“Strange and mysterious things, though, aren’t they – earthquakes? We take it for granted that the earth beneath our feet is solid and stationary. We even talk about people being `down to earth’ or having their feet firmly planed on the ground. But suddenly one day we see that isn’t true. The earth, the boulders, that are supposed to be solid, all of a sudden turn as mushy as liquid” (from `after the quake’ by Murakami Haruki).

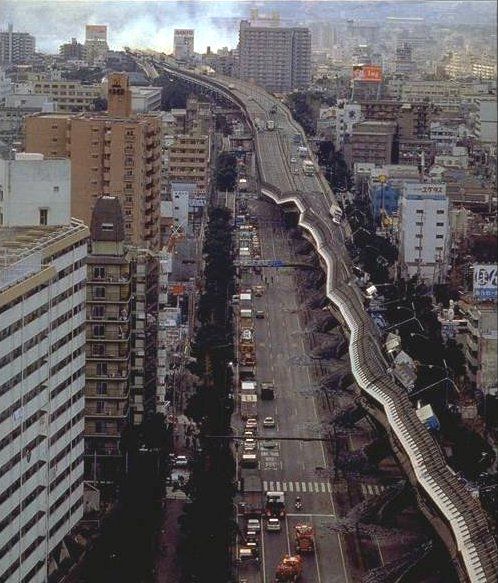

I have long wanted to tell the story of Kobe’s reconstruction following the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, an episode that led to the loss of over 6,000 lives and which destroyed over 200,000 homes. An earlier essay, written with colleagues Tom Hutton and Michael Leaf, was published by The Japan Foundation. When the disaster struck early in the morning of January 17th, 1995, I was living with my own family in Kyoto, Japan, a city just outside of the Hanshin disaster zone. The apartment we resided in `shook and rattled’ and soon after it was announced on the radio that while Kyoto had experienced a level 5 quake the epicenter was close to Kobe in Awaji Island. Telephone lines to the disaster stricken area were cut, and it was only later that news reports began to give details of the destruction. On that day, the earth around Kobe without doubt turned `as mushy as liquid’. Ten years later, a sabbatical in Japan allowed me to reflect on what had taken place in terms of the city’s recovery. My study of Kobe’s recovery from the earthquake up to early 2005 reveals the essential complexity of reconstruction planning following disasters. The long-term recovery of cities affected by natural calamities differs significantly from the provision of immediate post-disaster rescue and relief. While speed remains important, proper planning becomes even more crucial. Putting up temporary housing is relatively fast and easy, but rebuilding a viable and vibrant community is not. This study encompasses issues related to land use changes, urban governance and economic recovery. It is based on field investigations conducted between 1995 and 2005 and interviews with Kobe’s planners, economists, consultants, academics and national government officials. I explore the twin themes of `crisis’ and `opportunity’ in order to bring to light the city’s reconstruction objectives after the quake. In addition, I employ a framework derived from the literature on post-disaster reconstruction in order to understand the influence of prior circumstances in Kobe, the geography of the earthquake impact, aspects of government actions and community responses.

The earthquake and the ensuing fires that devastated parts of Kobe presented opportunities to rebuild districts that city planners had been unable to touch before, and to secure funds from the national government for novel infrastructure projects. Both Kobe city and Hyogo prefecture issued long-term plans for the rejuvenation of the Hanshin area – such as the `Phoenix Plan’, an ambitious serious of projects designed to vault Kobe ahead of its competitors. These schemes provided an opportunity for new approaches and high-profile urban development. Nevertheless, they were challenged – at least initially – by citizens who felt vulnerable and disempowered in the period following the quake. Accordingly, Kobe’s planners had to win back community trust through the use of an extensive local consultation process – known in Japan as machizukuri. Through case studies, the research indicates that the ability to rebuild stricken neighbourhoods was decidedly problematic. In part this was due to aspects of Japan’s style of urban redevelopment. The study shows also that reconstruction outcomes and rates of recovery were highly differentiated within Kobe itself. By 2005 the construction of key `symbolic infrastructure’ projects (such as museums and an enterprise zone) formed a key part of the city’s rebuilding, and many of these were fully completed and operational within the 10-year reconstruction period. However, it is doubtful whether they were well-connected to the long-term improvement of the local economy.

Overall, the study confirms the inherent complications involved in reconstruction after a major disaster while pointing to cultural features specific to the Japanese model. There are many lessons from the Kobe disaster and reconstruction planning to be learned for other Japanese cities and, more generally, for disaster-prone areas in other countries around the world. Above all else, a study of the Hanshin earthquake shows many parallels between the Vancouver and the Lower Mainland area of British Columbia and Kobe. Both Vancouver and Kobe are port cities around 1.5 million people, both have large areas subject to liquefaction (land subsidence after earthquakes) and both have a mix of old and new construction. For that reason I hope Kobe’s experience can in some way inform pre-disaster plans for reconstruction in my own community. A book-length manuscript is currently being finalized for publication by a university press.

Research Report:

D.W. Edgington, T. Hutton and M. Leaf (1999) The Post-quake Reconstruction of Kobe: Economic, Land Use and Housing Perspectives, The Japan Foundation Newsletter, XXVII(1), 13-15,17.

Conference Presentation:

D.W. Edgington (2005) “The Geography of Crisis and Opportunity: Kobe’s Reconstruction Ten Years After the Hanshin Earthquake”, Centre for Japanese Research, UBC, October 28th.