The final thought… first

I’ve decided to put my final thoughts first because something changed in my life recently and I didn’t want to completely re-write my portfolio but I thought it should be included, so here goes…

I love the Grouse Grind trail in North Vancouver, not because I like the outdoors (I don’t), but because it forces me to push myself. I’m on the mountain and the only way off is to keep climbing another 853 metres at a 31% grade… so if I want to be done, I’d better get on with it. And, because of the nature of the trail, there’s nothing to see. So I grind away, putting one foot in front of the other, until I get to the top. When I reach the top (and once my chest is done heaving) I turn around, and laid out beneath me is an incredible panoramic view of Vancouver and the Georgia Straight. But I don’t go for the view; I go for the journey up… the view is just a nice bonus.

My coaching career, up to this point, has felt a little bit like that. I dabbled in coaching hockey teams and that was fine but it wasn’t really my passion. While I was coaching teams, I didn’t have that desire to really commit to my coach education and build my skills — I was just happy to be there. Then, I started coaching officials and not only did I love it but I felt like I could make a difference. I was invested with more and more responsibility and starting climbing the ranks, from my local association to increasing responsibilities with my provincial sport organization. Then, I realized I’d hit a ceiling and so I started racking up coaching courses and NCCP points, which eventually led me here, to the HPCTL program. Throughout this process, I’ve been teaching high school, which I feel very passionate about and I’ve wanted to do since I was in high school. I never thought about my coaching journey in terms of the end product — I was perfectly happy just to be on the mountain, grinding away.

And while I’ll always be focused more on the journey than the destination, I did hit a milestone this past Tuesday, when I signed a contract to join Hockey Canada’s full-time staff. As manager of the officiating program, overseeing every one of Canada’s 35,000 ice hockey officials, from the grassroots to the Olympic-bound. I knew this job existed and, if you’d asked, I would have said “sure, it would be cool,” but I never really thought seriously about how to make that happen. Yet, as it turns out, everything that I’ve done over the last ten years has led me perfectly to this one moment, last week, when they put a contract in front of me and offered to make my passion my full-time job.

So, who knows how this will turn out? As I said to my wife, this could be the job that completely changes my life and that would be awesome. On the other hand, I could also be back in a classroom in 5 years and that would be disappointing but not the worst thing. But I’ve worked hard, especially over the last 4 years. Every week, I’ve gone to my classroom and been with my students, with the mental and emotional commitment that job demands; and then, most nights I’d come home and head off to a rink or hop on a Zoom call or answer emails or leave work on Friday and drive straight to the Okanagan or Vancouver Island for a weekend of hockey. And I loved it — it was exhausting but I loved it — and I was happy to be on that mountain, grinding away. But, at this moment, turning around to see the view from the top is pretty sweet.

So, I’m glad that I went through this practicum process so that I could leave my current program in good hands for my replacements (strong succession plan in place) and that I can jump into this new role with my head full of new ideas and my skills as sharp as they ever have been.

The Practicum Reflection

Having now completed my portfolio, mentor meeting, and final presentation, I can look back at this year with a great deal of satisfaction. Obviously, we would have preferred to go through the last year without the restrictions of the pandemic and we had to do a lot of scrambling in our coursework to accommodate those restrictions. However, I feel like this year pushed me to think outside of the box and come up with creative applications of research and interventions. This was reflected in my final portfolio and I will discuss some highlights here…

My original goals for the practicum were as follows:

- Construct robust performance standards for talent identification and evaluation

- Adapt in-game coaching protocols, in line with performance standards

- Framework for video coaching that engages with best practices for use of video

- Training camp goals & objectives to maximize efficiency

- Job descriptions and staff communication plans to align our growing staff

As a result of the Covid pandemic, the theme of my portfolio was more about the process of learning and development to ameliorate athletic and system gaps, rather than the accomplishment of specific objectives. Many of these objectives were simply not possible to achieve in the way that I had originally imagined. I originally drafted my objectives in late October and within six weeks, we were shut down for the season. Regardless, I believe I was able to make meaningful progress in these areas and I consolidated my objectives into four parts:

- Performance standards

- Video coaching

- Training camps objectives

- Coach Education

I won’t go into the specifics of each aspect because that is detailed in my portfolio but I will briefly cover the next steps for each.

1. Performance Standards

I made great progress on my Winning Style of Play/Refereeing and Gold Medal Profile. This is particularly important for elite referees because this level of performance planning doesn’t exist. So, a validated WSP/GMP would be extremely valuable. However, because of the lack of rigorous scholarship on officiating ice hockey, more research is required. Therefore, there are some things to consider moving forward:

- Is the scoring system too cumbersome to apply/assess in game situations?

- How do you ensure inter-rater reliability?

