March 2021

In January 1918, eighteen-year-old Thomas F. (“Tom”) McIlwraith from Hamilton, Ontario arrived in Britain for officer training, expecting deployment to the Western front later that year. Laden with packages and letters, he found his way to Rutland Lodge in the village of Petersham near Richmond. There he was welcomed by the “Hills-Phillips combination,” as he referred to them, specifically Hilda Phillips and her mother Evelina Hills. Both show up often in McIlwraith’s WWI letters, now held in the George Metcalf Archival Collection at the Canadian War Museum. They offered hospitality when McIlwraith was on furlough, received and forwarded his mail, and took him sightseeing around London, Kew Gardens, and Hampton Court.

It was clear from Tom’s letters home that there was a friendship of long standing between the Hills-Phillips families and the McIlwraiths, but it was less clear who the Hills-Phillipses were. Yet the mere fact that they occupied Rutland Lodge, a grand though freezing mansion with most its rooms shuttered, and that they employed a staff of eight in the middle of the war suggested that a closer look at them was in order. What was their connection to the McIlwraiths who were not affluent at all? As I relate in Writing the Empire: The McIlwraiths, 1853-1948 (University of Toronto Press, 2021), the networking of Tom’s family took them repeatedly beyond their middle-class world, socially and intellectually, and the following account illustrates the tight web of archival research that gradually clarified this particular association.

To begin with, McIlwraith’s brief reference to meeting Sir Lionel Phillips over lunch at Rutland Lodge sent me to biographies of Sir Lionel, a South African financier who made his money in diamond mining. He also escaped execution following his participation in the Jameson Raid in 1895-6, but by WWI he was thoroughly rehabilitated from this episode: he had been knighted and become chairman of the Central Mining and Investment Corporation in London as well as being “appointed a member of the Imperial Munitions Committee, which was concerned with the development of Britain’s mineral resources,” as Maryna Fraser writes in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Both of his sons were at the front, Harold in France and Frank at Salonica.

For the duration of the war, Lionel Phillips moved his entire family from Johannesburg to Britain where, together with his wife, the redoubtable Lady Florence, he worked energetically on behalf of the South African troops. They established a military hospital and clubs for officers and nurses near Richmond, and Tylney Hall, their estate in Hampshire, became an army hospital. As John Buchan in The History of the South African Forces in France (1920) and Thelma Gutsche in her biography of Florence Phillips (1966) have related, the Phillipses were so concerned to create a sense of home for the wounded that “corridors and rooms” were given South African names and Lady Florence even organized “a stuffed ostrich on wheels” for the Christmas festivities. Their son-in-law John Stuart Wortley, killed in action in 1918, leased Rutland Lodge in 1915. Mrs. Hills had left her husband Frank temporarily to his own resources in Hamilton and braved the dangerous crossing of the Atlantic to be with her daughter and her two young children. This is how McIlwraith came to visit the “Phillips-Hills combination” in Petersham.

This gave me a fair bit of information on the Phillipses but it did not tell me much about Hilda’s family or their connection with the McIlwraiths. Gutsche indicated that the Phillipses’ oldest son Harold had married Hilda Wildman Hills from Hamilton, Ontario, and an online genealogy suggested that her father, Frank Hills, was a “Justice of the Peace” there. As so often in the early days of my research for this book, my first port of call was the late Margaret Houghton, formidable local historian and archivist of the Hamilton Public Library, to whom it was news that Hills was a Justice of the Peace. Instead, she produced an obituary indicating that he had been superintendent of the Stephenson’s Children’s Home. This institution, also known as the National Children’s Home and Orphanage, housed immigrant children and coordinated their employment at Canadian farms and in households, and so represented a milieu quite different from that inhabited by wealthy entrepreneurs like Sir Lionel Phillips. Both Margaret Houghton and I were, however, for the time being stumped as to how Harold and Hilda could have met. A search of passenger lists indicated that Hilda had visited Britain and according to Gutsche Harold had attended Eton and Oxford, but that information alone did not establish contact between them, and they clearly did not move in the same circles.

