Using Books to Build Bridges Over Troubled Waters: A Curation of Children’s Literature

by Diana Morris

Before beginning her work day, a young teacher turns on the television while making her morning cup of tea. The newscaster is announcing the latest updates for the global refugee crisis. Pictures of terrified children being hoisted out of the water after their boat crashed in an attempt to flee their home country flash across the screen. These children are the same age as her students, yet their realities could not be more different. Her students are being woken up by the sound of alarm clocks, not bombs. Her students will eat a hearty breakfast versus waiting in lines for hours to receive a rationed meal. Her students will be greeted by her smiling face in less than an hour, while children across the world are being forcefully ripped from their families with no idea if they will ever meet again. How can this young teacher begin to teach her students about the crisis the world is facing? How can she educate them about their own privilege while simultaneously building empathy for those whose experiences they cannot begin to fathom? How can she inspire her students to take action and become advocates for global change? These are the questions I ask myself on a regular basis; I am the young teacher.

The global refugee crisis is filled with alarming statics, horrifying photographs, and heartbreaking testimonies. The United Nations reports:

The world is witnessing the highest levels of displacement on record. An unprecedented 70.8 million people around the world have been forced from home by conflict and persecution at the end of 2018. Among them are nearly 30 million refugees, over half of whom are under the age of 18. There are also millions of stateless people, who have been denied a nationality and access to basic rights such as education, healthcare, employment and freedom of movement (n.d.).

In light of this crisis, it is paramount that we educate young people about how and why human displacement occurs, what systems allow for the oppression and displacement of millions of people, what life is like for those who choose or are forced to abandon everything and risk their lives to flee their home countries, and most importantly, how we can support those in need.

In Canada, we are privileged to have a degree of separation from the heart of the displacement crisis, but our obligation to educate remains the same. Through the creation and curation of a personal canon, this paper will explore how children’s literature can be used to help students understand the refugee experience.

♥

My personal inquiry into educating students about the refugee crisis started in 2015, shortly after I finished my teacher education program. Back then, I used a series of newspaper articles, textbook chapters, and Youtube clips to teach students about the large-scale human displacement that was happening around the globe. One fateful day, in 2017, I walked into Kidsbooks in North Vancouver, B.C. and began to share my story with the woman working behind the counter.

“Do I have the book for you!” she exclaimed excitedly, before handing be a copy of Alan Gratz’s Refugee (2017). “This would make a great read aloud for intermediate students.”

I did not know it at the time, but that one small conversation would spark a significant change in my teaching practice. I went home that evening and devoured the book. Quickly, I realized that books were a far more powerful vehicle to engage students and teach them about the world than I had ever given them credit. From that day forward, I began to look for new ways to infuse the Grade 6/7 curriculum with children’s books. I did not throw out my textbooks, articles, and beloved YouTube videos, but rather I began to enhance my practice by incorporating children’s literature.

Refugee tells the stories of three different refugees in three different time periods and locations. Josef is fleeing Nazi Germany with his family, Isabel’s family is desperately trying to find a way out of politically corrupt Cuba, and Mahmoud’s and his family are seeking a way out of Syria as their homeland is ripped apart by war. I used the book as a read aloud with my Grade 6/7 students and my entire class was captivated by the narratives of Josef, Isabel, and Mahmoud who were roughly the same age as they were. Reading the book together with my students allowed me to provide the back-story of Nazi persecution, Fidel Castro’s Communist regime, and the Taliban. Our read aloud became interjected with lessons on history, geography, politics, law, and economics. These lessons weren’t about having students ‘sit down and take notes because there’s a test at the end of the week’; they were about providing context to a story, and were often a result of student questions. As a result of these drop-in lessons, students had a deeper, more meaningful understanding of the topics we were covering in Language Arts, Social Studies, and even Math. I wasn’t interested in my students parroting back the rate of hyperinflation, I wanted them to understand that hyperinflation meant one day a family could buy a loaf of bread and the next day they couldn’t because that same loaf of bread would cost triple the amount or more. Furthermore, I wanted students to appreciate that financial insecurity and corruption is a major factor in many immigrants’ decision to leave their homeland. Instead of having the stereotypical mentality of ‘immigrants are coming to a new country to get rich’, my students were able to appreciate that the conditions in many immigrants’ home countries are unfair and unsustainable, hence moving is one of few viable options to secure one’s future.

