Written for the archivists of Weston Corporate Archives and of the Archives et bibliothèque nationales du Québec, and with special thanks to André Lamontagne

May 2022

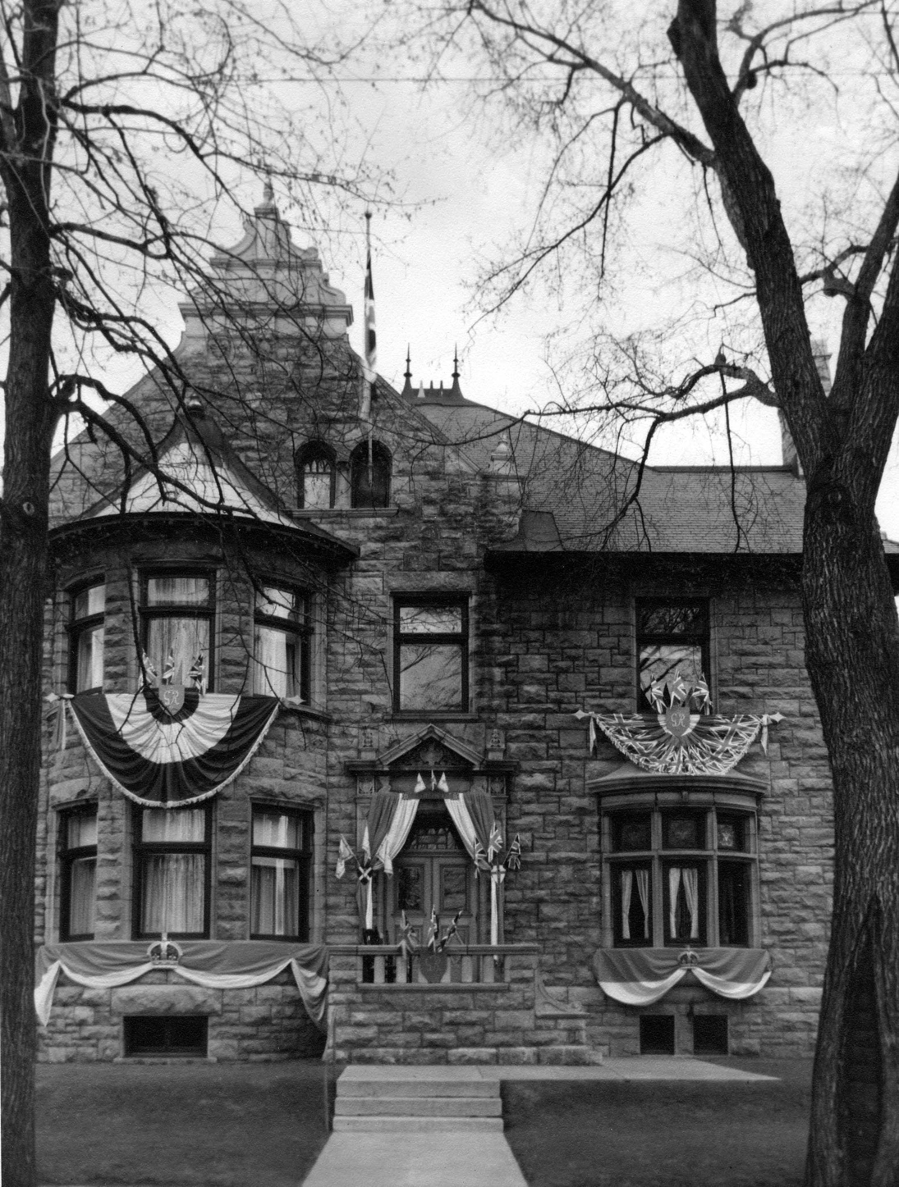

PHOTO ABOVE: The Holts’ house on Grande Allée, Quebec City, probably decorated for the royal visit in 1939.