The break came from a note located at the National Archives of South Africa in which Sir Lionel wrote to George Christie Creelman, president of the Ontario Agricultural College (OAC) at Guelph, about his son’s admission to the OAC, with Governor General Lord Grey – a man with extensive connections to South Africa – as reference. This information enabled the archivist at University of Guelph’s Archival and Special Collections to produce Harold’s OAC academic records between 1908 and 1912, along with details of the farmland he was to manage on his return to South Africa: a total of 12,000 acres in cattle ranching and citrus farming awaited him. There was also a reference to his marriage to Hilda, former student at the nearby Macdonald Institute. Founded by educator Adelaide Hoodless and tobacco industrialist Sir William Macdonald, the Institute was primarily intended to provide young rural women with solid training in home economics, but the program also attracted urban middle-class students. Because Macdonald students married OAC men with some frequency, the program was sometimes referred to as the “diamond ring course,” and Harold duly proposed to Hilda with a diamond ring purchased from Ryrie the Jeweler in Toronto, asking his father to forward the money for it.

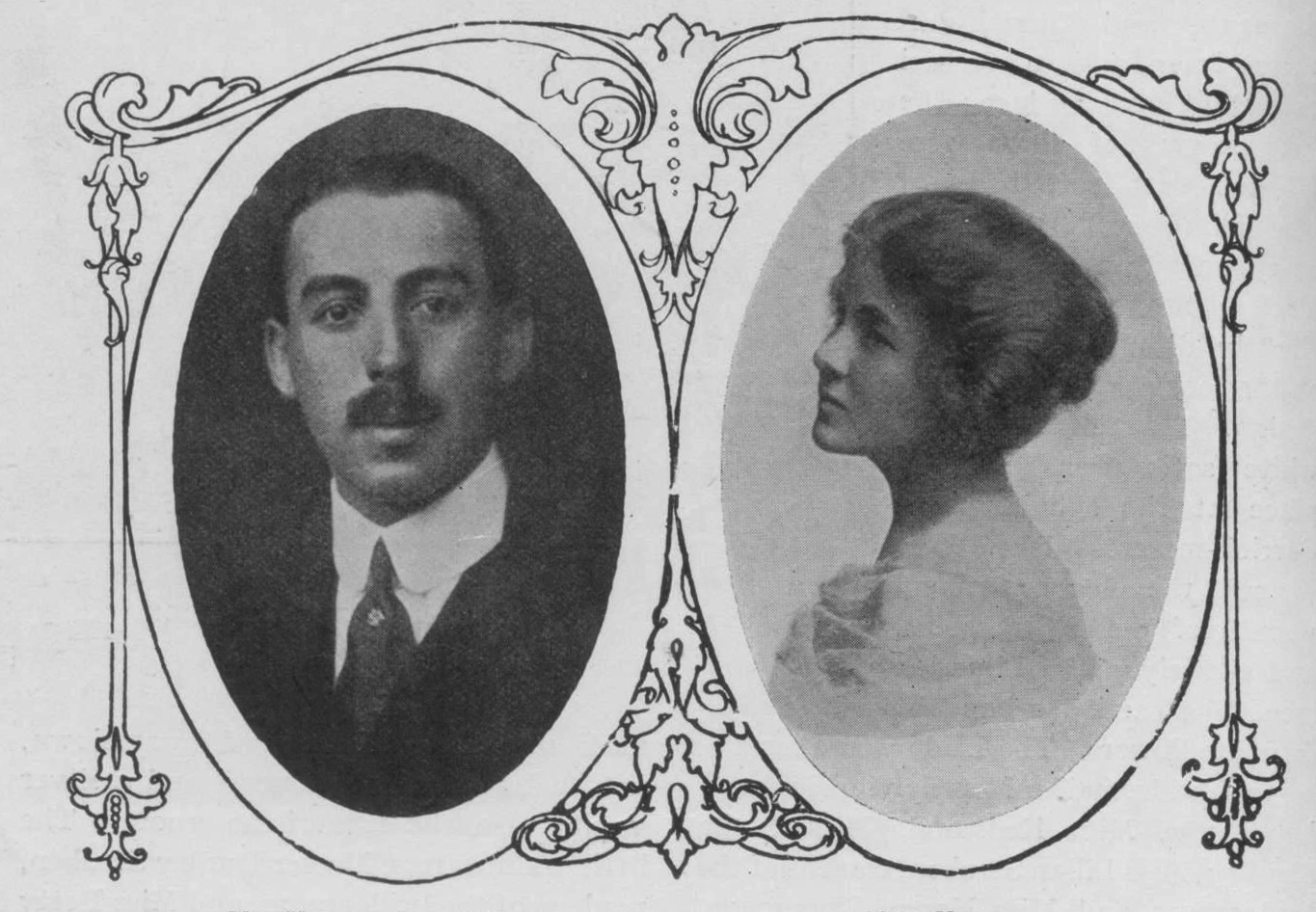

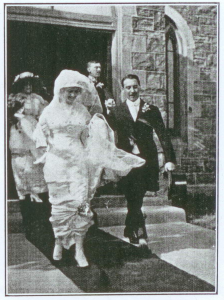

The reference to Hilda and Harold’s marriage in turn produced an article on their “Wedding of Wide-Spread Interest” which took place in Wentworth, Ontario in 1913. Tom McIlwraith’s sister Dorothy was one of the bridesmaids, decked out in a “large leghorn hat … in poke style with streamers of green,” as reported in the Hamilton Spectator, and earlier his mother had acted as a referee for Hilda’s admission to Macdonald. Harold’s parents were unable to come to Canada for the wedding, but the article took care to cite Sir Lionel’s involvement in the Jameson Raid and his various illustrious associations, literary and otherwise, including a reference in Gilbert Parker’s novel The Judgement House (1913). The Spectator forgot to mention that John Buchan’s Prester John (1910) was dedicated to Lionel Phillips.