In her TEDTalk entitled, Can A Children’s Book Change the World?, Linda Sue Park talks about the power of stories to ignite empathy and engagement. Park states:

Through the characters I came to love, I practiced facing unfairness with, bitterness and anger sometimes, but also with hope, with righteous anger, with determination. I wasn’t taught these remarkable truths, I learned them by being immersed in story. Not lessons that would be forgotten, but stories that become a part of me. (2018)

I cannot say for sure whether my students loved Josef, Isabel, and Mahmoud, but they certainly felt passionate about their plight and wanted to do something about it. Even though the characters were fictionalized, their narratives become a part of my students’ worldview. Together, my students and I created a ‘re-education’ campaign to combat typical stereotypes one hears about immigrants and refugees. My students created posters to put up around the school and visited younger classrooms to share their learning. If I were to do this unit again, I would like to incorporate a wider variety of children’s literature as a way to delve deeper into the themes, and to bring new perspectives into the classroom. It would also be nice for my older students to bring picture books to read with younger students so they could engage in conversations with their ‘little buddies’.

In the spirit of reflection and development as an educator, I have created a personal canon that I would use in the future to teach students about the refugee experience. Below you will find a wide variety of books that could be used to deepen understanding and empathy in an upper intermediate classroom. I have organized the collection using a series of essential questions, followed by some of my favourite picture books, short stories, youth fiction and young adult novels. I have also included some titles for pre-teaching, supplementing, extension, or enrichment. I have curated each section with research and personal suggestions for how I would use the books in my own classroom. However, these are only suggestions and I encourage and welcome new approaches. I hope you find the collection inspiring, practical, useful or whatever you need it to be in your own journey as an educator.

♥

“Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” – Nelson Mandela

♥

• How does the refugee experience impact and shape one’s identity?

Identity is a powerful concept that is evident throughout the redesigned B.C. Curriculum. In 2018, literacy guru, Adrienne Gear, released her latest book Powerful Understanding. The entire first section of the book is dedicated to ‘understanding self’, and in it, one will find a fabulous lesson entitled ‘The Story of My Name’. This past year, I did a one-off lesson where I had students go home and ask their parents/guardians about the story behind their name. In our morning meeting, students each shared what they learned and we moved on with our day.

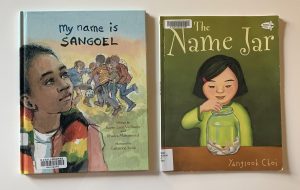

Through the development of this personal canon, I have been reflecting back on that lesson and the opportunity I had to integrate some fabulous picture books to enhance student understanding. Given another chance, I would love to go further with the concept of identity and the power of one’s name and relate it to the refugee and/or immigrant experience. My Name is Not Refugee, My Name is Sangoel, and The Name Jar are three fabulous reads that would allow for students to reflect on how important names are to one’s identity and sense of belonging.

• To what extent can friendship alter the refugee experience?

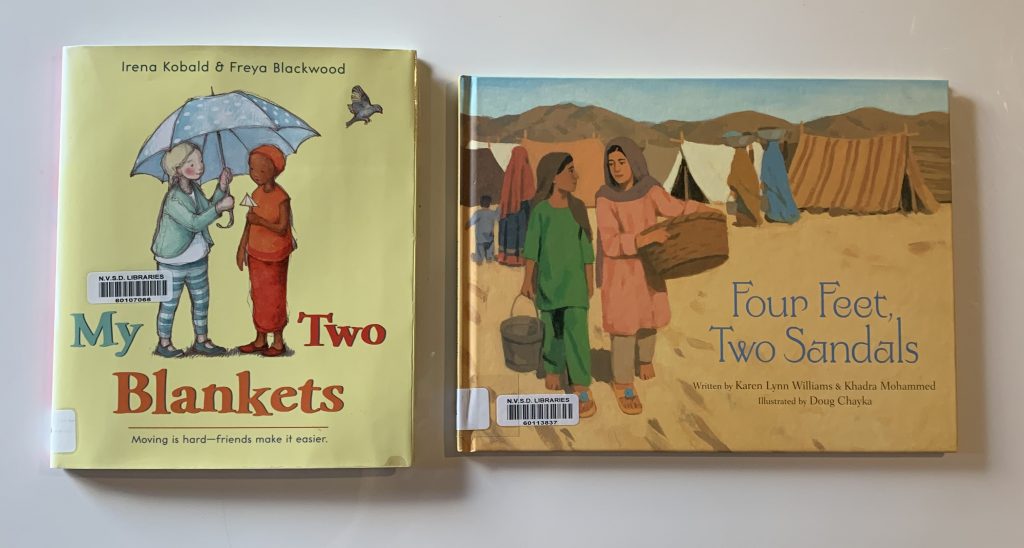

Friendship is another powerful concept that is often at the heart of pre-teens’ lives. Their worlds revolve around their friends, and adolescents can often relate to feelings of social isolation and loneliness. To capitalize on this understanding, I thought it was fitting to explore the value of friendship in relation to the refugee experience. My Two Blankets and Four Feet, Two Sandals are two touching stories about the power of friendship and how a single person can alter an experience for the better.

