Written for Special Collections, Fogler Library, University of Maine

June 2021 (Revised May 2022)

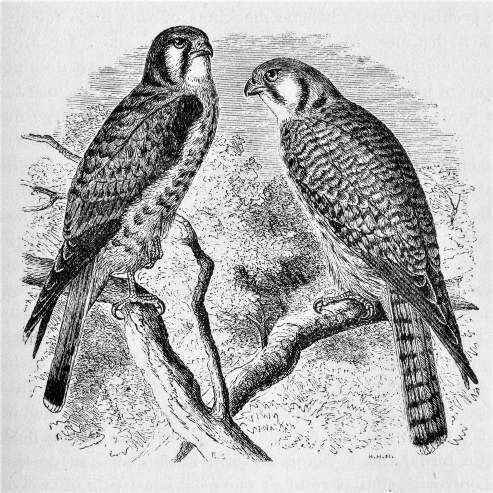

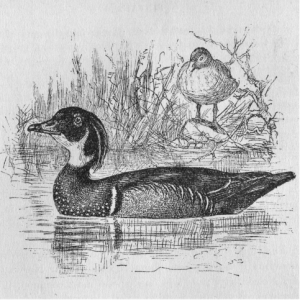

Thomas McIlwraith (1824-1903) was known throughout North America as an important ornithologist of his time. Cabinet-maker, manager of gas works and coal dealer, his true passion was the birds. His book, The Birds of Ontario, went through two editions (1886, 1894), and he was one of only three Canadian founding members of the American Ornithologists’ Union.

Self-taught, McIlwraith communicated with professionals like Joel Asaph Allen, William Brewster, Joseph Grinnell and Robert Ridgway, and when it came to preparing for publication or dealing with critical reviews of his publications, he could rely on being mentored by them. A collection of postcards exchanged with these scientists, as well as birdwatchers, taxidermists and dealers in guns, has been deposited in the archives of the Hamilton Public Library (HPL), and his youngest son’s logbook describing several years of bird watching with his father is held at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto. A typescript of The Birds of Ontario (2nd edition), with annotations possibly inserted by his daughter Jean who edited the book for him, also survives at the HPL. As a trained musician and a writer, she may be responsible for the strong emphasis on music and literature in the second edition. This feature, however, appears to have been vetoed by botanist John Macoun when he and McIlwraith were planning a collaborative work on the birds of Canada that remained unfortunately unpublished. Macoun considered the musical and literary allusions unscientific – or so we must extrapolate in the current absence of Macoun’s letterbooks.

In turn, Thomas McIlwraith’s ornithological network provided important contacts for his daughter when she was looking for work after her mother’s death in 1901. Among the correspondents in the HPL postcard collection is Manly Hardy, a trapper and naturalist from Brewer, Maine, whose daughter Fanny (also spelled “Fannie”) became a well-known naturalist herself as well as an expert on regional folklore. In her book Fannie Hardy Eckstorm and her Quest for Local Knowledge, 1865-1946 (2013), Pauleena M. MacDougall describes the collaboration between father and daughter along with Eckstorm’s own studies and, in doing so, offers a corrective to an understanding of such work as entirely dominated by male researchers. In a series of letters exchanged between 1901 and 1902, Eckstorm agreed to act as “godmother” to Jean McIlwraith when her mother’s death and her father’s increasing debility left her in a precarious emotional and financial situation. Eckstorm was particularly sympathetic because, in quick succession, she had herself just lost her husband and young daughter.

To the researcher, the internet can be an exhilarating and infuriating place to be. At times unexpected yet crucial information is tossed up casually on the first try, at others the web produces, straight-faced, data such as genealogies that turn out to have less to do with actuality than wishful thinking. In this case, the letters between Eckstorm and McIlwraith were located through the Nineteenth Century Index database, a reputable source to be sure but also one curiously selective in its listings of manuscript collections. I was however doubly fortunate because Desirée Butterfield-Nagy, the archivist at the University of Maine, turned out to be a prompt and knowledgeable guide in navigating the archive which arrived almost at once in a gratifyingly substantial collection of scans.

Their initial connection through their fathers’ ornithological studies is threaded throughout the letters, with Jean collecting letters of introduction to “bird people” in New York’s publishing business and Fannie proposing that she meet her brother, an illustrator of naturalist works also working in New York. But their discussions were much broader, allowing Jean (who came from an emotionally reticent family) to pour out her troubled thoughts to her friend. They disagreed over her future place of work because, unlike Eckstorm who had enjoyed working for a publisher there, Jean disliked Boston as an “intellectual snob-centre.” Instead, she was attracted to the bohemianism of New York and reported with exhilaration on her first few weeks of independence. She was instantly surrounded by female friends, many of them musicians and writers though there were also a mathematician, a theosophist, and a nurse, some already working in New York and others flocking to the city for a visit. One of her friends steadfastly accompanied her on her rounds to all the important publishers until work had been lined up.

A brief diary McIlwraith kept of her early days in New York remains in family possession, and some of it made its way verbatim into her letters. The exuberance of her correspondence with Eckstorm is a valuable antidote to the disillusionment that overcame her in later years, and it is a happy coincidence that this exchange has been preserved.

A full finding aid for the Fannie Hardy Eckstorm collection is available from the Fogler Library. For Jean McIlwraith’s letters, see p. 22:

https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1183&context=findingaids

Acknowledgement: With thanks to Professor T.F. McIlwraith for providing scans of illustrations from The Birds of Ontario.