- How do we ensure that coaches do not rely on the scoring system at the expense of anecdotal feedback

- How should the criteria be weighted to reflect the relative importance of these skills/KPIs?

Projecting into the future, I believe the GMP will eventually split itself into two categories: game-to-game performance indicators and long-term measures of success. Game-to-game performance indicators would ultimately represent very few of the performance standards in the GMP. These are aspects that would be useful in a game-to-game measurement, including: positioning errors, penalties called/not called, communication, and emotional restraint. The second, larger, category consists of aspects that are either too difficult to measure, not relevant, or fluctuate too greatly on a game-to-game to be useful. However, measuring them over a longer period of time (i.e. over a season or an Olympic cycle) could provide us with the data to confidently rank one official above the other.

2. Video Coaching

In the last 10 years, video has gone from a luxury in amateur sport to a staple; even at a U11 game, I’ll see someone’s dad with an iPad, live-streaming the action. With this tool comes both benefits and pitfalls and the research is clear: the tool is positive, if used correctly.

The most common use of video in officiating is to identify and dissect isolated clips of a foul. However, during the 2020-21 season, I was able to implement two intervention via video-based platforms that returned promising initial results. As the season got underway, we made a group decision to limit virtual training hours, due to the uncertainty around game action and the high volume of online hours necessitated by working and attending school from home. So, our implementation was limited in terms of time and scope but the initial results present promising directions for further innovation and growth in this area. So, moving forward into next season, the question is how we can continue to use video along these lines, in addition to traditional methods.

3. Training Camp Objectives

As a geographically distributed program, our face-to-face training time is both limited and valuable. Since 2017, when I took over the program, we have held at least three centralized training camps per year and I am pushing to add a fourth.

What is interesting is that as I push to expand our training camps, other officiating programs are cutting back their offerings. In discussions with other leaders, the primary motivation for reducing or cutting training camps was cost. This is understandable and a major hurdle for our program as well. However, there was also a not-so-subtle implication that they felt training camps were not a valuable use of money and time. I find it difficult to believe that having athletes in one place for centralized training and development is not valuable. Therefore, with the greatest respect to my colleagues, I must conclude that the de-valuing of training camps is an individual issue, rather than a methodological one.

Moving forward, the objectives and training focuses that I identified, will help us quantify the progress made from our training camps. Have we hit our objectives? Are we maximizing the efficacy of our limited face-to-face training time? Moreover, if there is the possibility to secure additional funding, our objectives will help us justify that additional funding.

4. Coach Education

The initial objectives around the topic of coaching were around in-game coaching protocols and management of the coaching staff. However, one result of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic is that there were few, if any, takeaways from this season from an in-game coaching perspective. One of my goals in undertaking a Master’s degree was to elevate the practice of coaching within the officiating community. To that end, my involvement in the HPCTL program has been invaluable. My professional training is as a teacher and in education, we talk about the concept of a “community of practice”. Because “officiating coaching” is in its infancy, I have struggled to find that community of practice in my hockey circles. However, coming into the HPCTL program, a space that is designed to be multi-sport, I found an opportunity to discuss and share with my peers who were also approaching the practice of coaching form a high conceptual level.

The concept of coach education obviously extends beyond the high performance level, and I believe it will be the rising tide that lifts all boats. A coach education initiative that addresses all levels of the game will naturally raise the quality of coaching and create that community of practice that is not exclusive to the high performance sphere. The appetite for education is there; I’ve seen it first-hand. It is a failing of PSOs and the NSO that the framework doesn’t already exist. I am looking forward to being an architect of this framework in our officiating community of practice.

Tying it All Together

The biggest change that I’ve noticed in my coaching context over the last 12-24 months is that people are catching up. Previously, I would present to a room and everyone would look around and nod and say “wow, yeah, we’d never thought of that”. Now, I present to a room and people ask clarifying questions — they challenge me. As people working in high performance sport, we know that no matter how much you hold yourself accountable, having other people pushing you is what will take you to a whole other level. So I’m looking forward to my new job, where I will have the opportunity to surround myself with the best and relish the challenges that lay ahead. Thank you, everyone, for reading along and joining me on this journey. Hopefully, we’ll see each other back here in September.