• To what extent is war a catalyst for human displacement?

When creating my personal canon, I knew it had to include some element of warfare. You see, I was always that kid who wanted to know more about why countries fought against each other. My dad and grandfather were both history buffs, so naturally, I went on to study history for my undergraduate degree. A major part of my teaching philosophy is being passionate about what I teach. Passion ignites passion.

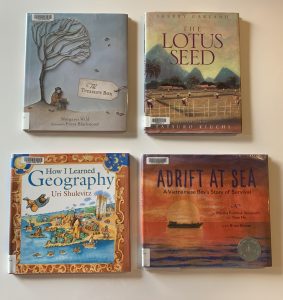

Now that I am a teacher, I find that many students share the same fascination for warfare I had when I was a student. Pictured below are four great reads that could open up conversation about conflict and the resulting displacement of people.

How I Learned Geography and Adrift at Sea are both based on true stories and childhood memories of the authors. It would be interesting for students to look at how memory shapes a narrative, and how trauma can become a catalyst for creative outlets, such as writing a book.

• How can poetry be used to capture the refugee experience?

Robert Frost defined poetry as the shortest emotional distance between two points. Poetry has a timeless quality to connect to the human experience that is relatable to the masses. As poetry is left for interpretation, it can be taken up by a variety of audiences. As Ciara Murphy (2015) notes, adolescents in particular seem to relate to poetry. As a result, poetry has become commonplace in YA literature.

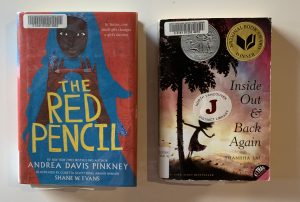

Both The Red Pencil and Inside Out & Back Again are entirely written in verse. Similar to other ‘alternative’ publication formats, verse gets student thinking about the different forms of text. All of a sudden they have to pay closer attention to the vocabulary being used, the placement of words on the page, even the spaces are important! As teachers, we need to strengthen students’ abilities to read beyond the words. Both of these books would be fabulous additions to any classroom.

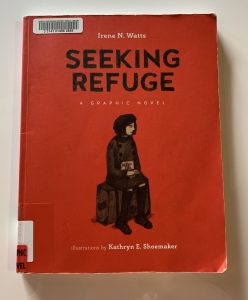

• How can graphic novels be used to capture the refugee experience?

Some people might shy away from using graphic novels for serious topics such as warfare, displacement, and the refugee experience. However, with the popularity and proliferation of graphic novels it would be a shame not to incorporate them into a personal canon. Graphic novels encode huge amounts of information into pictures with minimal amounts of text. Readers have to be strategic at unpacking what they see to make sense of the narrative.

Fasbender, Dulaney, and Pope (2013) highlight the educational and literary value of graphic novels for young readers, but also remind educators that “we cannot rely solely on works from the past to teach the present and the future (p. 24).”

As teachers, we must move away from including books in the canon simply because they have “stood the test of time”; when we distance ourselves from that criterion, we make room for books that both engage and challenge students. History alone should not determine which books we include in the canon or curriculum. We should instead consider how teachable and relevant the texts and learning opportunities are for contemporary students. It is these criteria that will strengthen students’ engagement in the language arts classroom and increase their willingness to invest more time in the literature they find provocative and valuable. (Fasbender, Dulaney, and Pope, 2013, p. 23)

Graphic novels are some of the post popular books in our school’s library. Keeping this mind it was integral to include graphic novels in my literary canon. I also think it’s important that a person canon includes ‘something for everyone’. If we want students to read great books, we need to make sure they enjoy what they’re reading,

• What is the relationship between illustrations and the refugee narrative?

Integrating children’s literature with the arts provides new pathways for learning. When children are invited to explore the images, thinking about their creation, intent, and impact, they are building richer literary skills and strategies.

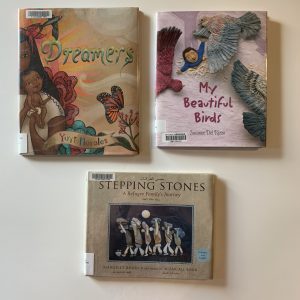

Additionally, these books could be used to inspire art lessons where children could take up a new method, medium or process for the creation of their artwork. Stepping Stones uses rock formations to tell a story, whereas My Beautiful Birds is photographed felt. Both mediums are a far cry from the typical felt pens, pencil crayons and water colours that are usually used in classrooms.

All three stories include a message from the artist which could be used to enhance students’ understanding about the relationship between illustration and narrative. Leland, Lewison, and Harste (2012) emphasize that the integration of visual arts and literature give students “new way[s] of enjoying, digging deeper and talking back to books (p.129).”