But there was more. Gutsche’s biography of Lady Florence contained photos of Hilda’s husband and son but none of Hilda herself. My efforts to locate a portrait took me to the Johannesburg Art Gallery, the Johannesburg Public Library, the Johannesburg Heritage Foundation, Barloworld South Africa, ARTEFACTS (a website about the built environment of South Africa), the archivists of Balliol and Magdalen in Oxford, the authors of various books on the Phillipses, and finally to the descendants of Harold and Hilda in Britain, with generous help from all. These inquiries yielded among others a South African ladies’ magazine citing Hilda’s education at the Macdonald Institute as a special asset for a landowner’s wife, a stack of letters written by Harold from Guelph about his training at the OAC and his courtship with Hilda, and letters from the early days of their marriage at the Broederstroom Farm in Transvaal. There was also a pile of end-of-term reports from his earlier years at Eton that described his many shortcomings in terms of polished and eloquent rudeness and, together with the letters from Guelph, go some way toward explaining why his management of the farm as well as his and Hilda’s marriage were doomed to fail. At OAC, his favourite occupations were dancing, ice-skating and flirting but analyzing soil samples or looking after baby chicks bored him profoundly. Tom McIlwraith visited with the Hills-Phillipses in Petersham at a time when, ironically, Harold’s long absences at the front temporarily improved the couple’s relations.

As I hope to have shown, I have reason to be very grateful for archivists’ knowledgeable and gracious assistance, including the staff at the University of Guelph’s Special and Archival Collections. Their help was essential in the success of this intricate search.

With thanks to Sarah Welham (Research Centre, Johannesburg Heritage Foundation) and Essie Chaphie (Johannesburg Reference Collection) for providing information on and scans from the S.A. Ladies Pictorial.