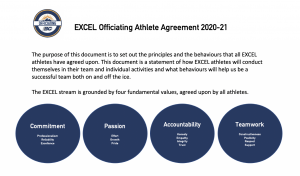

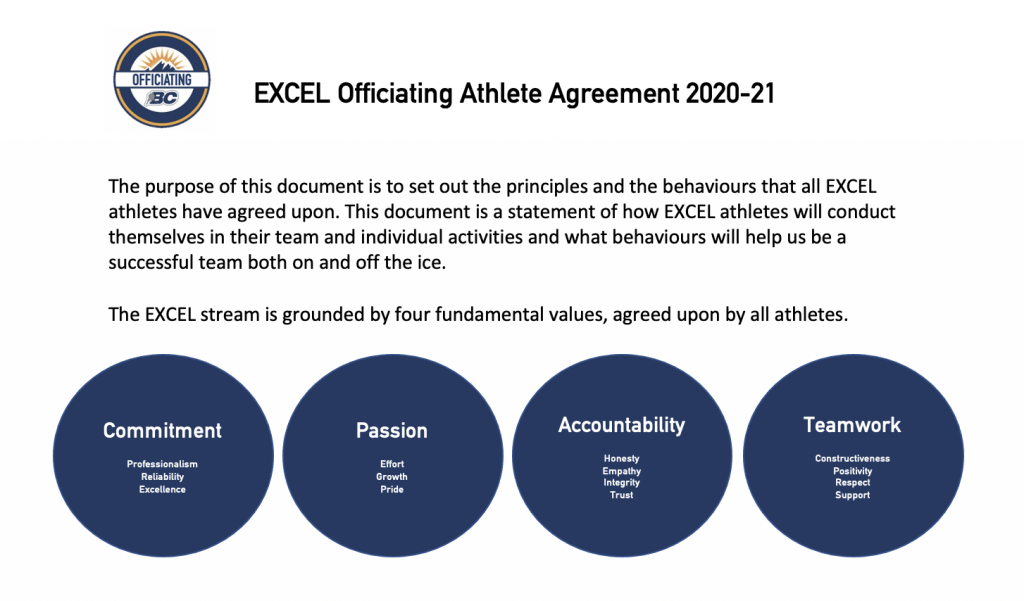

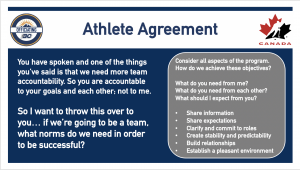

The training camp was 52 hours of intense physical and mental training that could not have been accomplished remotely but the one piece that I want to focus on in this post is the creation of our first athlete agreement. This is not something that I had embarked upon previously because my coaching context is so diverse: I’m working day-to-day with individuals from sixteen to forty-five years of age across the Train to Train, Train to Compete, and Competitive for Life contexts. Under those diverse circumstances, it’s difficult to come to a shared understanding. However, I don’t want to coach in a context where I am the one driving the expectations because ultimately, it is the athletes who have to do the work and it is their conceptions of success or failure that drive our program goals and my coaching goals.

The training camp was 52 hours of intense physical and mental training that could not have been accomplished remotely but the one piece that I want to focus on in this post is the creation of our first athlete agreement. This is not something that I had embarked upon previously because my coaching context is so diverse: I’m working day-to-day with individuals from sixteen to forty-five years of age across the Train to Train, Train to Compete, and Competitive for Life contexts. Under those diverse circumstances, it’s difficult to come to a shared understanding. However, I don’t want to coach in a context where I am the one driving the expectations because ultimately, it is the athletes who have to do the work and it is their conceptions of success or failure that drive our program goals and my coaching goals.

The other thing that occurred in moments of conflict was that two of the athletes in the group, who I would categorize as being “less outspoken” than others, fell back on the communication model of a “I see; I think; I feel; I need” message (Coaching and Leading Effectively, 19), which I first introduced at our High Performance Training Camp (all 40 athletes from across the province) in August 2019. I was totally blown away by this because while I believe in the efficacy of this technique, it always seems a little hokey to be practicing and roleplaying a technique like this. So while everyone participated in the exercise and some mentioned it in their feedback forms, there was no way for me to tell whether or not anyone had actually taken this to heart. So it was extremely validating that, in a moment of challenge, where I might have expected individuals to shrink away from interpersonal conflict, they a) rose to the occasion and didn’t back away; b) engaged with a technique that I introduced to the group over a year ago; and c) they were able to deliver a message respectfully and effectively, in a way that contributed value to the conversation.

The other thing that occurred in moments of conflict was that two of the athletes in the group, who I would categorize as being “less outspoken” than others, fell back on the communication model of a “I see; I think; I feel; I need” message (Coaching and Leading Effectively, 19), which I first introduced at our High Performance Training Camp (all 40 athletes from across the province) in August 2019. I was totally blown away by this because while I believe in the efficacy of this technique, it always seems a little hokey to be practicing and roleplaying a technique like this. So while everyone participated in the exercise and some mentioned it in their feedback forms, there was no way for me to tell whether or not anyone had actually taken this to heart. So it was extremely validating that, in a moment of challenge, where I might have expected individuals to shrink away from interpersonal conflict, they a) rose to the occasion and didn’t back away; b) engaged with a technique that I introduced to the group over a year ago; and c) they were able to deliver a message respectfully and effectively, in a way that contributed value to the conversation.