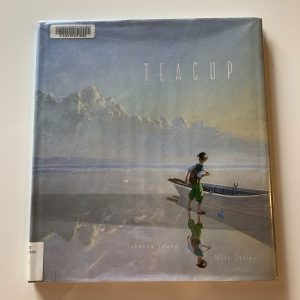

• How can wordless books be used to capture the refugee experience?

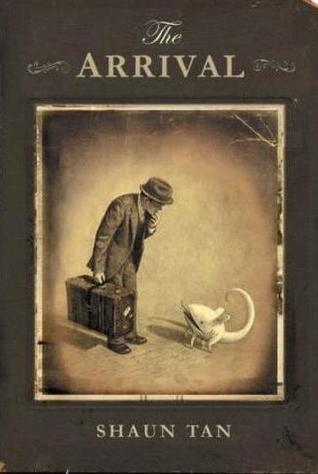

While not necessarily about a refugee, Shaun Tan’s wordless book The Arrival does an outstanding job at portraying the immigrant experience. The intentionality within each frame of Tan’s book is remarkable. Because the narrative is not explicitly told to students in words, there is room for interpretation and various perspectives. Students have to become masters at inferencing to create the story for themselves.

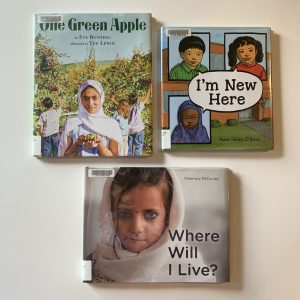

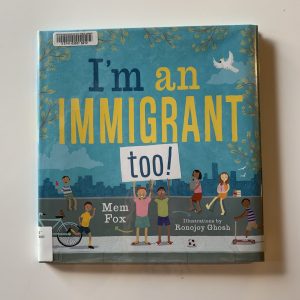

• What books can be used with emergent readers and/or complex students to learn about the refugee experience?

Teaching mature topics such as the refugee experience can be difficult when it comes to emergent readers and complex learners. However, difficult does not mean impossible. The three titles pictured above are all wonderful examples of picture books that are accessible to a wide variety of students, with varying reading abilities and comprehension levels. Where Will I Live, in particular, is a great book that I would read to all students in my class. The words are simple, but when coupled with the photographs they tell a deeply profound story. There are so many examples of picture books that have access points for everyone in the classroom.

♥

• Picture Books

Picture books are essential to any literary canon, even in the intermediate classroom. “As metaphoric spaces, picture books allow learners to explore complex social themes and ideas by creating pathways that permit playful and authentic exploration.” (Forbes-Rolfe, 2015, p.35)

When reading a picture book the reader is having to do more than just read the words on the page. A good reader will also read the pictures, which provides a whole new layer to the experience. A good reader will make connections between pages and ask critical questions about how the author is conveying meaning. Picture books often play with typeface and layout, all of which good readers will learn to evaluate in their interpretation of the story. Just as important as it is for students to read picture books, teachers need to model how to read pictures books well.

• Short Stories

I love reading short stories in the classroom. In my experience, students love them too. There is something inherently satisfying about getting through an entire story in one sitting. Both of the following books contain a series of short stories of refugee children that are jam-packed with emotion; a box of tissues is strongly recommended! The messages of hope, resilience, perseverance and determination are astounding and truly inspirational to youth and adults alike.

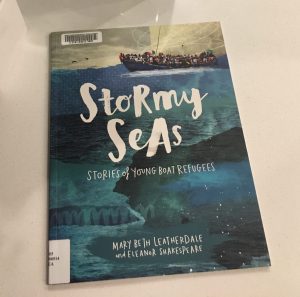

Stormy Seas: Stories of Young Boat Refugees is written in an infographic style that highlights personal memoirs of young refugees from all over the world. From Nazi Germany to war ravaged Vietnam, this book captures the power of the human spirit while educating readers with powerful statistics, side bars, and factoids. Furthermore, Stormy Seas is a great example of a non-fiction text that gives students an entry point into another set of skills. Young, Moss and Cornell (2007) highlight the importance of teachers integrating non-fiction books into their collections for a number of reasons. According to their research, non fiction texts help spark student curiosity and create a sense of wonder, promote lines of inquiry, build and enrich vocabulary, develop critical thinking skills, and promote informational literacy skills and reading strategies. Furthermore, the visual format of non-fiction texts may entice a different type of reader than the traditional chapter book.

