Prompt: Each student will be assigned a section of the novel Green Grass Running Water (pages will be divided by the number of students). The task at hand is to first discover as many allusions as you can to historical references (people and events), literary references (characters and authors), mythical references (symbols and metaphors).

In my first blog, I said, “I expect that naming will become important [in relation to this course], as names have different associations, meanings, and symbolic value to different peoples”; and that is something King really hits on in GGRW.

I was assigned the section from when “Lionel pulled his foot out of the puddle” (121), to when Bursum says, ” That’s right” (129). Or, in other words, from when Lionel sees the Indians for the first time, to when Bursum shows Minnie The Map.

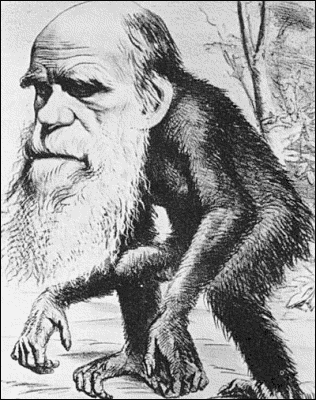

The four old Indians–Lone Ranger, Ishmael, Robinson Crusoe, and Hawkeye–are called by names of famous Western fictional figures, which may vaguely, in a satirical way, sound ‘Indian’; but their ‘real’ names according to Dr. Hovaugh’s file are Mr. Red, Mr. White, Mr. Black, and Mr. Blue, which correspond with The Medicine Wheel (Paterson 3.2), but may also be references to the film Resevoir Dogs (Flick 148). As you can see, King is already drawing connections, including one between the seemingly arbitrary names, or colour codes, of the four Indians, and the seemingly arbitrary lines drawn on a map.

I think this section is the beginning part of creating a parallel between the four old Indians, and The Map; one that shows them being introduced in the beginning of back to back segments–to Lionel and Minnie respectively.

Lionel first notices “the Indian with the mask,” and then “the Indian in the Hawaiian shirt with the red palm trees” (121). The mask is that of the Lone Ranger, who is based a hero in western books, radio serials, and movies that brings along a faithful Indian companion named Tonto. The character of Tonto is often seen as degrading to Native Americans, as he speaks in broken English, and while the writers claim his name means ‘wild one’ in Potowatomi, it definitely means ‘stupid’ in Spanish, so the name was changed to Toro (meaning ‘bull’) or Ponto for Spanish audiences. As King puts it, “That’s a stupid name” (71). Interestingly, Kemosabe–the name Tonto gives his boss–also has controversy surrounding it, with theories ranging from ‘white man’ to ‘a horse’s rear end.’

On the other hand, the Hawaiian shirt with the palm trees is a reference to the desert island Robinson Crusoe is stranded on. Robinson Crusoe is the eponymous character of Daniel Defoe’s most famous novel, and in it’s first edition, it was credited to him–leading many to believe he was a real person. However, he is based on the true story of Alexander Selkirk. Aided most of all by the Bible giving him spiritual strength needed to survive, he is also helped by Man Friday, a “savage” he saves from cannibals, and then converts to Christianity.

I think you’re seeing a pattern here. The original Lone Ranger, Robinson Crusoe, Ishmael, and Hawkeye all had “noble savages” as companions. Hawkeye had Chingachgook–an Indian converted to Christinity–and Ishmael had Queequeg–who’s coffin serves as his flotation device when the whale Moby Dick destroys the Pequod (Flick 141-43).

By making Hawkeye, Ishmael, Lone Ranger, and Robinson Crusoe (non-Christian) Indians, King is “fixing” the worldview of the novel in the same way they want to–step by step.

“Start small and work your way up” (125).

Immediately following Lionel asking, “So [haha], where are you going to start?” we see Bill Bursum.

Bursum is based on two men famous for being hostile to Indians. Holm O. Bursum (1867-1953) was a senator who proposed the infamous 1922 Bursum Bill, which allowed any non-Indians to retain land they squatted on prior to 1902, at the expense of Pueblos in the area of New Mexico. Bursum Bill; Bill Bursum – get it? King takes that further by also connecting Bursum’s nickname Buffalo Bill to William F. Cody (1846-1917), whose Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show exploited Indians for entertainment (Flick 148). FYI, this is also the inspiration for Jame Gumb’s alias in Silence of the Lambs.

Bill Bursum’s Map has a connection to Fort Marian ledger art. According to Margary Fee, they represent different concepts of maps taken from different cultures, and since maps are a form of writing, that dismantles the distinction between orality and literacy (10). She says that while “The ledger art records the Plains Indians’ use of a horse as a military technology as well as the foundation for a whole way of life… Bursum’s map symbolizes the connections between television, advertising, media and conquest, and a way of life built on communications technology” (10). Therefore, it is telling that all of the westerns playing on the television screens assorted to look like a map of Canada and the United States end with the Cowboys winning and the Indians losing; and all of the stories told by Lone Ranger, Ishmael, Robinson Crusoe, and Hawkeye end with a Woman being sent to Fort Marion.

On judging his masterpiece, Bursum says, “It has no value. It is beyond value,” no doubt evoking “It’s priceless” from Mastercard ads (128). Then, he name drops The Prince by Machiavelli, saying “It’s all about advertising. If you’re going to succeed in this business, you better read it” (128). It’s clear that he likes its central axiom: “Power and control” (128).

Perhaps most tellingly, in response to Minnie saying, “I suppose its advertising value compensates for its lack of subtlety,” he says, “That’s right. It’s like being in church. Or at the movies” (129).

Works Cited:

Adams, Cecil. “In the old Lone Ranger series, what did ‘kemosabe’ mean?” The Straight Dope. 18 July 1997. Web. 10 July 2015.

Fee, Margary. “Introduction.” Canadian Literature 161/162 (1999): 9-11. Web. 3 July 2015.

Flick, Jane. “Reading Notes for Thomas King’s Green Grass Running Water.” Canadian Literature 161/162 (1999): 140-172. Web. 3 July 2015.

Franey, Evan. “Introduction.” Liminal Space between Story and Literature. UBC Blogs, 15 May 2015. Web. 10 July 2015.

Johnson, Carla. “The Bursum Bill.” History Blog. 6 Mar. 2011. Web. 10 July 2015.

Paterson, Erika. “Lesson 3.2.” ENGL 470A: Canadian Studies. UBC Blogs, May 2015. Web. 3 July 2015.

“Keeping History: Plains Indian Ledger Drawings.” American History. Smithsonian Institute, 2009. Web. 10 July 2015.

“Robinson Crusoe 1719 1st edition [image].” Wikipedia. 28 Jan. 2006. Web. 10 July 2015.

“The Prince.” Cliff’s Notes. N.d. Web. 10 July 2015.

“Tonto: Stupid or Wild One?” Truncated thoughts. 14 Aug. 2011. Web. 10 July 2015.

“Two Extraordinary Travellers.” BBC. BBC, 19 Sept. 2014. Web. 10 July 2015.