it as our responsibility to prepare officials for that reality.

Although we aren’t yet ready to move from thinking about the pre-competitive to thinking about the competitive, I have a few considerations in my mind that will inform our progress. The first is that refereeing places a heavy cognitive load on officials. Their primary task, which is to ensure a safe and fair game, relies primarily on cognitive skills. The physical actions of officiating are more of a facilitator than anything else. Therefore, the goal of training must be to automatize as much of their actions as we can, because it is simply impossible to consciously think through every action while shouldering the cognitive demands of an elite hockey game. At a certain point, an official has to look at a play and just know where they need to be, without consciously considering all the variables.

The second consideration is that external focus facilitates the production of effective and efficient movements (Sabiston, Pila, & Gilchrist, 2020). So, while our current mental training is highly internally-focused, once we have a handle on that, we should be shifting focus to external checkpoints that indicate successful application of mental skills. The third consideration is that despite the importance of prior experience in developing self-efficacy beliefs, an individual can elicit emotions just as strongly from imagining a scenario as they can from remembering a real scenario (Janelle, Fawver, & Beatty, 2020). With that in mind, it should be possible to effectively train mental skills that will be activated during games, even during the preparatory phase.

Future Directions

The process that I have outlined above is planned to take us from April through to early September, when our competitive phase usually begins. Of course, this comes with the now-mandatory disclaimer that the success of any plan, no matter how intelligently thought out, hinges on the whims of the Covid pandemic but hope springs eternal. By the time we enter our competitive phase, these officials should have detailed performance plans for ideal pre-competitive and competitive mental states.

Presumably, improved mental skills will benefit their performance, which is, of course, the ultimate objective of all of this. However, it will also provide us, as a program, with baseline readings. We will re-administer the Referee Self-Efficacy Scale at the conclusion of this process, which will hopefully reflect a positive change. Additionally, as the competitive phase gets underway, we will begin administering the Competitive State Anxiety Inventory 2R questionnaire prior to each game, which will help us measure the anxiety and self-confidence of the officials prior to entering the competitive environment. By ensuring that athletes are educated and trained in their mental preparation, we can begin to critically evaluate not only our programming but their responses and performances.

The true challenge is that I cannot see inside these athletes’ heads. I can provide an empirically-based framework and expert guidance but the ultimate success depends on the ability of the athletes to interrogate themselves and their own practices. As control freak detail-orientated person, that uncertainty hangs over my planning like a dark cloud. Having said that, I am blessed with a focused, resilient group of athletes and I am confident that we can do it. Ultimately, I believe establishing this baseline will open up new roads for us in terms of research and programming with the ultimate goal of performance excellence on the ice.

Works Cited

Clough, P. J., Earle, K., & Sewell, D. (2002) Mental Toughness: The Concept and Its Measurement. In I. Cockerill (Ed.), Solutions in Sport Psychology (pp. 32-43). London: Thomson.

Cox, R. H., Martens, M. P., & Russell, W. D. (2003). Measuring anxiety in athletics: The revised competitive state anxiety Inventory–2. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 25(4), 519-533. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.25.4.519

Myers, N. D., Feltz, D. L., Guillén, F., & Dithurbide, L. (2012). Development of, and initial validity evidence for, the referee self-efficacy scale: A multistudy report. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 34(6), 737-765. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.34.6.737

Ruiz, M. C., Raglin, J. S., & Hanin, Y. L. (2017). The individual zones of optimal functioning (IZOF) model (1978-2014): Historical overview of its development and use. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 15(1), 41-63. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2015.1041545

Tenenbaum, G., Eklund, R. C., Wiley Online Library, & Wiley Frontlist All Obook 2020. (2020). Handbook of sport psychology (Fourth ed.). Wiley.