Stormy Seas: Stories of Young Boat Refugees is written in an infographic style that highlights personal memoirs of young refugees from all over the world. From Nazi Germany to war ravaged Vietnam, this book captures the power of the human spirit while educating readers with powerful statistics, side bars, and factoids. Furthermore, Stormy Seas is a great example of a non-fiction text that gives students an entry point into another set of skills. Young, Moss and Cornell (2007) highlight the importance of teachers integrating non-fiction books into their collections for a number of reasons. According to their research, non fiction texts help spark student curiosity and create a sense of wonder, promote lines of inquiry, build and enrich vocabulary, develop critical thinking skills, and promote informational literacy skills and reading strategies. Furthermore, the visual format of non-fiction texts may entice a different type of reader than the traditional chapter book.

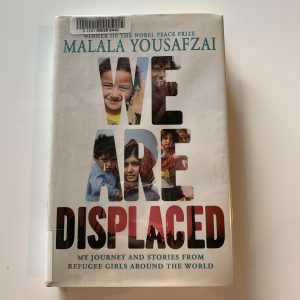

We are Displaced: My Journey and Stories from Refugee Girls Around the World is written in the traditional chapter book style and would be a great extension to Stormy Seas.

We are Displaced: My Journey and Stories from Refugee Girls Around the World is written in the traditional chapter book style and would be a great extension to Stormy Seas.

“What tends to get lost in the current refugee crisis is the humanity behind the statistics (Yousafzai, 2018).” We Are Displaced seeks to re-humanize the refugee experience by sharing personal accounts from inspiring young girls who are not defined by their experience. This book also promotes reading as a form of activism; proceeds from the sales of this book go towards Malala’s charity.

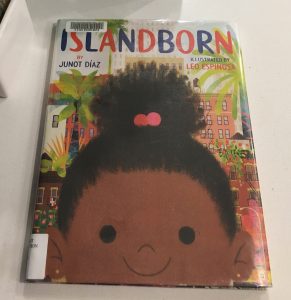

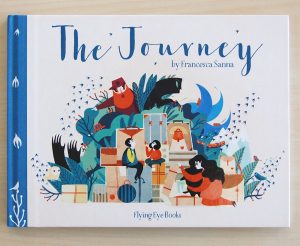

• Youth Fiction

These ‘junior’ novels are both captivating reads that are sure to pique the interest of even your most reluctant readers. These titles could be used as quick read alouds or novel studies. They would also be great additions to a literature circle set for lower level readers, English Language Learners, or reluctant readers. Both stories are fast-paced and straight-forward. With the diverse needs of readers in our classroom, it is essential that we fill our classroom libraries with books for everyone.

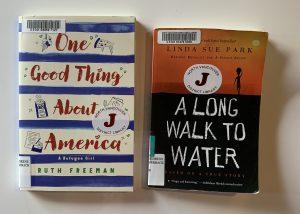

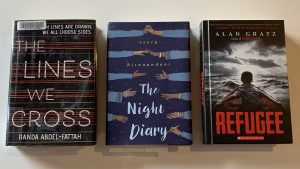

• Young Adult Novels

The novels pictured above could be used as read alouds in an upper intermediate classroom, or could be incorporated into literature circles. They are definitely more mature reads and, at times, the content can be quite heavy. All four titles are historical fiction, so being able to front load students with information about the historical context in which these stories take place may be beneficial to their overall understanding and appreciation of the narratives.

♥

Great Books for ‘Pre-Teaching’ or Supplementing the Unit

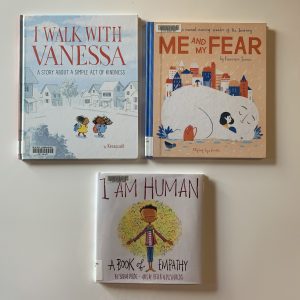

• I Walk with Vanessa is a lovely wordless picture book that captures the beauty of one small act of kindness. Students use inferencing skills to ‘read the pictures’ and create their own narrative. In short, the book is about a girl who witnesses another girl getting picked on on their way home from school. The bystander is troubled by the event and goes home to mull over the fact that she didn’t do anything. In the night, an idea comes to her and she transitions from bystander to ally.

• Me and My Fear is about the characterization of fear (Fear becomes a character) and how fear and anxiety interfere with daily life. The book specifically tackles how fear is acutely felt by newcomers as they attempt to navigate life in a new school, new community, new country. In the book, ‘Fear’ follows a student who has recently immigrated; Fear is always nearby, when she plays, eats, goes to school. As the student becomes more comfortable with her environment, Fear shrinks. Soon she realizes that everyone carries Fear with them, sometimes it’s just harder to see. A great book to use to open up discussions about the ubiquitous nature of fear and anxiety, and strategies for coping with these emotions.

• I am Human is a great story about the experiences that unite all human beings. It delves into human behaviour both on an individual and global scale. The story reminds us that we are all more alike than we are different. Once we appreciate ourselves for who we are (flaws and all), we learn how to accept and appreciate others.

