Written for University of Toronto Archives and Records Management System

Eva-Marie Kröller and John Barker

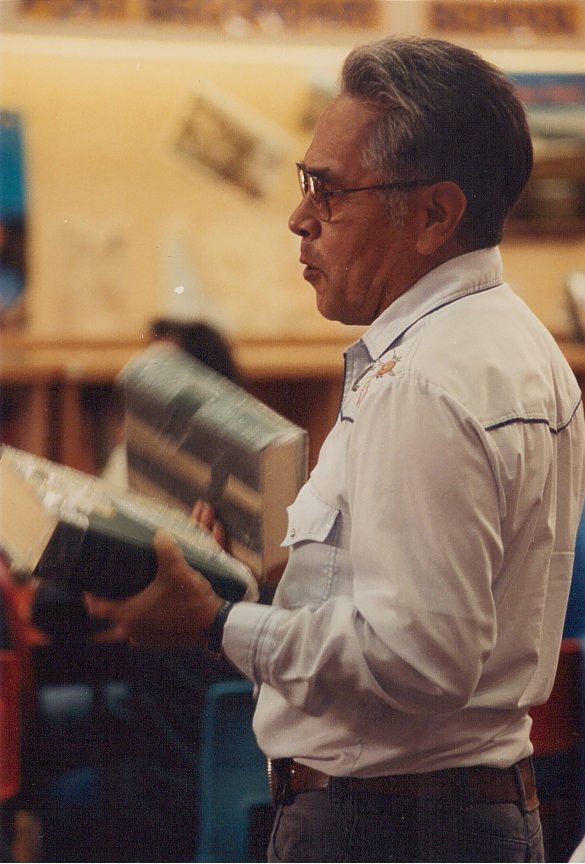

A photo of Hereditary Chief Lawrence Pootlass (Nuximlayc)

Eva-Marie Kröller

Among the illustrations I collected for Writing the Empire: The McIlwraiths, 1853-1948 was a collage of photos. They had been taken at the potlatch held in Bella Coola just before the publication, in 1992, of the second edition of T.F. McIlwraith’s The Bella Coola Indians (UTP), originally published in 1948. I came to know these images very well because the sheet containing them was so large that it had to sit on top of the files and so displayed the photos every time I opened the box. The image that gradually occupied me the most was a snapshot of hereditary chief Lawrence Pootlass (Nuximlayc) holding the two volumes of the 1948 edition, tattered and patched from frequent use. He was addressing his community, McIlwraith’s family, and editor John Barker, all of whom had been invited to honour T.F.’s memory and “his work among [the Nuxalk] nearly seventy years earlier.” Endorsements from Pootlass also preface both the second edition of The Bella Coola Indians and the collection, edited by Barker and Douglas Cole, of McIlwraith’s field letters (2003). As several reviewers have insisted, including Jacinda Mack (Nusqumata), McIlwraith’s hosts were his research partners who – according to Radio Nuxalk inviting listeners to share their thoughts about the anthropologist earlier this summer – endeavoured to “teach and prepare McIlwraith for the knowledge he was allowed to save for future generations.” An audio book, Ya Wa Smsmalh Ts (Our Good Stories), was also presented on Radio Nuxalk, including readings from The Bella Coola Indians. The scene echoes the evenings on which McIlwraith’s research partner Jim Pollard had his granddaughter read to him from the book when it first appeared. Together with Nuxalk hospitality and appreciation, the photo of Lawrence Pootlass encapsulates his community’s self-confidence and pride.

As I worked through the letters documenting T.F. McIlwraith’s adolescence, army days, and studies at Cambridge, the meaning of “education” became increasingly complex. The months he spent at Bella Coola introduced a sharp break from the entitled imperialism informing his early upbringing, a development that speaks to the careful teaching he received from the Nuxalk and his readiness to receive it. A second break reinforced the first. The manuscript of McIlwraith’s research on the Nuxalk was completed in 1927 but censorship and other reasons discussed by Barker and Barnett Richling delayed publication until 1948. The intervening years brought the rise of fascism and the Second World War and confronted McIlwraith with the consequences of the racial theories that underpinned his anthropological studies at Cambridge. Some of these ideas linger in his book, left essentially in its 1927 version, and he had much more to learn, but he was alerted for good to the disastrous and global consequences of racism. At a symposium, organized with C.T. Loram from Yale University and opened three days after the Second World War began, Indigenous delegates expressed their thanks for the invitation and assured their “white brothers” that they intended to return the favour for any gathering they might themselves call in the future, “for the purpose of finding solutions to the white man’s dilemma in a social and economic order that has, during the past decade, gone on the rocks.”

