Customary Tenure Systems and Territorial Rights. Speaking notes for CICADA axis presentation.

Jun 22nd, 2018 by cmenzies

June 18, 2018. Unceded Indigenous lands of the Kanien’kehá:ka Nation

Tiohtiá:ke/Montreal.

Tenure and territorial rights are fundamental material conditions for all societies.

Our focus on Indigenous communities necessitates examination of colonial processes, which quite bluntly are capitalist processes pure and simple. By this I mean that for the last several centuries the underlying fundamental driver of global and regional economies has been the capitalist mode of production. Colonialism, the notion of one nation (or similar group) occupying the territories of another, has been and continues to be, an intrinsic part of the mechanisms of the capitalist mode of production. I would argue, and submit that the material evidence supports this contention, that there is no colonialism separate from capitalism in the context of today’s indigenous peoples.

Tenure: notions of property – control/transmission, use, access – authority and jurisdiction. Tenure here can be thought of a process of property making – in the sense that these are the social and cultural rules whereby people structure relations to land and water domains. Within many kin ordered societies landed property is not alienable from the rights/property holding group. One of the key features of the capitalist system has been the attempts to transform property into an alienable commodity that is severed from relations with social groups. Comparative studies of this process and Indigenous responses would be a productive avenue to explore through this axis.

Territorial Rights – extent to which rights extend geographically. It would seem that scaling up in an additive sense from social holdings of kin groups leads directly to the territorial extent of an Indigenous people. But here is another key domain wherein the expansion of capitalist relations of production and the accompanying colonization of Indigenous territories have transformed any simply extension of tenure to territory within Indigenous communities. The intrusion of capitalist relations of production, combined with the superstructural legal frameworks criminalizing Indigenous practices, has had a profound effect on re-spatializing Indigenous territories in ways that blend customary with capitalist perceptions of territories. This has led to conflicts within and between Indigenous peoples and between the encapsulating colonial nation states and Indigenous polities.

Anthropological research on indigenous tenure and territorial rights has tended toward an ahistorical approach. This is not to say that history is not considered, but it is typically framed as a history of encroachment of the settler into the Indigenous spaces (history is indeed some part encroachment) in which Indigenous spaces and practices are resented as timeless essentialized entities. Much such anthropological work proceeds by interviewing contemporary community, constructing a model of what was, and then asserting that this is the way it always has been (even as noting the encroachment of colonialism).

There is a flip side to this – the colonialist narrative that suggests there has been so much change that the discontinuity renders contemporary Indigenous survivors alienated from our pasts in ways that, legally at least, dispossess us from our ancestral rights and title. Both of these naïve views are problematic and require turning a blind eye to empirical evidence that complicates the production of easy narratives.

Let’s consider an example from the north coast of BC. Three first nations: Haisla, Allied Tsimshian Tribes, and Gitxaała (for a more detailed treatment see People of the Saltwater, 2016). Each nation experienced the insinuation of capitalism into their shared regional economies similarly. However, the local outcomes and implications varied in accord with local specificities.

Haisla: This was a region initially ignored by capitalist extraction in significant ways until the mid twentieth century. Haisla community members participated as labourers in the forest and fisheries industries, but capitalism’s major foray into this region was with the establishment of a aluminum smelter that took advantage of cheap hydro electric power to transform Australian bauxite into aluminum for manufacture into commodities produced elsewhere.

Allied Tsimshian Tribes – their main economic territories were salmon rich tributaries along the Skeena River. Here they found themselves in direct competition with the capitalist salmon canning industry. Drawing upon the legal exclusions that pre-empted the commercial rights of the Allied Tribes, they found them selves displaced from their traditional territories that had been the economic backbone of their chiefly economy. As a consequence they become integrated into the industrial commercial fishery at a high level. This had implications for the functioning of their internal political system as at the same time as the economic power base to the chiefly classes was being undercut the original ten individual village polities that pre-existed Allied Tribes collapsed as political entities and the people coalesced around the Hudson Bay trading post at Fort Simpson.

Gitxaała amongst all the Tsimshianic villages was the only one to not face a displacement out of their territory. The chiefly class in Gitxaała had their territories based around coastal sockeye creeks. These were smaller, less productive (in comparison to the Skeena River) and thus of less interest to the capitalist canners. Here Gitxaała chiefs maintained formal and economic control over these sites as productive fisheries until well into the 1960s. Unlike the other chiefly groups (who lost their economic base, in terms of the Allied Tsimshian Tribes or had an economic base that wasn’t valourized under capitalism, in terms of the Haisla) Gitxaała’s chiefs maintained their economic power in tandem with their customary authority.

In each of this cases similar notions of tenure and territoriality existed at the commencement of the colonial period, yet the ways in which the insinuation of capitalism into this region occurred was shaped by the micro-specificities of each case.

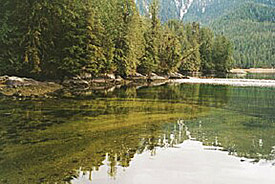

we knew the lake was frozen, but not enough to walk over. There was lots of open water along the creek mouth shoreline where we would have previously put our rafts in to paddle the 1.5 km length of the lake to the next trail head.

we knew the lake was frozen, but not enough to walk over. There was lots of open water along the creek mouth shoreline where we would have previously put our rafts in to paddle the 1.5 km length of the lake to the next trail head.