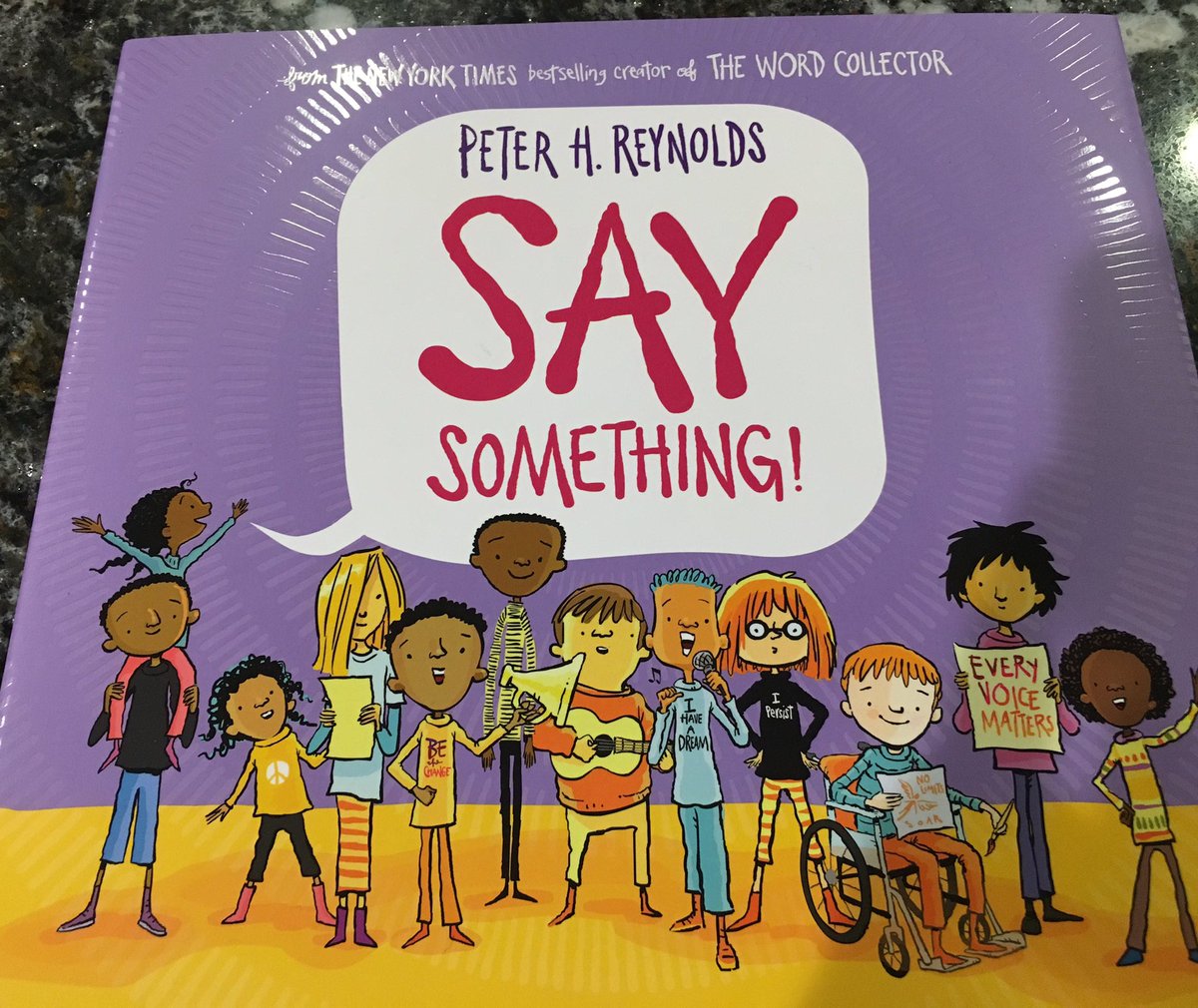

• Say Something is yet another brilliant book by Peter H. Reynolds. This books serves as a call to action for children and youth to speak out against injustice. It reminds readers about the power of their voice to make the world a better place. A must read for any teacher promoting social activism.

♥

More Titles for Extension, Enrichment, or Interested Students

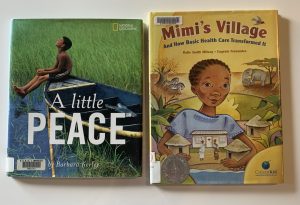

Here are some great picture books about life in developing countries. A Little Peace follows a similar photo-journalism narrative style as Where Will I Live? The book reminds us that small acts of kindness help create peaceful communities.

Here are some great picture books about life in developing countries. A Little Peace follows a similar photo-journalism narrative style as Where Will I Live? The book reminds us that small acts of kindness help create peaceful communities.