Like his teacher A.C. Haddon in his book with Julian S. Huxley (1935), McIlwraith began to combat racism in the public wherever he found it, whether it be the disrespectful treatment of Indigenous veterans or the prejudicial depiction of history in historical pageants and fiction. Thus he angrily informed the author Mabel Burkholder that her views of Native people in the Hamilton region were altogether wrong, and he requested that the post-war organizers of the Brébeuf pageant at Martyrs’ Shrine in Midland, Ontario demonstrate respect in their depiction of the Iroquois.

Jacinda Mack (Nusqumata) has called McIlwraith’s research an “important instrument of reclamation.” In vivid illustration of “books have their fates,” The Bella Coola Indians and the field letters describing its genesis are not only foundational and collective research but have become part of a living culture.

On Authorship of The Bella Coola Indians

John Barker

In the summer of 1990, I was approached by a Vancouver dealer in antiquarian books. He had learned of my interest in TF McIlwraith and was able to offer me The Bella Coola Indians for $900. I was sorely tempted, but the price was way beyond my paltry assistant professor salary. Yet the event lit a fuse. I had been using one of the two copies of the work at the UBC Library. Both were in wretched shape: whole sections had been cut out and replaced with pasted-in photocopies. I was troubled that such a significant work, having narrowly escaped the claws of Ottawa censors in the first place, appeared to be destined for the Rare Books room, available only to the most determined researchers. So, I initiated a campaign to save it, enlisting a score or so of academics to bombard the University of Toronto Press with letters in support of reprinting or creating a new edition of the BCI. After the Press expressed wary interest, I made arrangements to visit Bella Coola. A new publication of the BCI and theform it might take hinged on the approval of the Nuxalk Nation.

At the time, I knew Bella Coola only from McIlwraith’s unpublished letters and Harlan Smith’s photographs. It was much changed, of course, but I recognized several landmarks and was thrilled to be there. I soon learned that several families had treasured copies of the BCI secreted in their houses. A battered set, held by Chief Pootlass in the photograph above, was stored in the Band safe. I was curious to learn what people remembered about McIlwraith’s visits. It turned out they recalled very little. Instead, the elders wanted to talk about Jim Pollard, Captain Schooner and other elders who had contributed so much to the BCI. My hosts arranged a meeting of Nuxalk elders. Conversing in the Nuxalk language, they enthusiastically approved the project. I then asked my next make or break question: did they want a reprint or a new edition? McIlwraith had a poor grasp of Nuxalk, translating material instead from the simpler Chinook Jargon. Further, in the long journey of the manuscript, he had re-edited most of the stories several times, in some cases translating long passages into Latin and then back into English. It was their call, but I knew that editing the work would probably sink the project. They insisted on a reprint. “These are the words of our grandparents,” they said. “They must be respected.”

I write this story to point to a common but significant ambiguity in anthropological publications. All ethnographies are collaborative, born out of conversations, the results effectively multi-authored. Yet they typically appear as the single-authored work of the anthropologist. The Nuxalk elders appreciated the work McIlwraith carried out, but they were absolutely clear about who the authors of the BCI were. I was impressed by their firmness and clarity, which inspired the opening sentence of my Introduction to the reprint: “Ethnographies begin as conversations between anthropologists and their hosts…if you listen closely, you almost hear the voices.” This seemed commonsensical, so it came as a surprise when the reviews came out and my words were praised and/or criticized as laying a “postcolonial” framework on a classic work.

It is obvious from his fieldwork letters, that McIlwraith was perfectly aware of, indeed reveled in, a rewarding collaboration with his Nuxalk friends and adopted family. A shift happens in his extended correspondence with his tormentors at the National Museum in which he describes the BCI as an objective “scientific” work. He makes clear in the painful final pages of the BCI that he expected the Nuxalk culture, if not the people, to be “blotted out” by “White civilization” and made no effort to return. I wonder if he knew of the 42 sets purchased by Nuxalk from the Kopas general store in the late 1940s at the then steep price of $30, an early act of repatriation. I expect he would have been delighted to know that the reclaimed work became a vital resource in the revitalization of Nuxalk traditions, alongside the vibrant memory culture maintained by the elders. Watching his son, Tom, decorated and dancing at the Pootlass-Brown potlatch in 1992, I felt the smiling presence of his father.

In one of the less friendly reviews of my Introduction, I was criticized for writing so little about McIlwraith’s family background. This deficient has now been addressed by Eva-Marie Kröller’s brilliant Writing the Empire: The McIlwraiths, 1853-1948. The entertaining liveliness of McIlwraith’s letters and the fluency of his analysis of Nuxalk spirituality and social organization did not arise sui generis; they too were multi-authored.