As the Ukrainian crisis unfolded in 2022, the news reported on historic mansions around London owned by Russian oligarchs. One of these was the Victorian Athlone House, formerly Caen Wood House, located on Hampstead Lane in Highgate. In my research on the McIlwraiths, I had come across this building before. In 1912, John Holt of the Holt-Renfrew store at Quebec City and his wife Helen (Nellie) née McIlwraith were on a tour of Europe, using stopovers in Paris and London to cultivate their contacts in the garment and fur industries. At the time of their visit to Hampstead Lane, Caen Wood House was occupied by Thomas Frame Thomson and his family, and the Holts enjoyed tea and a walk through the grounds. The afternoon in these beautiful surroundings, “among the finest I’ve been in” as Helen confirmed in her travel diary, was a welcome respite from the recent terrible news of the sinking of the Titanic that had the Holts frantically buried in newspapers for days on end.

Born and educated in Scotland, Thomson was acclaimed for his role in developing South American, particularly Argentinian, transport facilities. Nellie does not expand on the connections between her family and Thomson, but there are at least two possible ones. Early in his career, he served as Resident Engineer of the Lanarkshire and Ayrshire Railway, and at a later stage one of many posts included that of Chairman of the Otis Steel Company in Cleveland, Ohio. The McIlwraiths came from Ayrshire and carefully nurtured their links with family and friends throughout Scotland. Indeed, rather than meeting in Canada, John and Helen appear to have fallen in love at an exhibition in Glasgow where his firm was showing furs and she was enjoying an extended visit with family. And in a second potential link, a group of businessmen from Painesville, Ohio, who were instrumental in founding the steel industry in Hamilton, included Will Child. His son Philip and Nellie’s nephew T.F. McIlwraith became friends at Hamilton’s Highfield School in the years before the outbreak of WWI, and a few years after the war T.F. married Will Child’s niece Beulah Gillet Knox. Sadly, the sinking of the Titanic was not the only catastrophe that the Holts came to associate with their visit in Europe: Thomson had only one more year to live when the Holts visited Caen Wood; at 46, he accidentally shot himself while extracting cartridges from a sporting gun.

One of the surprises of archival work is the way in which even individuals who in their own time were quite prominent can practically vanish from record, and although the Holt-Renfrew store remains a well-known institution in Canada, the Holts are a good example. Her nephew’s wartime letters indicate that Nellie generously shared her wealth with family members who needed support, but overall the Holts’ presence in the family papers is relatively slight. It includes several travel diaries, among them Nellie’s journal recording the trip to Europe during which they visited Caen Wood House. Two years earlier they had journeyed from San Francisco to Hawai’i, Japan, and China before taking the trans-Siberian express through Russia. They were a devoted and stylish couple, and their glamour was such that at Monaco, John was mistaken for the American financier J.P. Morgan, not to mention a Russian prince who temporarily made off with Holt’s dress trousers during a switch in hotel rooms. In contrast to his business partner George Richard Renfrew, John Holt – who died in 1915, not long after the trip to Europe – does not have his own entry in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, but the Weston Corporate Archives and the Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec were able to provide obituaries documenting the couple’s busy involvement in local charities, sports events, and civic celebrations. More recently, interest in Quebec’s patrimoine, including its tourism industry, has somewhat filled in the picture: members of the Facebook group Et si la ville de Québec nous était contée have posted vintage photographs of the Holt Zoo that existed from 1901 to 1932 near Montmorency Falls, and Gaétan Bélanger has published a book on the zoo (2020).

One of my favourite recollections as a researcher concerns a visit in the dead of winter to the Grand séminaire du Québec, with icy winds howling in from the St. Lawrence. I was working on my first book, Canadian Travellers in Europe, 1851-1900 (1987), and the archivist brought out diary after diary of travelling priests (who were often also pioneering scientists) for me to look at. Every so often, however, an item in the séminaire’s card catalogue had her produce a hand-wringing “Oui, nous l’avons – mais où?” In trying to reconstruct the lives of some of the individuals in Writing the Empire, I more than once sympathized with her exclamation.

With thanks to Professor T.F. McIlwraith for making the photo available.