Mimi’s Village: And How Basic Health Care Transformed It is a great entry point for students to understand how access to health care can transform a community. Something we take for granted can be the difference between life and death on the other side of the world. The author of Mimi’s Village also wrote One Hen: How Small Loan Made a Big Difference which explores micro-finance and the impact it has on developing communities, and The Good Garden: How One Family Went from Hunger to Having Enough which looks at how food security can be supported through sustainable farming and gardening.

♥

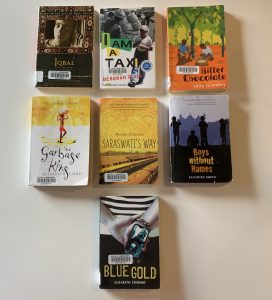

Here are some other novels that I have used in my Grade 6/7 classroom. While not explicitly about refugees, these books would allow students to understand the push/pull factors that influence people to immigrate. These books are great for captivating student interest, while teaching them about poverty and overcoming adversity in developing countries. These are great titles for literature circles as they can be easily differentiated, and are related to the Grade 6/7 curriculum.

Here are some other novels that I have used in my Grade 6/7 classroom. While not explicitly about refugees, these books would allow students to understand the push/pull factors that influence people to immigrate. These books are great for captivating student interest, while teaching them about poverty and overcoming adversity in developing countries. These are great titles for literature circles as they can be easily differentiated, and are related to the Grade 6/7 curriculum.

♥

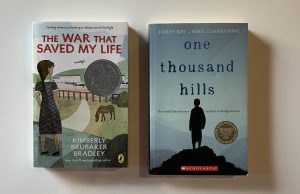

These two books would be great extensions for students who are interested in the relationship between warfare  and the displacement of peoples.

and the displacement of peoples.

How the War Saved my Life is about an overprotected disabled girl who is sent to the British countryside with her brother during The Blitz. While there, she experiences a new kind of freedom that changes her life forever.

One Thousand Hills is fictionalized memoir about a young boy’s journey through the Rwandan genocide. This story explores the power of family and faith when it comes to survival.

♥

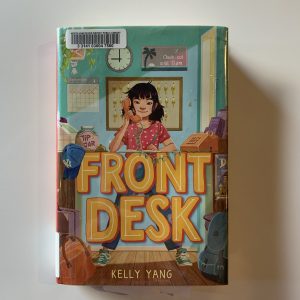

A great read for students who are interested in learning more about the immigrant experience and how families navigate the immersion into a drastically different environment.

A great read for students who are interested in learning more about the immigrant experience and how families navigate the immersion into a drastically different environment.

Front Desk is about a Chinese family who immigrates to the U.S. and takes over the running of a hotel. The kids were under the impression that the U.S. was the land of freedom and endless hamburgers… in reality, the U.S. turns out to be a difficult place to navigate for newcomers. While lighthearted and funny, this book explores big topics such as immigration, poverty, racism, fraud and bullying.

♥

Referenced Works:

Abdel-Fattah, R. (2017). The lines we cross. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Bradley, K.B. (2015). The war that saved my life. New York, NY: Puffin Books.

Bunting, E., & Lewin, T. (2006). One green apple. New York, NY: Clarion Books.

Choi, Y. (2001). The Name Jar. New York, NY: Dragonfly Books.

D’Adamo, F., & Leonori, A. (2001). Iqbal. New York, NY: Aladdin Paperbacks.

Del Rizzo, S. (2017). My beautiful birds. Toronto, ON: Pajama Press Inc.

Diaz, J., & Espinosa, L. (2018). Islandborn. New York, NY: Dial Books.

Ellis, D. (2006). I am a taxi. Toronto, ON: Groundwood Books.

Fassbender, W. J., Dulaney, M., Pope, C. A (2013). Graphic narratives and the evolution of the canon: Adapting literature for a new generation. Voices from the Middle, 21(1), 19

Forbes-Rolfe, J., Kaczmarska, M., & Hinman, J. (2015). A meditation on the good old picture book. Ethos, 23(1), 36-37.

Forchuk Skrypuch, M., Ho, T., & Deines B. (2016). Adrift at sea: A Vietnamese boy’s story of survival. Toronto, ON: Pajama Press Inc.

Fox, M. (2017). I’m an immigrant too. New York, NY: Beach Lane Books.

Freeman, R. (2017). One good thing about America: A refugee girl. New York, NY: Holiday House.

Furman, R., Langer, C. L., Davis, C. S., Gallardo, H. P., & Kulkarni, S. (2007). Expressive, research and reflective poetry as qualitative inquiry: a study of adolescent identity. Qualitative Research, 7(3), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794107078511.

Garland, S., & Kiuchi, T. (1993). The lotus seed. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Punlishers.

Gear, A. (2018). Powerful understanding. Vancouver, BC: Pembroke Publishers.

George, A.M., & Swan, O (2016). Out. Toronto, ON: Scholastic Canada.

Gratz, A. (2017). Refugee. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Grindley, S. (2010). Bitter chocolate. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

Hiranandani, V. (2018). The night diary. New York, NY: Dial Books for Young Readers.

Kerascoët (2018). I walk with Vanessa. New York, NY: Schwartz & Wade Books.

Kerley, B. (2007). A little peace. Washington, DC: National Geographic.

Kobald, I., & Blackwood, F. (2014). My two blankets. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Kullab, S., & Roche, J. (2017). Escape from Syria. Toronto, ON: Firefly Books.

Lai, T. (2011). Inside out & back again. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Laird, E. (2003). The garbage king. London, UK: MacMillan’s Children’s Books.

Leatherdale, M.B., & Shakespeare, E. (2017). Stormy seas. Toronto, ON: Annick Press.

Leland, C., Lewison, M., & Harste, J. (2012). Multimodal responses to literature. In Teaching children’s literature: It’s critical. Taylor andFrancis, p. 125-236.

McCarney, R. (2017). Where will I live? Toronto, ON: Second Story Press.

Milner, K. (2017). My name is not refugee. Edinburgh, UK: Bucket List Books.

Morales, Y. (2018). Dreamers. New York, NY: Neal Porter Books.

Murphy, C. (2015, October 5). Why is there so much poetry in YA/teen lit? Retrieved July 25, 2019, from http://www.theguardian.com/childrens-books-site/2015/oct/05/poetry-in-ya-teen-lit-john-green

O’Brien, A.S. (2015). I’m new here. Watertown, MA: Charlesbridge.

Park, L. (2010). A long walk to water. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Park, L. (2018). Can A Children’s Book Change the World? | Linda Sue Park | TEDxBeaconStreet. [online] YouTube. Available at: Can A Children’s Book Change the World? | Linda Sue Park | TEDxBeaconStreet

Pinkney, A.D., & Evans, S.W. (2014). The red pencil. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company.

Province of British Columbia. (2016). BC’s new curriculum. Retrieved from: https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/

Reynolds, P. (2019). Say something. New York, NY: Orchard Books.

Roy, J., & Zihabamwe, N. (2016). One thousand hills. Toronto, ON: Scholastic Canada.

Ruurs, M., & Ali Badr, N. (2016). Stepping stones: A refugee family’s journey. Victoria, BC: Orca Books Publishers.

Sanna, F. (2016). The journey. London, UK: Flying Eye Books.

Sanna, F. (2018). Me and my fear. London, UK: Flying Eye Books.

Schröder, M. (2010). Saraswati’s way. New York, NY: Square Fish.

Sheth, K. (2010). Boys without names. New York, NY: Balzer & Bray.

Shulevitz, U. (2008). How I learned geography. New York, NY: Farrar Straus Giroux.

Smith Milway, K., & Fernandes, E. (2012). Mimi’s village: And how basic health care transformed it. Toronto, ON: Kids Can Press.

Stewart, E. (2014). Blue gold. Toronto, ON: Annick Press.

Tan, S. (2006). The arrival. Sydney, NSW: Hodder & Stoughton.

United Nations (n.d.). Refugees. Retrieved July 16, 2019, from https://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-depth/refugees/

Verde, S., Reynolds, P.H. (2018). I am human: A book of empathy. New York, NY: Abrams the Art Books.

Watts, I., & Shoemaker, K. (2016). Seeking refuge. Vancouver, BC: Tradewind Books.

Wild, M., & Blackwood, F. (2013). The treasure box. Sommerville, MA: Candlewick Press.

Williams, K.L., Mohammed, K., & Stock, C. (2009). My name is Sangoel. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Books for Young Readers.

Williams, K.L., Mohammed K., & Chayka, D. (2007). Four feet, two sandals. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Books for Young Readers.

Williams, M. (2011). Now is the time for running. London, UK: Little, Brown and Company.

Yang, K. (2018). Front desk. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Young, R., & Ottley, M. (2015). Teacup. New York, NY: Dial Books for Young Readers.

Young, T. A.,Moss, B., & Cornwell, L. (2007). The classroom library: A place for nonfiction, nonfiction in its place. Reading Horizons, 48(1), 1-18. Retrieved from http://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1071&context=reading_horizons.

Yousafzai, M. (2018). Malala Fund. Retrieved on July 25, 2019, from: https://www.malala.org/newsroom/we-are-displaced-out-now

Yousafzai, M. (2019). We are displaced: My journey and stories from refugee girls around the world. London, UK: Little, Brown and Company.

♥